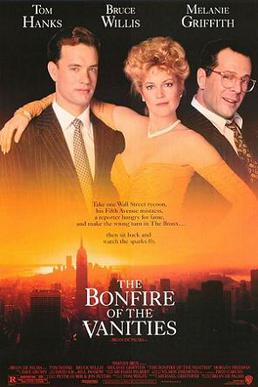

When it was released in 1990, critics panned Brian de Palma’s (b. 1940) film adaptation of Tom Wolfe’s novel The Bonfire of the Vanities (1987). The public agreed. Despite its best-selling literary source, satirical humour, and star-studded cast (including Tom Hanks, Bruce Willis, Melanie Griffith, Kim Cattrall and Morgan Freeman), the film was a commercial flop, grossing $15m. against a budget of $47m. It’s not the first time – and will certainly not be the last – a good book has made a bad film. Images can be a poor substitute for imagination. But can we – or, better, should we – read more in the public’s reaction? I suggest we might.

It’s sad – at times, embarrassing – when what is meant as a celebration becomes the opposite; a portrait rejected by the sitter, a meal for friends under-cooked, a Christmas gift despised, a good book spoiled by a poor film. Wolfe’s (originally serialized) novel is set in 1980s New York City. It is a tough study of what it means for the three main characters – WASP bond trader Sherman McCoy, Jewish Assistant District Attorney Larry Kramer, and the expatriate British journalist Peter Fallow – to be consumed by the modern ‘vanities’ of ambition, class, greed, politics and race. ‘Vanities’, that is, as the empty mirage/s of life the Old Testament ‘Preacher’ denounces at the start of Ecclesiastes (Hebrew: Kohelet): ‘Vanity, all is vanity’ (1.2), a futile vapor without substance or meaning.

