Setting the scene

Life and faith are mysteries. We enter and experience both through factors beyond our understanding and control. Our parentage and DNA, our appearance and abilities, our predispositions and cultural formation are among life’s ‘givens’, it seems as if by chance. We sometimes – no, often – wish it were not so. Hence, the screening of fetuses, the lust to travel, the counter-cultural will to ‘convert’, the wish to be someone and somewhere else. It is a cause of note and wonder, then, when options to change, to avoid harm or to relocate are resisted, when difficult ‘givens’ are accepted, celebrated even. Such is, in my experience, the lot and dominant mindset of many members of the minority Christian community in the often-hostile Islamic Republic of Pakistan in the early 21st century. Not that the plight or profile of Pakistani Christians is unique, if studies of religious freedom and the psychology of ‘believers’ worldwide are to be believed, but it is still a poignant, frequently painful, and yet willingly embraced, predicament. But why is that? And what can be learned from this? This Briefing is a study of the specific situation of Christianity in Pakistan and the broader phenomenon of the will to own and accept an identity when under pressure to renounce it.

Two contextual points.

First, if life is randomly assigned and beset by chance, death is all too certain, however varied, and unplanned the experience of dying. Mortality has preoccupied the thoughtful for millennia. Death rituals and community customs to honour the departed are inscribed in the annals of global human history. Understanding them sheds light on cultural habits that interpret ‘givens’ in life. Statues honouring the fallen in war speak as much of the way a society sees life as interprets death. The ‘unknown warrior’ is a trope for the forgotten in society, the grave a place of pilgrimage defining the priorities of the living. The self-sacrifice of the soldier, like the embattled believer, makes clear in very tangible terms that they own, to the ultimate degree, an identity randomly assigned.[1]

I begin here because to walk around a Christian graveyard in Pakistan is to be reminded of those who lived and died aware of having a cultural and spiritual identity outside the norm: that they, like soldiers in war and religious martyrs, had lived and died for a greater, higher, cause. To understand the mindset of religious minorities – including Christians in Pakistan – we must reckon with the psychological and social power of an identity randomly assigned and of a cause and identity consciously chosen. Indigenous, minority Christian communities around the world – perhaps more than their counterparts in majority Christian countries – are conscious of being ‘citizens of heaven’ (Philippians 3.20-21) and of a country on earth. And for both of these ‘countries’, history confirms, they are very often equally ready to die.

Second, if questions of identity and death map on to the mindset of religious minorities worldwide, so, too, does the historic, socio-political, phenomenon – and contemporary resurgence – of nationalism. Though tribalism remains a potent cultural, social, and political force globally, from the birth of the notion of a ‘nation state’, in (probably) the 15th century, its frequently fractious offspring ‘nationalism’ has laid on citizens the additional burdens of patriotism, conformity, and (sometimes) National Service in the military. With a power to create, and enforce, a distinct and divisive national identity, nationalism, though conceived as an instrument of harmony and peace, has acted as a stimulus to conflict and division. What’s more, religious nationalism has its own unique way of persuading, cajoling, and justifying its actions. Religious minorities are in the crosshairs of nationalist animus. ‘Diversity’ globally esteemed is locally despised, with minorities having few, if any, rights. However, and we will return to this later, to the generous spirited, far from weakening a society, religious and ethnic diversity, is a cause and symbol of national strength. Critics of minorities are, after all, frequently the cause of international tension and internal division. Imposed unity is weak. Willing inclusion, as a feature of national identity, a cause of pride.

Christians in Pakistan

So, what of the context in which we should understand the Christian minority in Pakistan? Three realities warrant attention.

