Overshadowed internationally by the crisis in Ukraine, torn domestically between the Scylla of conflict over Taiwan and the Charybdis of ethnic regionalism in Xinjiang, and buffeted, as we saw in Part I, by waves of domestic discontent, Xi Jinping’s ‘New China’ faces the greatest challenges to its identity and coherence since its inception in 1949. If outsiders struggle to unravel the conundrum of China’s strongman image, China itself is a mass of internal contradictions and a stagnant warehouse of domestic issues. In Part I (‘China – a country in turmoil?’ 1st July 2022), we looked at the PRC’s headaches from COVID and a falling birth-rate, and, internationally, from its oppressive handling of the Uyghurs’ ‘minority rights’ in Xinjiang. My focus in Part II of this Briefing is China’s future and how the rest of the world could, and should, plan and respond.

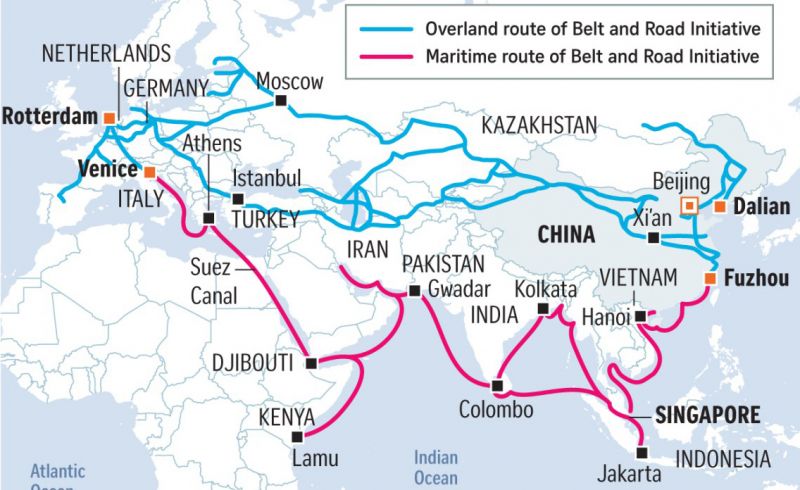

To-date, there has been remarkably little continuity and coherence in Western policies towards China; that is, until the last eighteen months. For much of Xi Jinping’s tenure in office (b. 1953; Pres. 2012-present), China has been on the front foot internationally. With Pax Americana a shadow of its former self, China stepped in with a seductive ‘soft power’ strategy to woo allegiance and shame rivals. Its pan-Asian ‘Belt & Road’ development initiative has bought regional political alliances and outbid historic Western involvement in the region. Likewise, China’s hard-headed, pre-emptive philanthropy and aggressive investment in Africa and Latin America. China has marched while the West has crawled, crippled by the 2008 financial crash, confused how to handle democratic uprisings in North Africa and wars in Syria, Iraq and Iran, and paralysed by the pandemic.

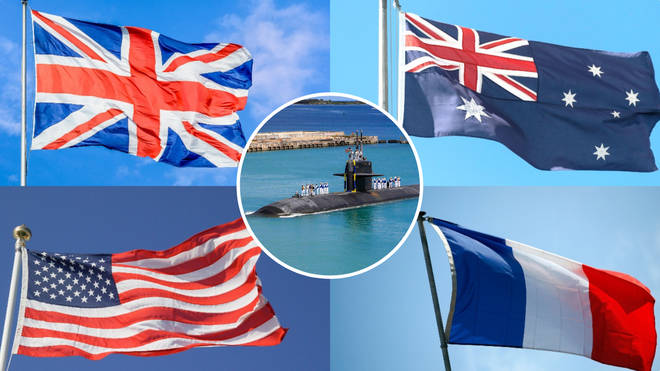

Leaving aside the crisis in Ukraine and COVID, the international community’s response to China’s social, economic, political, and military expansionism has been at best tardy, at worst irresponsible. It took until July 2021 for G7 to propose what has now become ‘The Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment’, a $600bn development plan to rival PRC’s $2.5tr. global investment in emerging markets over an 8-year period. It wasn’t until September 2021 that the AUKUS security pact was signed. To many, this signalled the first significant Western response to the dramatic increase in China’s naval capability. In July 2022, the US and UK’s domestic intelligence agencies issued a substantial joint statement on the threat of PRC technological espionage.

