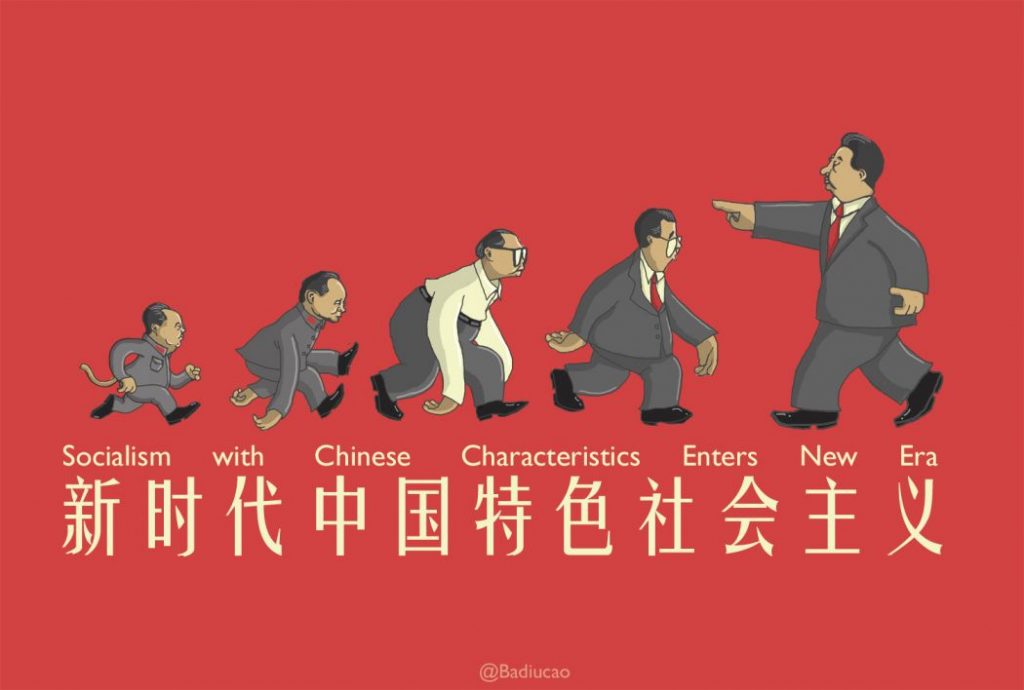

I am one of a number of optimistic China-watchers who believed in its potential to be a force for good in the world. Alas, its failure to fulfil this expectation has become a modern tragedy. In retrospect, China’s current trajectory should come as no surprise. Despite reporting to the contrary, its breakneck economic growth concealed a fragile substructure which has contributed to an inconsistent and ambivalent reputation on the world stage. Material prosperity has been at the expense of the radical disintegration of the traditional family unit and historic cultural values. It has created vast, internally contentious, inequalities across all key metrics, especially between affluent urbanites and impoverished rural labourers, and between the ruling cadre and the disaffected majority. The Chinese model of command-and-control capitalism, described without irony by the CCP (Communist Party of China) as ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’ (中式社会主义), has shaped the country’s macroeconomic agenda and done so without the inconvenience of waiting for a democratic mandate or securing of popular consensus. This has proved to be a blunt, at times cruel, instrument with unforeseen, and often undesirable, domestic consequences.