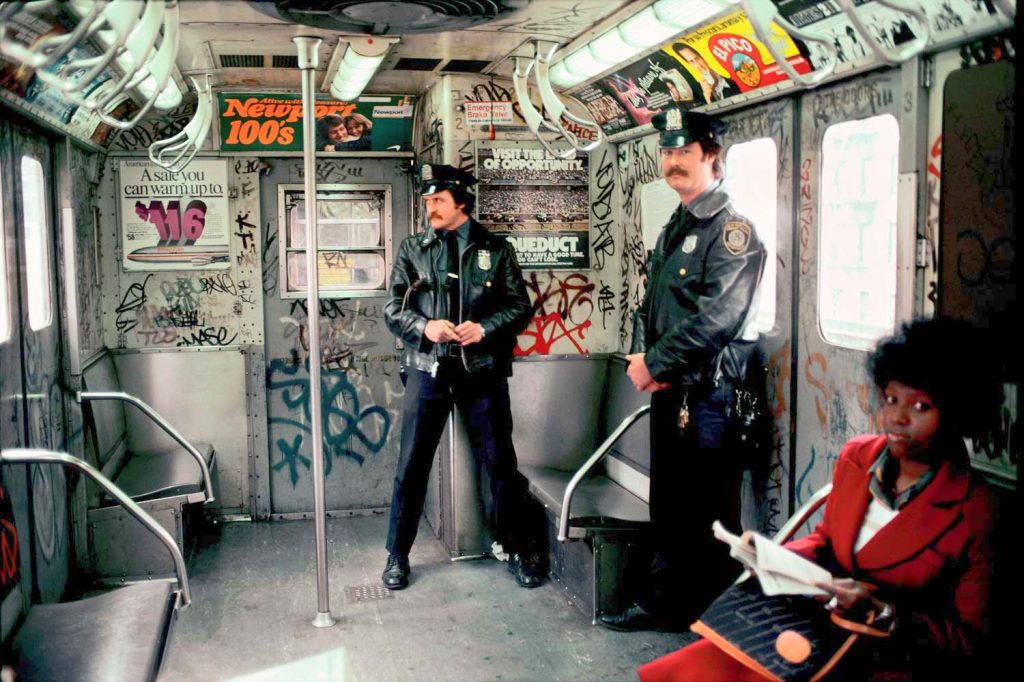

Like many edgy postmodern works, Wolfe’s book is rooted in history and reality. Despite the socio-economic scarring of cities by COVID, Brazilian cinematic storyteller Lucas Compan’s observation (in 2017) of New York in the 1980s, is still true. It was, he wrote, ‘an altogether different city from the safe, clean (for the most part), cosmopolitan urban playground it is today. Homicides were at near record highs, the Crack epidemic was raging’, and the city ‘had not yet experienced the wave of gentrification that has marked it in modern times’ (www.greatfuturestories.com). The book and film version of The Bonfire of the Vanities are both set in this city, wracked by cultural and racial tension, by power, greed and ambition. The widely reported murders in white neighbourhoods of Willie Turks in 1982 and Michael Griffith in 1986, and the lauding of commuter Bernhard Goetz in 1984 for shooting at black youths who tried to rob him on the subway, give form and substance to Wolfe’s dark, socio-political narrative. So, brusque, no-nonsense District Attorney (later Chief Administrative Judge for the New York Supreme Court) Burton B. Roberts (1922-2010) is the model for Wolfe’s character Myron Kovitsky. Fiction, as de Palma’s film confirms, can be a poor, and inaccurate, commentary on reality – but, as ancient wisdom urges, what we take to be ‘reality’ may not be: it may be just ‘vanity’.

Wolfe’s book has deeper historical roots than 1980s New York. ‘The bonfire of the vanities’ (Italian: falò delle vanità) was an event – or, more accurately, a series of events – in late-Medieval Europe. During his lifetime, the Franciscan friar, earthy popular preacher, and scholastic economist, Bernardino of Siena (1380-1444), the so-called ‘Apostle of Italy’, used simple images in powerful homilies to attack a raft of social evils, including. sorcery, gambling, sexual misconduct, infanticide and usury. ‘Bonfires of vanities’ were held across Italy when Bernardino preached. Crowds gathered at dawn to hear him, and then threw their ‘vanities’ into vast conflagrations. Mirrors, high-heeled shoes, cards, dice, perfume and wigs, were all consigned to the flames, while Bernardino exhorted his listeners to live pious lives and not to swear, gamble, commit adultery or tell lewd jokes. More famously, on ‘Shrove Tuesday’ (7 February) 1497, the eve of the Church’s 40-day penitential season before Easter, the passionate and puritanical Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola (1452-1498), and his youthful followers, built a huge bonfire in the public square in Florence and burned a pile of artefacts they considered spiritually and morally corrosive. According to a firsthand account by the Florentine historian Francesco Guicciardini (1483-1540), the focus of this dramatic gesture was anything and everything that could lure a person away from God and towards life’s ‘vanity’ and ‘vanities’. Mirrors, cosmetics, and dresses all went up in flames; so, too, fine art and sculpture, musical instruments and books, poems and scores.

This medieval ‘Bonfire of the Vanities’ remains controversial. Lest Savonarola be too rapidly dismissed as a cultural barbarian and anti-social killjoy, we should remember that he already had an established reputation as a respected pastor and prophet of Florence’s future glory. This earned him the right, in the eyes of many, to be the architect of his city’s spiritual and moral renewal. But who cannot in some measure grieve the (reported) loss of art works by Boccaccio (1313-1375) and Fra Bartolomeo (1472-1517), by Leonardo da Vinci’s (1452-1519) fellow-student Lorenzo di Credi (1456/59-1537) and Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510), who, according to some historians (including the scientific and literary polymath Giorgio Vasari [1511-1574]), destroyed many of his own works when he came under Savonarola’s hardline influence? A ‘bonfire of vanities’? – to many people, absolutely not! Just another spiteful desecration of human culture and creativity, of life’s beauties and realities.

Oh, really? Others have read, and reacted to, this historic event quite differently.