So, why has the West taken so long to respond? None of China’s geopolitical, economic, and military actions are unexpected or new. Political and economic volatility in Europe and America in the early-21st century may be one reason, but another is their shared uncertainty about China’s true intentions and stultifying inability to agree what those are. To beneficiaries of China’s benevolence, antagonism is stupid. To geopolitical rivals, China’s threat is real. That said, few doubt that under Xi Jinping, China’s approach to its international relations has become tougher than under his (retrospectively) collegial predecessor, Hu Jintao (b. 1942).

Since its humiliation in the first and second Opium Wars (1839-1842), and bitter 20th century conflict with Japan (1937-1945), China has worked very hard to project an image of unity and invincibility. But its widely acknowledged 200-year identity crisis has taken its toll internally and internationally. From its earliest encounter with Western industrialized nations at the end of the Qing Dynasty (1636-1912), through its 20th century Republican phase (1911), internal ‘warlord’ era and civil war (1927-1949), and conflict with Japan (1937-1945), China has struggled to interpret itself to itself (in light of its ancient culture) and to others (as part of the postmodern global community). It has often been easier for China to say what it is against or is not than what it is or stands for. Of course, this is not inexplicable given its emergent communist identity and our rapidly changing world. But there are paradoxes in China’s thought and behaviour. Consider: China is very keen to define itself as ‘not the West’ (and, at times, ‘against the West’) while reverting – more, perhaps, than at any point since the founding of the CCP (1949) – into explicit ideological dependency on the thought and schemata of German philosopher Karl Marx (1818-1883), albeit nowadays with the cultural embellishments it likes to call ‘Chinese characteristics’ (中国特色). And then there is the paradox of China’s frequent flaunting of its unbroken history and possession of the world’s oldest writing system, while all the while downgrading its history in defining its ‘destiny’ as ‘New China’.

Hard as it may be for Western minds to grasp, Chinese culture does not shy away from paradox. Western imagination, framed by the legacy of Christendom and the laws of empirical veracity, struggles with this. China’s paradoxes are multiplied in, and by, the West. So, the major political and economic competitor (especially in emerging markets) becomes the necessary strategic partner; the military threat and security risk becomes central to global supply chains and tackling climate change and biodiversity loss; the bastion of Western affluence and financial stability is also the threat to the best kinds of Western values and global stability. Every foreign policy playbook has to reckon with these paradoxes in its engagement with an equally paradoxical PRC.

But how to respond? Surely, all sides must resist the urge to retreat into siloed power blocs of idiosyncratic nationalism and instead work to confront the greater humanitarian and ecological threats we all face together. In the ever more integrated global system of ecology-economy, the threat of the ‘other’ comes from the ‘unknown’. That is why it is not only important for the West to build a proactive and integrated strategic response to China, but also strain to unravel China’s internal logic. It is too simplistic to define the actions and intentions of China in black and white terms. We must understand the rationale behind those actions, even (or especially) those that run contrary to Western values, to offer a legitimate and practical alternative.

Bearing all this in mind, as in Part I, I want to propose now seven referents for Western engagement with ‘New China’ as it moves towards its centenary in 2049.

(i) International pressure impacts China’s view of Human Rights. China, both officially andconceptually, sees the ‘rule of law’ as subordinate to government policy, and (once again) in the Xi era to the leader’s personal agenda; but analysis of PRC media shows a subtle shift in position. The third 5-year ‘Human Rights Action Plan of China’ (HRAP), published in September 2021, contains commitments to everything from healthcare to freedom of religion, from environmental actions to raising living standards which reach much further than China’s initial Human Rights policy (2009). China may accuse the West (especially the USA) of ‘hypocrisy’, but its language and repositioning on human rights is clear new evidence that Xi’s hard-line approach is not immune to criticism nor unconcerned to save face if policy statements are palpably ineffective or contradictory. But notice this: from the outset, HRAP makes clear it is to be interpreted and implemented in accord with ‘Xi Jinping Thought’. This gives President Xi carte blanche to reframe the policy whenever he chooses, but it also binds his name and standing into the policy’s success and failure. Like Xi, China as a whole is demonstrating political and geopolitical awareness that it does not and cannot expect to act in a relational vacuum. Actions have consequences, as its tenuous ally Russia has discovered to its cost in Ukraine – and China doesn’t want to risk collateral reputational damage.