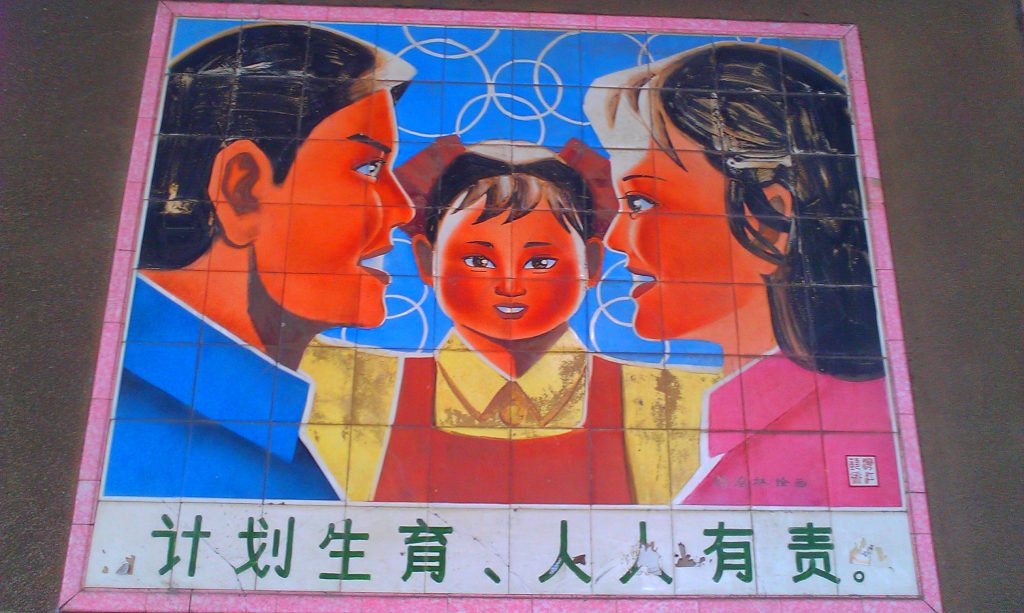

We need to understand how central – and vulnerable – President Xi Jinping (b. 1953), General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party from 2012, is in this context. Decrees ex cathedra from Xi[1] can override in a word existing precedent within China’s weak ‘rule of law’ and constitutional framework. In China (as in India), the President’s formal statements have messianic authority backed by a formidable military. This leaves Chinese society victim to the vicissitudes of personality and party. But it cuts both ways: when policies work (almost) everyone is happy, when they fail, or miss the mark, elites in China, including the President, are left exposed. Take the ‘one-child policy’ imposed between 1980 to 2016 as an example. As a strategy to reduce the population (and remind every Chinese home of their intimate obligation to the country at large), it succeeded in driving China to the demographic cliff edge of a divided, aging population. Experts believe China’s workforce is shrinking by as many as 3m. per annum, with one leading commentator on China’s political economy, Professor Shirley Ze Yu (Director of the China-Africa Initiative at the LSE in London and Firoz Lalji Institute for Africa), suggesting the median age of the population will be 51 by 2050 with a third over 65 by 2060. A dynamic young country? I think not. Who to blame? Chinese citizens know all too well: revolution is in their blood.

But deeper difficulties haunt President Xi and his party’s leaders. Chinese society is beset by a sense of internal and external ‘alienation’ akin to that of many Western societies in the post-WWII era. Recent (re-)lockdown of 45 Chinese cities – comprising almost two-fifths of the nation’s GDP – have cast doubt on the government’s handling of the pandemic as a whole and on the zero-COVID policy it lauded early on as vindication of its totalitarian governance. More than this, young professionals in late-2019 began to decry what they termed ‘996’ culture: the pervasive, corporate expectation of a 9am-9pm 6-day working week. When lockdowns swept across China in early 2020, their refrain became ‘lie flat’ (躺平), a chilling evocation of collective burnout. Over time, this has mutated again into cynicism and disrespect of China’s leadership with a slew of videos circulating (faster than algorithmic censors of China’s social media can take them down) of violent enforcement of COVID regulations by government representatives. Promises of the ‘China dream’ and ‘a peaceful Empire’ at home and abroad ring hollow inside and outside China. A precarious future has rendered many young Chinese pessimistic enough to give up on having children, despite restrictions on family planning being withdrawn in 2021[2]. Their mantra is now ‘let it all rot’ (摆烂). A happy, young, healthy China? No, New China is facing its greatest internal sense of disenfranchisement since its inception in 1949. This raises doubts in many minds about the CCP’s ability in its current form to maintain its widely touted vision of a ‘harmonious and moderately prosperous society’ (和谐小康社会).