Tom Wolfe and Brian de Palma aren’t the only artists to have been stirred by the medieval cult of burning the objects of insatiable human desire to underscore their fading value and allure, to say nothing of their caustic immorality. The ground-breaking Victorian novelist George Eliot (aka Mary Ann Evans, 1819-1881) set her fourth novel, Romola (1863), amid the grandeur and chaos of the Florentine Republic in the late-15th century. Florence, and the female protagonist Romola, are now interpreted by many scholars as tropes for Eliot herself and the Victorian society she inhabited: the former locked in a lifelong struggle with popular shibboleths, the latter rocked by new perspectives from science, philosophy and theology. As the American scholar Felicia Bonaparte has written, ‘Philosophically confused, morally uncertain, and culturally uprooted, [Florence] was a prototype of the upheaval of nineteenth-century England’ (q. P. Nestor 2002, 92). So, the life and times of Savonarola become a backcloth for the enlightened Romola (qua Eliot) to reexamine the (religious) dilemmas and (characteristic) duties of a thoughtful woman in turbulent times. The Victorian journalist Richard Hutton (1826-1897) called Romola ‘one of the greatest works of modern fiction’ and ‘probably the author’s greatest work’ (Spectator, 1863). To Eliot, ‘every sentence’ was ‘written with my best blood’ and with ‘the most ardent care for veracity of which my nature is capable’ (Selections, 1985, 481). Eliot visited Florence a number of times over an eighteen-month period to research and write Romola. This story, she clearly believed, deserved her best efforts. We should, perhaps, take note.

The ‘Bonfire of the Vanities’ that Girolamo Savonarola’s preaching inspired is one of the historical events Eliot relates in Romola. Set between the death of Lorenzo de’ Medici (1449-1492), head of the Medici clan, de facto ruler of the Florentine Republic, and famed banker, diplomat, and patron of the arts (including of Botticelli and Michelangelo [1475-1564]), and Romola’s final return to Florence after Savonarola’s trial and execution (23 May 1498). In the interim, we find Romola wooed by the (ultimately treacherous) young scholar Tito, caught up in the capitulation of Florence to French forces, and drawn to the integrity and humanity of Savonarola as he cares for the sick and suffering in a war-torn city and Republic. Though to some – not least the papacy of his day – Savonarola is an object of mockery, fear and suspicion, not to Eliot. In keeping with her religious iconoclasm, and urgent calls for authentic sympathy and sacrifice in mid-Victorian society, she, like Romola, finds in him a consistent integrity and love for humanity that outshines Tito’s unreliability, the city father’s dirty political machinations and the papacy’s fear-filled venom. In short, Eliot’s novel is her own ‘bonfire of the vanities’ onto which Victorian cant, prejudice and judgementalism, are cast. For his decisive calls for Church renewal, religious freedom, and an end to clerical corruption, despotism and the exploitation of the poor, Savonarola acquired many enemies. To Eliot, many of the 16th-century Protestant Reformers, and an equal number of religious fanatics and social critics ever since, he asked and asks probing questions of the besetting ‘vanities’ that consume societies. But, as we see perhaps in the public’s reaction to de Palma’s version of Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities, mirrors held up to a society are apt to be cast into the cultural flames of public animosity and denial. Few of us want to see, on reflection, that our ‘vanities’ are indeed ‘vanities’, futile vapors without substance of meaning.

The image of treasures consumed in flames, of popular ‘values’ devalued when considered, of iconoclasts confronting popular prejudice, of sacrifices made for a shared humanity, are recurrent themes in literature after George Eliot. So, echoes of the medieval ‘bonfires of the vanities’ are heard in modern sources as varied as E.R. Eddison’s Anglo-Italian fantasy novel A Fish Dinner in Memison (1941), the second in his epic Zimiamvian Trilogy; Irving Stone’s powerful biography of Michelangelo, The Agony and the Ecstasy (1961); Chelsea Quinn Yarbro’s The Palace (1978), set like Romola in late-15th-century Florence; Michael Ondaatje’s The English Patient (1992), a Man Booker Prize winning study of love, sacrifice and betrayal in war-torn Italy; the sixth installment of Anne Rice’s, ‘Vampire Chronicles’, The Vampire Armand (1998), which tracks an eternally young soul (with the face of a Botticelli angel) across continents and centuries in search of peace and immortality; Timothy Findley’sslow-moving study of mortality and mental illness, Pilgrim (1999); Ian Caldwell and Dustin Thomason’s The Rule of Four (2004), based on a group of Princeton students gripped by the idea that the late-15th-century Italian text Hypnerotomachia Poliphili contains clues to the whereabouts of works by the Dominican Friar Francesco Colonna (1433/4-1527) secreted away from Savonarola’s ‘bonfire of the vanities’; Traci L. Slatton’s The Botticelli Affair (2013), that reflects her love of dark fantasy and lost fine art; and Jodi Taylor’s, No Time Like the Past (2015), in her Chronicles of St Mary’s Institute of Historical Research series, that makes past history present in disconcerting ways. Savonarola is also prominent in Jordan Tannahill’s play Botticelli in the Fire (2016), in the TV series The Borgias and Medici,and even in the video game Assassin’s Creed! But few are as brave, clear-headed, and well-informed as Eliot (and, perhaps, Tom Wolfe), in crafting for our own turbulent, prejudiced, secular age, a story in which ‘priceless gems’ and cultural ‘masterpieces’ that the public values, or the prevailing standards of political, diplomatic, and corporate ‘success’ – let alone what fashionistas market as essential aids to modern beauty – are consigned to the white flames of proportion, ‘reality’, morality and integrity. No, those who would dare to write about such risk the fate of de Palma’s film, being panned without recourse.