(AP Photo/Ng Han Guan)

(ii) Religious freedom remains a contentious issue in China. Section II:4 of HRAP is on ‘Freedom of Religious Belief’. Four religions are named. Concessions differ. Buddhism and Taoism fare best, with overt guarantees of their legal right to practice, develop, and integrate into contemporary Chinese culture. Islam comes next with explicit support for the state-run China Islamic Association (CIA, 中国伊斯兰教协会组织) and assurances that Muslims may make state-registered pilgrimages to Mecca through the national Islamic Association. This is an important concession. It aims to appease Muslims (and others) angered by the government’s action in Xinjiang while monitoring access to Saudi Arabia through the CIA and its surveillance teams. The section on Christianity comes last and is revealing, focusing purely on the ‘transformation of Christian thought’.[1] Understanding this requires reference to Xi’s 2012 policy of ‘sinification’; that is, for ethnic minorities and religious groups – including Christians – to ‘sinify’ their literature, beliefs, and ritual so they conform to Xi’s view of ‘Chinese-ness’ and ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’.

From the perspective of the international community, the growth of the Christian church in China has had a knock-on effect on PRC policy towards religion in general. Though there are perhaps 23m. ethnic minority Muslims in China, statistics at the start of Xi’s presidency put the number of Christians – who were mostly Han converts – at anywhere from 80-150m, up from ca. 100,000 in 1949.[2] China was losing control of its core cultural and ethnic identity. The repression of Uyghurs in Xinjiang is a cruel demonstration that Xi does not want to lose China, or his definition of ‘Chinese-ness’ on his watch.[3] Prompted by the rapid growth of the Christian church, every religion is now to be brought into line. Religious identity per se has been toxified. In the case of Xinjiang, it is both ironic and tragic that a government that claims such powers demonstrates such paranoia. The breadth of HRAP 2021 reflects the PRC’s concern to appeal to and to match the holistic claims and social provision of China’s religious communities. These are not matters of secondary concern for China. As in India, literacy in the multiple ways in which religion manifests and emerges in Chinese society is crucial for any successful foreign engagement.

(iii) HRAP 2021 reflects a new approach to China’s demographic crisis. Part I addressed the broad impact of China’s ‘one-child policy’. Population growth has stalled. Family life has been traumatised. Youth disenfranchisement from ‘New China’ is palpable. The plug on the policy has been pulled. HRAP 2021 references two policies that reveal a sense of urgency in addressing thorny demographic issues. First, measures ‘alleviating women’s burden of childbearing’ (section IV:2). This includes a commitment to increase public and private childcare and the trialling of new types of parental leave. The hope to motivate women to have more children is clear. Second, in the absence of a developed geriatric care infrastructure, a nationwide system of enhanced care for the elderly is promoted (IV:4). A strong GDP is required to cover the significant costs of such policies. But there is another side to China’s waning population and weakening work force. Much of the income in China’s burgeoning middle class is held in real estate. Vast urban developments of residential properties, schools, and other amenities are at risk from declining demand. This impacts local government, which relies heavily on the sale of property leaseholds to raise operational capital. A smaller and older population exposes China to a subprime catastrophe – witness the property fallout from the Evergrande crisis.[4] Current policies do not easily allow for a major influx of immigrant workers to fill the gap, so international expansion becomes one of few options for China. In coming decades, these problems will be felt more acutely. Without credible economic and demographic alternatives, the risk increases of more radical expansionism.

(iv) China is betting heavily on emerging markets. This takes many forms. Reciprocal trade agreements and indenturing debtors in international development partnerships are the tip of the iceberg. In April 2021, Montenegro was denied a $1bn bailout by the EU to cover a loan repayment to the ‘China Road and Bridge Corporation’ (for building a highway). This left a European nation exposed to ceding assets to the China Exim Bank (中国进出口银行), one of three ‘policy banks’ (政策性银行) that operates under the State Council in relation to foreign investments and emerging markets. At the end of 2021, Pakistan – a strategic regional ally of China – narrowly avoided defaulting on a $14bn loan for ‘Belt &Road’ projects in the country. In June 2022, China increased the loan by $2.5bn, thus tightening its financial and political grip on Pakistan. To China, such acts enhance its global influence and safeguard its own future. The US and EU ‘Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment’ is an important step towards a global financial safeguard against China’s risky bet on volatile emerging markets. Cooperation with China must remain on the table – but circumspectly – to avoid zero-sum competition on the one hand, and hostile takeover on the other.

