I am delighted to have a chance to bring you up to speed on an event that I was privileged to attend in July, the first ever ‘International Religious Freedom Summit’. There are times when an event is so significant that even the news media misses it! Or, as is more often the case, the coverage turns the event round to make a political point or prod a national debate. For all sorts of (what I would see as) entirely predictable ‘political’ reasons, there was little in our local Washington papers about the International Religious Freedom Summit earlier this year; despite the fact that it was the first of its kind and, crucially, planned and guided not by political elites or religious institutions, but by a broadly representative body of global citizens, who were (and are) concerned about, or just generally interested in, the broad field of ‘religious freedom’. It was a good event in every sense: refreshing, stimulating, and provoking in equal measure. Here was a forum to address the ‘soul’ of the world and the way we are, or more often, are not, safeguarding and nurturing that ‘soul’ in one another and in the families, workplaces, and communities of which we are a part – let alone, in those places of cultural and political power and influence that shape our lives without our necessarily wanting it or recognizing it. Of course, for some, religion represents and perpetuates all that’s wrong with the world: the July Summit was a good reminder not only of the good religion can do, but also of its foundational place in building and sustaining a healthy planet with mutually respectful residents.

Events like the Religious Freedom Summit do not just happen. They need to be carefully planned and responsibly funded. With 1,200+ participants from 30+ countries, representing 80+ religious and civil society organisations, the Summit was palpably not just another conference. Central to its style and success was its deliberately inclusive theme, ‘Religious Freedom for Everyone, Everywhere, All the time’. In other words, the aim of the conference was not to celebrate, or complain about, one particular religion, but to consider the place ‘religion’, and specifically ‘religious freedom’, fares in the world in the third decade of the 21st century. Was the conference a success? I certainly think so. It gathered representatives from around the world to share their experience of faith and their common commitment to celebrate religion’s place as an instrument of good to be honoured by all. Unlike meetings on ‘religious freedom’ convened by governments or law societies, the July Summit in DC was planned and hosted by civil society organizations and faith-based enterprises from around the world. This gave it a freedom to ask awkward questions of policy and policy makers, of international law and domestic lawmakers. As a retired judge, I attended as a Senior Associate of Oxford House and as a Board member of the DC-based Institute for Global Engagement.

(Former chair of the US Commission on International Religious Freedom [USCIRF])

The co-chairs of the Religious Freedom Summit were former US Ambassador for Religious Freedom, Hon. Sam Brownback (b. 1956; Amb. 2018-2021) and Katrina Lantos Swett (b. 1955), President of the Lantos Foundation: two people who in their different ways have worked hard over the years to ensure ‘religious freedom’ is discussed and protected in a thoughtful, clear, and generous way. To diffuse any sense that the event was biased towards American or Christian interests, the co-chairs made unequivocally clear during the conference that to them, ‘[F]reedom of religion, is a fundamental human right … [and] foundational to everything and every other human and civil right’. In other words, the issue under discussion was not so much ‘religious freedom’ as human identity. Not all at the conference accepted the historical resonances and ‘religiosity’ of the chairs’ vision, but the conference’s explicitly ‘inclusive’ terms of reference ensured that the relation between a person’s ‘right to a religion’ and the larger issue of their rights ‘as a human’, remained central. It was important to see the ‘right to (a) religion’ set in this wider context of ‘human rights’ generally.

As indicated, not everyone at the conference shared the historical and theological principle that ‘religious freedom’ is foundational for all human rights and, indeed, what it means to be human. However, some presenters were keen to draw attention to the prominent role accorded religion in the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution (15 December 1791), where, it was pointed out, religious freedom was established as the first freedom and ‘right’ of America’s new citizens. This principle, it was argued, expounds the position on human freedom that was and is articulated in the U.S. Declaration of Independence (4 July 1776), where we find: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.’ If America sometimes struggles to understand the application of this principle today, others attending the conference were encouraged to discover the foundational nature of freedom and of religion in America from its conceptual and legal inception.

While some speakers drew on the U.S. Constitution to ground discussion of religious freedom, others appealed to the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Approved by the General Assembly of the new United Nations in December 1948, the Declaration expressed common standards for all people, and, for the first time, presented a set of ‘fundamental rights’ that should be protected by the rule of law around the world. UDHR contains 30 Articles which identify the specific ‘rights’ covered by the Declaration. The oft-quoted Article 18 is clear: ‘Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion, this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom to either alone or in community with others and in public or in private, to maintain his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.’ Presenters at the Summit found here grounds to defend ‘religion’ when society at large may question its validity or challenge its assumptions.

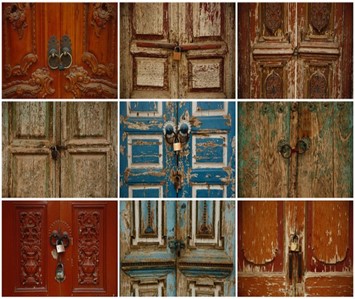

Both implicitly and explicitly UDHR’s ‘Preamble’ sets freedom of speech and belief alongside freedom from fear and want as consistent with, and reflective of, the highest ‘aspirations of the common people’. The problem with this, as the conference revealed, is that over time a perceived ‘human right’ – and with that, what we might think of as a necessary feature of being human – can be too easily detached from, or determined by, the undefined (and, it seems, often changing) ‘aspirations of the common people’. In other words, the long-term consequences of this (now terminologically dated) definitional link, has been, as some speakers at the conference urged, the relegation of religious freedom from its pivotal role in defining and preserving what it means to be human. In other words, the UN’s Declaration of Human Rights, though serviceable once, is – or, perhaps more optimistically may be – no longer ‘fit for purpose’ as a safe stronghold for religious freedom and bastion against the erosion of human identity.