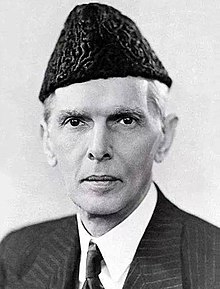

First, at the time of Partition in 1947, Pakistan was, like India, conceived to be an inclusive, multi-religious, secular state. As the founding father of modern Pakistan, the Quaid-e-Azam (Lit. ‘Great Leader’) Muhammad Ali Jinnah (1876-1947)[2] said, it was to be a ‘separate state for the minorities of India’,[3] including India’s (minority) Muslim citizens and Christians. Here is Jinnah addressing the nation’s first Constituent Assembly, on 11 August 1947: ‘You are free! You are free to go to your temples. You are free to go to your mosques or to any other places of worship in this State of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion, caste, or creed – that has nothing to do with the business of the state.’[4] The new Republic of Pakistan was, to Jinnah, to be a place where all could and should live under the rule of law, without restrictions on their religious faith, identity, beliefs, and practices. As in India, Christians in the new secular Islamic Republic of Pakistan welcomed this vision. Jinnah praised Christian leaders frequently in his early speeches for their endorsement of the country’s new Muslim leadership and their inclusive religious vision.[5]

As a majority Muslim country today, many in Pakistan are either ignorant of, or reject, the founding vision Jinnah articulated, and the repetition of principles outlining Pakistan’s inclusive state ideology in the Objective Resolution and Constitutions of 1956 and 1962, and Article 25 of the 1973 Constitution.[6] The fact Muslims were once a minority in India has done little to inspire protection of minority rights in Pakistan today. Jinnah held that Islam is not defensive or conservative, that identity and ideology are separate concepts,[7] and thus equality and freedom are de jure concomitants of a modern, secular, religiously plural, multi-ethnic, nation. However, to his contemporary detractors, Jinnah sold his Muslim heritage for secular Western acclaim. The fact that the Qur’an and Sunnah both envision religious tolerance is quietly sidelined. As Qur’an states, ‘For you is your religion, and for me is my religion.’ (109.6), and again, ‘There is no compulsion in religion’ (256.6).

Second, post-partition Pakistan has drifted more or less inexorably towards a repressive Islamist identity. With 90% of Pakistani’s 235+m citizens self-defining today as Muslims, the (est.) 2.5m. Christians form a small minority presence.[8] Far from enjoying the fruit of a generously inclusive Constitution, as originally conceived, Christians have consistently faced discrimination at work and in the community, lived in substandard accommodation, and, most recently, faced brutal attacks and flagrant intimidation. Ideology and insecurity foster intolerance.[9] However, as intimated earlier, the multi-generational identity of many Pakistani Christians tends to imbue them with a sense of an inalienable obligation to their ‘heavenly’ and their earthly citizenship. But this ‘dual citizenship’ has been sorely tried and tested of late. Widely reported incidents of mob violence, church burning, physical attacks, executions, imprisonments, and public trials for blasphemy – with minimal intervention and protection by the authorities[10] – have sent shockwaves of fear through Christian ranks. Poor, low caste, Hindu converts to Christianity (especially, Punjabi and Dalit families who trace their roots to the colonial era) have suffered most discrimination and have the least capacity to resist.[11] False accusations of ‘conversion’, ‘blasphemy’ and ‘inciting violence’ have fueled Christian fears … and anger.[12] As Sara Singha notes, the minority Christian community in Pakistan is now in an advanced state of distress, with uncontrolled violence inspired by unconfirmed accusations of blasphemy.[13]

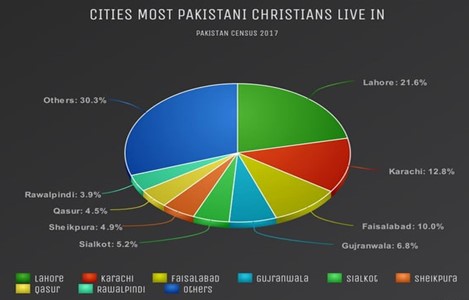

Third, like many ethnic minorities around the world Pakistan’s Christians have tended to gather in identifiable neighbourhoods, towns, and cities. This has enabled them to support each other, worship together and, when needed, protect one another. It has also meant that those who will these Christians harm have an identifiable physical focus for their animus. Historic churches, once landmarks of Christian faith and tradition, have become symbols of anti-nationalist disloyalty and subject to criticism and attack. The predominantly urban profile of Pakistan’s Christians has also meant, for good and bad, that their life and identity have been associated with international values and individuals. Subversion is suspected.