(v) China is moving towards an information-based and services economy. Hitherto, China has grown through a dynamic manufacturing economy. A shift towards information technologies and service industries is not straightforward, however. A culture of risk and innovation is part and parcel of a successful entrepreneurial economy in the modern world. This does not map easily onto China’s increasingly dictatorial and repressive style of government. Creativity and innovation thrive on the dream of something better and permission to question the status quo. China’s public and professional institutions, meanwhile, rely on a culture of conformity and deference to authority. In the recent past, China looked to the West for models of success; no more. Time will tell whether its intended move towards an information- and service-based economy can succeed without allowing room for creative dissent. In the meantime, the ‘brain drain’ of China’s intellectual, artistic, and entrepreneurial elite runs strong, with talented, ambitious young Chinese making new lives in liberal democracies. The West ought to take note of the potential of fostering dialogue and relationships with these key individuals, and not lose sight of its own role in technological innovation.

(Elaine Thompson-Pool/Getty Images)

(vi) The Chinese government is fearful. Totalitarian regimes are built on fear. This is true of Xi’s China. Purges of detractors and dissenters are commonplace. They also expose fissures at the heart of the ruling party. President Xi’s adjustment of the constitution, so he (like Putin) can serve in perpetuity, was only possible because he threatened or removed critics and rivals under his ‘Anti-corruption campaign of the 18th National Congress’ (中共十八大以来的反腐败工作). The simple fact is a weak ‘rule of law’ and culture of strongman leadership has meant few have accrued power, wealth or influence in ‘New China’ without direct and indirect involvement in some kind of corruption. Lack of a mature legal structure has meant economic success at home and abroad involved for the vast majority ‘going the back door’ (走后门). No one is entirely innocent. Even some who have sought to use their new wealth to break free from CCP controls overseas have been chased, chastised, imprisoned, or conveniently ‘disappeared’. Even the once free-market entrepreneur Jack Ma (b. 1964), former CEO of Alibaba, has become a Party stooge. Elites within the Party become victims of the system. We shouldn’t underestimate how many in China toe the party line in public while dreaming of a different future for their country.

(vii) China is vulnerable to Western claims to the moral high ground. The text and subtext of much publicity out of Beijing is ‘the China Way’ is better. Some believe this, many do not. The plight of the Uyghurs has undermined claims of a ‘benevolent China’. Quitting his predecessor’s ‘soft power’ strategy, Xi Jinping is gambling on China being able to buy itself a better global reputation. Many in the CCP question this. Hence, the continuing presence of officials’ children in elite western schools and their palpable desire for a better future for their children than in ‘One Party’ China.

The anti-American media critic Sima Nan (司马楠; b. 1956) is an interesting case in point. Hailed as a patriot for his assaults on US Human Rights, Nan caused a scandal when it emerged back in 2012 that his family lived in the US. His reply when challenged? ‘I attack the USA for my job; I visit the USA for my life.’ Such cases are not uncommon. Western powers should factor in the life and times of the expatriate offspring of China’s elites: in time they may hold the key to ‘New China’s’ new future.

Paul Golf, Associate

[1] The published English differs significantly here from the Chinese original: Original: 加大对天主教、基督教神学思想建设及成果转化的支持和保护. Official English translation: ‘[HRAP] supports and protects Christian denominations in their efforts to adapt Christian theology to the Chinese context and communicate it to the believers.’ Actual meaning: ‘[HRAP] increases its support and protection of the construction and successful transformation of Roman Catholic and Christian (sic) theological thought.’

[2] NB., the number of Muslims and Christians is probably higher, but PRC statistics are famously politicised. Religion is not supposed to flourish in an ideal Marxist state.

[3] The meticulous analysis and dissemination of evidence by German anthropologist Dr. Adrian Zenz (b. 1974) are almost certainly behind the PRC leadership’s engagement with interlocutors on the Xinjiang issue.

[4] On the crisis, see the recent Bloomberg article: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-01-27/china-is-said-to-weigh-breaking-up-evergrande-to-contain-crisis.