So, what’s the take-away from Eliot, Savonarola, and Wolfe and de Palma’s The Bonfire of the Vanities? Come back to the strap line of this Briefing, ‘on fashion, folly and the futility of war’.

First, on fashion. In a 2019 report, McKinsey valued the global fashion industry at $2.5tr (nearly 2% of the world’s GDP): this headline figure is projected to grow by 3.9% to 2025 (despite a 25-30% contraction in the market in 2020). On the eve of the pandemic, spending on clothing in the UK reached an all-time high of ₤61.2bn, with an increase of almost ₤17bn between 2009 and 2020. In 2019, Germany’s expenditure on cosmetic products stood at €14bn, closely followed by France (€11.44bn), the UK (€10.66bn), and Italy (€10.59bn). The American Society of Plastic Surgeons reported nearly $16.7bn spent on cosmetic procedures in 2020 alone, with expenditure on hair care products in the same year of $64.7m. (down, interestingly, from a high point of $89.95m. in 2017). But a preoccupation with beauty and fashion isn’t a Western preserve. In 2020, China became the second largest beauty and personal care product market (after the US) of 340bn CNY, up 13.8% on 2019 (with an overall 150% increase since 2010). Despite – or, perhaps because of – continuing concerns about travel and meeting in person in India, the cosmetic advertising industry projects an increase of 15.2% between 2019 and 2022, up 7.6% in 2021 alone. With climate change now an acknowledged global issue, the fashion industry admits it is the second largest consumer of water in the world and responsible for 8-10% of global carbon emissions. A ‘bonfire of the vanities’ of the fashion industry might not be scientifically advisable (!); however, a mirror on global fashion, when 2.4m. children died in January 2020 (most in the majority world), 690m. people suffer from acute hunger, and 2.5bn (30% of the world’s population) live in chronically dry areas (40% of the world), would suggest Savonarola’s violent questioning and repudiation of public values has lasting – indeed, increasing – plausibility.

Second, folly. The book Ecclesiastes is an obtuse, ancient text (c. 450-200 BCE) found in the ‘Writings’ (Heb. Ketuvim) of the Hebrew Bible and ‘Wisdom Literature’ of the Old Testament. Like wisdom literature generally, it does not squander its riches on the careless and lazy. However, what it says of human folly is frighteningly clear and apposite: human foolishness is presuming to be wise (1.15) or denying wisdom’s worth (7.1-8.1), expecting to live forever (1.16, 3.19) and ignoring evidence of mortality (2.10, 9.1-6), engaging in the selfish, stress-filled acquisition of wealth which someone else will enjoy (2.17f., 3. 9f., 6.1f.), being envious of the rich and powerful (4.8, 5. 8f.), idolizing pleasure (2.1-11), speaking in haste (5.2f., 7.8), turning a blind eye to evil and good (7.15f., 29, 8. 11f.), and forgetting to enjoy oneself (3.1f., 5.18f., 9.7-10, 11.9f.). That life, and life’s preoccupations, are potentially ‘meaningless’ and surrounded by all manner of ‘evil under the sun’, is pivotal for this ancient teacher of wisdom. Foolishness lies in valuing what has little, or passing, value: wisdom lies in looking beyond the immediate to the ultimate, in not expecting to understand everything, but recognizing a right ‘time’ for things (3.1f.) and the glimpses of ‘eternity [set by God] in the heart of man’ (3.11). There is a caustic honesty and directness here that George Eliot found attractive in Savonarola. We may not build a ‘bonfire of [our] follies’; we might, though, check the value and ‘reality’ of popular ‘vanities’ and how highly we rate them.