But little of this has caught China’s elites unprepared or unawares. They have known for some time of their ticking demographic timebomb and vulnerable economic strategy. To counterbalance these – and to project a strong, convincing face to the rest of the world – they have led China to developing markets. In 2013, China passed the USA as the largest contributor of foreign direct investment into Africa, the old ‘Silk Route’ across Asia being transmuted into its flagship ‘Belt and Road’ (一带一路) infrastructure project.[3] Though COVID has impacted China’s population and public finances more than it admits to others, as the world’s second largest economy ($15.66 tr.) it still saw an 18.3% growth in GDP in the March quarter of 2021 (with 6% projected for the year). Meanwhile, its global reach extends (largely) uncontested. In Africa, where China has invested $2 tr. since 2005, its dominance in infrastructure development is clear.[4] As a Forbes article noted, the Asian superpower’s presence there is ‘ubiquitous’ (Forbes, 3 October 2019). In addition to its $1bn ‘Belt and Road Africa’ fund and $11bn Trans-Maghreb highway (from W. Sahara to Libya), in 2018 China provided a $60 bn aid package. In recent times, China has established itself (by fair means and foul) as Africa’s largest trade partner ($200 bn p.a.) with 10,000 Chinese firms now said to be operating across the continent.[5]

What of China and the world more generally? Though a permanent member of the UN Security Council since 1945 and part of the WTO since 2001, China has tended to abstain on controversial issues. In 2014, for example, it voted with Russia to veto a proposal to refer the crisis in Syria to the ICC. More recently, China has tried to play both sides over the war in Ukraine. They have stopped short of openly endorsing Putin’s invasion but criticized the West for imposing sanctions and supplying military aid. China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) said this of a June 15 telephone exchange between Beijing and Moscow:

Xi emphasized that China has always independently assessed the situation on the basis of the historical context and the merits of the issue, and actively promoted world peace and the stability of the global economic order… ‘All parties should push for a proper settlement of the Ukraine crisis in a responsible manner’, Xi said, adding that China for this purpose will continue to play its due role.

What that ‘due role’ should/will be is deliberately opaque. Historically, China’s official line has been that it does not interfere in the domestic affairs of other nations and expects foreign powers to follow suit. We hear echoes of this in the Russian leader’s commentary on the June 15 conversation with Xi:

Since the start of the year, the practical cooperation between Russia and China has been developing steadily… Russia supports the Global Security Initiative[6] proposed by the Chinese side and opposes any force to interfere with China’s internal affairs using so-called issues regarding Xinjiang, Hong Kong and Taiwan, among others, as an excuse.[7]

Since the end of the reformist presidency of Hu Jintao (b. 1942; Pres. 2003-2013), China’s playbook for soft power influence and economic cooperation has given way to a more aggressive, expansionist style. Xinjiang, Hong Kong and Taiwan are today’s toxic triad of issues it battles with internally and bristles over when challenged internationally.

So, what of the much-publicised mess in Xinjiang?

Xinjiang (Lit. ‘New Frontier’), or as it is technically ‘The Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region’ (新疆维吾尔自治区), was originally created under Qing dynastic rule in 1884. It extends to 1.6m sq.km (620k. sqm.) and is the largest province in China and 8th largest country subdivision in the world. Bordered by aspirant superpowers India and Russia, and a gateway to Pakistan and central Asia, Xinjiang’s significance for China’s ‘B&R’ initiative cannot be overstated. Beijing’s current sensitivity to the region is not surprising.

In the 2020 census 46% of Xinjiang’s 25.8m inhabitants self-identified as Uyghurs: most of the rest were Han Chinese. China officially recognizes 55 five ethnic ‘minorities’ under a Soviet-inspired classification system (ethnologists place the actual number nearer 300). The designation ‘Uyghur’, therefore, is misleading. Historically, it does not refer to one, contiguous ethno-linguistic group. The term is now used as an umbrella for 13 different tribal groups who have some shared history (overlapping with Turkic peoples in neighbouring states) and an Islamic faith. Under Xi’s 2012 policy of ‘sinicization’, minorities are now ‘Chinese peoples’ (中化民族), with their religio-cultural identities required to conform to centrally determined marks of ‘Chineseness’, including speaking (primarily, if not, exclusively) Mandarin and not their mother tongue.