The Summit in July tracked the recent history of America’s own struggle to define and defend the Constitutional principle of ‘religious freedom’. Reference was made to the International Religious Freedom Act (IFRA), which Congress passed in 1998. The law, as later amended, aimed to raise the profile of religious freedom in U.S. foreign policy so that it conformed to the vision of the Founding Fathers in the Constitution and the UDHR. The 1998 law sought to safeguard the principle of ‘religious freedom’ by appeal to the U.S. Constitution and to International Law. In other words, Congress defended the principle that a person anywhere in the world has a right to follow their conscience and to believe or not believe, and to live out that belief openly, peacefully, and without fear of threat, restraint, or reprisal. The international instruments that IFRA drew on to justify this claim were not only UDHR but also ‘The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights’ (ICCPR: adopted 16 December 1966, enforced 23 March 1976), the ‘Helsinki Accords’ on Security and Cooperation in Europe (1 August 1975), and the ‘Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Intolerance and Discrimination Based on Religion or Belief’ (25 November 1981). In May 1997, Virginia Congressman Frank Wolf (b. 1939) and Pennsylvania Senator Arlen Foster (1930-2012) presented a bill (H.R 2431) ‘The Freedom from Religious Persecution Act’. This bill failed to secure approval in the Senate. However, in March 1998, Senator Don Nickles (b. 1948) introduced a new International Religious Freedom Act, which was technically an amendment (or substitute) to H.R. 2431 but in fact reproduced it in its entirety. This bill was passed by the Senate and Congress on 8 and 10 October 1998 respectively. In 2016, in recognition of his central role throughout, a revised ‘Frank R. Wolf International Religious Freedom Act [H.R. 1150]’ was passed which amends IRFA 1998 ‘to state in the congressional findings that the freedom of thought and religion is understood to protect theistic and non-theistic beliefs as well as the right not to profess or practice any religion’. U.S. law has, as here, rightly kept pace with societal change.

In the protracted – and often heated – debates in the U.S. over ‘religious freedom’ an important distinction has emerged, which the July Summit was quick to register; namely, between ‘freedom of belief’ and ‘freedom of conscience’. For, though a state may notionally accept religious diversity and practice (at times, in contradiction of a state religion), it may simultaneously deny a free exercise of conscience to express that religion or belief openly and publicly. Articulate defenders of ‘religious freedom’ per se are in the forefront of protesting against this lax bifurcation of word/law and deed/behaviour. Defenders of ‘religious freedom’ have much to do. As the Summit was reminded by quite a number of the speakers, countless millions around the world do not have freedom to express their religious faith openly and publicly. The Pew Research organization reports ca. 80% of people worldwide live under some kinds of restriction on their religious (and civil) liberties. For their part, religious adherents are often in the forefront of voicing opposition to oppressive regimes and protesting de-humanizing behaviour.

In light of the plight of many adherents of religion worldwide, the Summit gave considerable time to reports of persecution because of an individual or community’s religious identity. Instances of official (local or national) opposition to public worship and private religious beliefs – regardless of the specific religious tradition they reflected – were profiled for delegates at the conference. Shared stories across faith divisions created a basis for greater mutual respect. Reports of extraterritorial persecution by a repressive government of expatriate citizens for ‘blasphemy’, of imprisonment, torture and genocide of religious ‘minorities’, of the imposition of cultural and ideological conformity by a dominant ‘majority’, of economic and educational marginalization of religious communities when their faith was seen as unpatriotic or divergent, all contributed to the Summit’s contribution to telling a story the world (and the world’s media) needs to hear.

What struck me personally was the threat religion poses to authoritative regimes. Repression of ‘religious freedom’ is, it seems, often born of socio-political fear or a desperate need to control. Stories of ideological ‘retraining’ in what are effectively ‘concentration camps’ smacks of the old days of Communist conformism. Detention without trial, or simply on the basis of a neighbour’s accusation or the shape and/or colour of a person’s skin, do not reflect humanist ideals nor the Judeo-Christian valuation of every individual as ‘made in God’s image’. They are also fail to reflect the palpably sensible, ‘inclusive’ ideals that are enshrined in the U.S. Constitution, and in globally accredited legal instruments that uphold human freedom and personal identity.

Two more things, as I end. First, like the work of the Institute for Global Engagement, the Summit provided a space where the issue of ‘religious freedom’ could be safely and openly discussed: as the IGE defines its purpose, ‘to catalyze freedom of faith worldwide so that everyone has the ability to live what they believe’. Only in such safe places can truth be spoken to power and influence brought to bear on policies and policymakers who determine the life and freedoms of countless millions.

Second, the issue of ‘religious freedom’ is not going to go away. Faith has its own inner energy. It is not just that the blood of martyrs inspires sacrifice, but at the heart of religion is a commitment to something, or somebody, that matters more than the immediate, that offers hope and purpose beyond the comfortable and convenient. As long as these realities drive religious sensitivities, the longing for a social space and place to enjoy their free expression will remain. Secularists and politicians be warned!

Hon. Rollin van Broekhoven, Senior Associate