Lastly, the futility of war. As we have seen, George Eliot found the instability and vulnerability of the Florentine Republic (and the so-called ‘League of Venice’) – at war with itself and (in 1494) with the young, ‘affable’ French King Charles VIII (1470-1498) – redolent of the social turbulence and militancy of Britain (and many parts of Europe) in the mid-19th century. Like fashion, Eliot had little taste for war. An unfinished work is located during the Napoleonic Wars (1803-15), and her magnum opus Middlemarch (1871-2) has allusions to the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1), but Eliot’s despising of war is clear in her novel The Mill on the Floss 1860), where we find: ‘War, like other dramatic spectacles, might possibly cease for want of a “public”.’ In other words, war inspires and expresses other kinds of ‘vanity’, a love of ‘spectacle’, a quest for ‘glory’, a longing to be noticed. With Russia and the US and NATO allies brandishing more than swords on the Ukrainian border, the ‘vanity’ of war as an act of public politics and an invariably futile expression of ‘superiority’, The Bonfire of the Vanities is a good reminder that social – no, global – decay takes many corrosive forms. To add military expenditure to the debit owed to the suffering majority world would, I fear, be another form of fashionable folly.

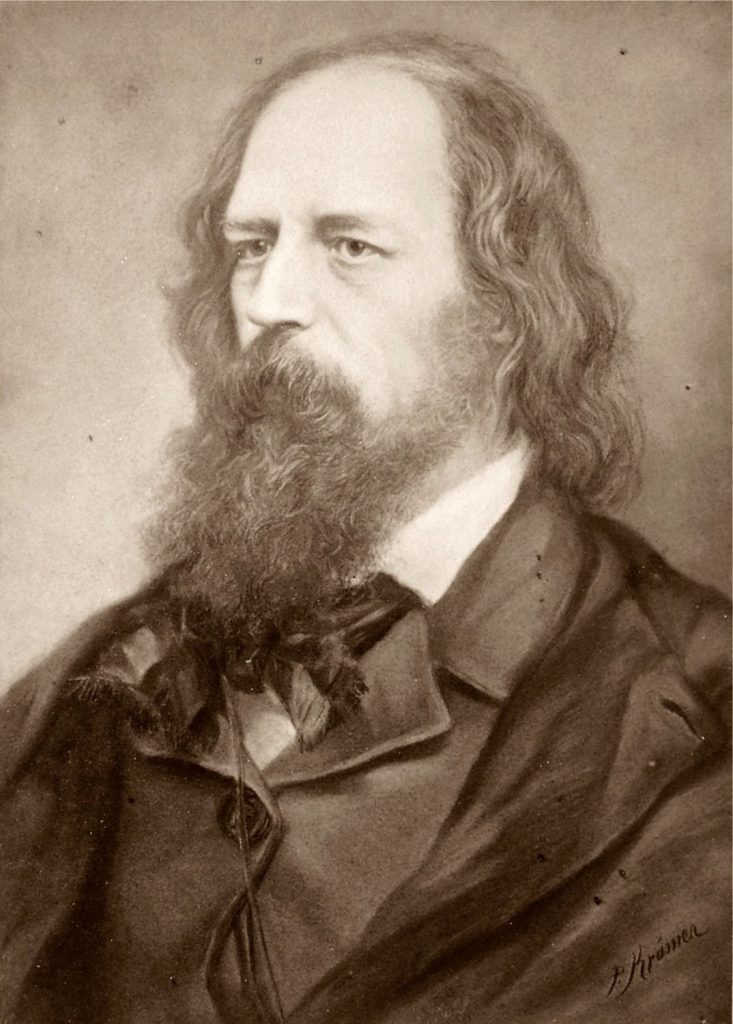

Let me allow the Victorian poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809-1892) the last word on the eve once again of Lent. His poem ‘In Memoriam A. H. H.’ (1850) has the following poignant lines, that provide, I suggest, a wise perspective on the fragility of life and the transience of modern, earthly ‘vanities’:

Be near me when the sensuous frame

Is rack’d with pangs that conquer trust;

And Time, a maniac scattering dust,

And Life, a Fury slinging flame.

Be near me when my faith is dry,

And men the flies of latter spring,

That lay their eggs, and sting and sing

And weave their petty cells and die.

Christopher Hancock, Director