Although absorbed peacefully into Mao Zedong’s (1893-1976) ‘New China’ in 1949, Xinjiang’s regional, ethno-religious identity remained unchanged and unchallenged, while deeper hopes for independence still ran strong. Tensions between the Uyghurs and majority Han (regional and national) government are not new, nor inexplicable. Several factors have converged of late to exacerbate the situation. We list seven here to shed light on China’s internal struggle to define itself and secure ‘buy-in’ from its vast and diverse population.

i. Muslim consciousness in Xinjiang (as elsewhere in China) is at the heart of the region’s culture and separatist politics. Crucially, Uyghur cultural sensitivities have been stirred, and aggravated, by inconsistencies in government policy. We focus here on one issue. During Deng Xiaoping’s (1904-1997; Chairman of the CCP’s Central Advisory Committee 1978-1989) liberalization of Chinese society and re-opening of a religious ‘public square’ in the 1980s, 1000s of mosques were built and blessed by government diktat in Xinjiang. Destruction of these sacred sites in the PRC’s purge of the Uyghurs of Xinjiang today is a direct, confusing, and, we must assume, embarrassing, reversal of this earlier policy.

ii. Xinjiang’s claim to self-determination reflects earlier policies and central government hopes for the region’s economic future. Three years prior to the official launch of the ‘B & R’ initiative in 2013, Xinjiang was designated the western gateway to China’s reinvigorated ‘Silk Road’ for culture, international trade, and access to China. Kashgar became a ‘Special Economic Zone’ (经济特区). Central and regional government invested heavily (economically and reputationally) in the province. Xinjiang was to wow the West. How times have changed! Economic interests, and Han entrepreneurs who had moved in to milk a new, expanding market, returned to booming Eastern seaboard cities.

iii. Globalization has rendered Uyghur Muslims aware of, and connected to, the theology and action of global Islam. Like China’s vast Christian community, Uyghurs are now self-consciously internationalized. On 5 April 1990, a year after the Tiananmen Square pro-democracy protests (April to June 1989), a religiously motivated uprising took place in Barin township near Kashgar, led by Zeydin Yusup (1964-1990), the charismatic head of the East Turkistan Islamic Party. The event shook the CCP to the core. At the time, Deng’s progressive liberality protected Xinjiang’s Muslims against reprisals. 9/11 and terrorist attacks worldwide have provided ammunition for those within the PRC wishing to impose a hard-line Marxist approach on religious faith and expression.

iv. The Uyghurs have suffered from the PRC government’s lack of religious self-awareness. At the outset of the recent crisis in Xinjiang, when the Religious Affairs Bureau failed to quell Uyghur protest, China’s leaders looked to the UK, EU, and US for advice on handling religious radicalization. This didn’t last long. An Islamist knife attack on police in Kashgar in 2008, and Muslim violence against Han-owned businesses and economic migrants in Urumqi in 2009 (in which 200 died), rumbled the central government and hardened its resolve to confront radicalization head-on rather than to seek greater understanding of religious identity and the causes of heightened political, religious and cultural tension.

v. China’s ancient quest for self-understanding lives on in 21st-century Xinjiang. The crisis in Xinjiang exploded when Beijing began to sense pressures it could not control, namely, mobilized urbanites, millions of globalized young, a booming church, socio-economic unrest. Prior to 2012, Xinjiang was celebrated as a national success. The PRC leadership believed ethnic identity would fade away as material prosperity grew, separatist passion and religious imagination converted by market forces. The calculation failed. Benefits overwhelmingly flowed toward Han economic migrants rather than residents, including Uyghurs. Inequality fired resentment. Religion became the rallying flag of a culture and identity in dissent. The post-Maoist vacuum was filled by such for many both then and now.

vi. The ‘ideological turn’ evident in China’s domestic and international agenda over the last decade reflects the PRC leadership’s suspicion of Saudi-sponsored Salafism. To Beijing, this expression of Islam is anti-modern and prone to violence. The consequence of this for Xinjiang is that Uyghurs are not only viewed through a one-dimensional, neo-liberal, socio-economic framework of asset-liability, but as deliberate, practitioner-partners of a politically destructive, metaphysical worldview.

vii. The crisis in Xinjiang has challenged global confidence in ‘The China Solution’ (中国方案 – announced 1 October 2016) and threatens the successful implementation of the ‘B&R’ initiative in (predominantly Islamic) Central Asia. Xi’s vision for China is that it offers an alternative (or, at least, complementary) approach to pressing global issues, such as climate change, economic volatility, globalization and terrorism. Xinjiang is a dreadful wake-up call internally and internationally that this may not be China’s forte.

As victims of misunderstanding, poor, unpredictable policies, greed, and expansionism, for the last ten years hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs have been interred in vast camps, or, as they are officially known, ‘Xinjiang Vocational Education and Training Centers’ (新疆职业技能教育培训中心 – VETCs). This has happened under the auspices of the government’s ‘de-extremification campaign’ (去极端化) and ‘counter-extremism’ agenda (反极端化). Initially, Beijing denied the camps existed, but in the face of mounting criticism and evidence their existence was finally acknowledged. In the so-called ‘Xinjiang Papers’, leaked official documents published by the New York Times in 2019, details emerged of a high-level decision to implement the ‘de-extremification campaign’ and develop the VETCs. In May 2022, further evidence from leaked Xinjiang Police files confirmed unequivocally grotesque human rights abuse inside the camps.

Under pressure to respond, in May 2022 a UN High Commissioner for Human Rights was (for the first time in seventeen years) permitted an official visit to Urumqi and Kashgar. In a statement afterwards, the UN High Commissioner, Michelle Bachelet, registered China’s progress alleviating poverty and its 5-year Human Rights Action Plan (2021),[8] but said this of the ‘de-extremification campaign’:

In the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, I have raised questions and concerns about the application of counterterrorism and de-radicalisation measures and their broad application – particularly their impact on the rights of Uyghurs and other predominantly Muslim minorities. While I am unable to assess the full scale of the Vocational Education and Training Centers (VETCs), I raised with the Government the lack of independent judicial oversight of the operation of the program, the reliance by law enforcement officials on 15 indicators to determine tendencies towards violent extremism, allegations of the use of force and ill treatment in institutions, and reports of unduly severe restrictions on legitimate religious practices. During my visit, the Government assured me that the VETC system has been dismantled… (emphasis mine).

Time will tell whether ‘dismantling of the VETC system’ is an indicator of China changing tack in Xinjiang under pressure from the international community. Serious questions remain about China’s ever-expanding surveillance system and its potential for abuse in the future. Growing unrest in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic is a ‘clear and present danger’ to the stability of the Xi regime. China – a country in turmoil? Absolutely. In Part II, I will look in greater detail at China’s future trajectory and how the international community might respond.

Paul Golf, Associate

[1] Although the General Secretary simultaneously holds the title of ‘president’, under China’s one-party system the highest political authority is invested in the most senior member of the Chinese Communist Party rather than a republican head of state. The role of ‘president’ is therefore only symbolic and ceremonial.

[2] Restrictions have been ostensibly removed for the Han majority, but Uyghurs and other minority groups are treated differently.

[3] The ‘economic belt’ is contrasted with the ‘maritime road’ crossing the Indian Ocean.

[4] China has gained a 40% share in Africa’s essential infrastructure development since 2011: Europe’s has reduced meanwhile from 44% to 34%, the US from 24% to 6.7%.

[5] A 2018 report by Le Monde, into widespread espionage by the Chinese state at the headquarters of the African Union (AU) in Addis Ababa, was denied by China and publicly received a tepid response from the AU. The fact that the server infrastructure was replaced and reconfigured without the involvement of Chinese tech firms suggests that the threat of Chinese espionage is taken seriously in Africa.

[6] The Global Security Initiative is China’s attempt to perform a ‘convening role’ in Asian and global affairs. It was proposed by Xi at the Annual Conference of the Boao Forum for Asia on 21 April 2022.

[7] Putin’s reference to ‘multipolarization’ in the MFA report is worth noting. The idea of a multi-polar world with several macro power-blocs, is central Putin’s thinking. This owes much to the political philosophy of the Muscovite theorist Alexandr Dugin (b. 1962). Dugin’s view of China is also illuminating. He urges caution. A weakening of China’s economy poses a long-term threat to Russia (esp. of knock-on effects on Kazhakstan and E. Siberia) even if short-term real politik suggests short-term economic and security benefits (cf. J. B. Dunlop, Aleksandr Dugin’s Foundations of Geopolitics,Demokratizatsiya 2004).

[8] The full text of the Human Rights Action Plan of China can be found on the official website of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.