Prejudicial treatment of minorities in Pakistan, including the Christian community, has led the US Commission on International Religious Freedom to identify Pakistan as a country of ‘particular interest’. Other commentary would go further and identify 21st century Pakistan as one of the least religiously tolerant and inclusive countries in the world.

Four specific issues

If we drill down into the situation on the ground for the Christian community in Pakistan, four issues stand out.

First, Pakistan’s application of its increasingly strict blasphemy laws. Charges of blasphemy have been, and remain, widespread in Pakistan, as in other conservative Muslim states. In the recent past, blasphemy laws have been used as instruments of social control as much as a defense against desecration of the Qur’an and other Muslim texts, traditions, and figures. Changes to the blasphemy laws between 1980 and 1984 (i.e. while General Zia ul-Haq was in power)[14] have led to a sharp increase in court cases and convictions. Between 1987 and 2016, 1472 people were charged with blasphemy offenses. Of these, 730 were Muslims, 501 Ahmadiyya, 205 Christian, and 26 Hindus, according to the Lahore-based Centre for Social Justice (CSJ). Statistically, Christians who compose barely 1% of the population have faced 13.9% of the country’s blasphemy trials.[15] In 2021, seven Christians were charged with and imprisoned for blasphemy. In 2022 another two suffered a similar fate.

Second, as indicated earlier, anti-Christian discrimination has a long history in Pakistan. Low caste Hindu Christian converts find themselves employed in unattractive sanitation work – always a perilous occupation – and thereby further marginalized within society. Prospects of socio-economic advancement among Christians are limited. According to the CLJ, a ‘cycle of abuse’ and discrimination exists in Pakistan’s present approach to ethnic and religious minorities. Thousands of instances of abuse have been recorded by the CLJ.[16] There is little sign of this situation improving. The violence against Christians and Christian settlements in the Jaranwala area of Faisalabad,[17] Punjab, on 16 August 2023, by a crowd orchestrated by the politically and religiously radical Tehreek-e-Labbaik group, remains as a standing indictment of the willful disregard of the plight of Christians by Pakistan’s police, military, and political elites. The (caretaker) Prime Minister Anwar ul Haq Kakkar (b.1971; PM from August 2023) condemned the attacks and promised harsh reprisals,[18] but the perpetrators of the atrocity remain at large. According to Human Rights Watch, the Faisalabad police department is aware that the charge of blasphemy that incited the rioters was very weak.

Third, the incident and its aftermath in Faisalabad shed important light on the mindset and motivation of Pakistan’s religious minorities and political leaders. Four strands in this can be discerned:

1. mutual concern and concerted action by minorities in Pakistan. After the violence in Jaranwala, leaders from Christian, Sikh and Hindu communities collaborated calling for the perpetrators of the violence to be held to account.[19] Punjab’s caretaker Chief Minister Mohsin Raza Naqvi, a media mogul, met with religious representatives, voiced sympathy for those who had suffered, called on the country to unite against such actions and attitudes, and encouraged minorities to develop an agreed strategy to prevent a repeat of the incident.

2. Christian leaders and government officials invoked the law to provide clarity, security, and a system to curb violence against minorities. Though Christians called 18 August 2023 ‘a day of condemnation’, and lawyers staged a demonstration in the High Court in Lahore,[20] the Roman Catholic Archbishop Sebastian Shaw (b. 1957) and United Protestant Church of Pakistan Bishop Emanuel Khokar (from 2010) called for a swift legal response. The Governor of Punjab, Baligh Ur Rahman (b. 1966; Governor from May 2022), similarly denounced the violence and warned against individuals and communities taking the law into their own hands. The Vice President of the Lahore High Court Bar Association, Rabbiya Bajwa, also appealed to the law as a defense against wanton violence and intra-communal abuse.

3. The law was cited to protect minorities against violence and false accusations of blasphemy. Both Ms. Bajwa and Governor Rahman reminded Punjabis at the time of the legal basis for religious harmony and mutual respect. The latter stating, ‘Islam teaches us peace, tolerance and brotherhood.’ Adding, as Jinnah had, ‘The Constitution neither allows hurting religious sentiments, nor … hurting anyone’s life and property. The minorities have equal rights in the Constitution and law of Pakistan.’[21] Writing in the Pakistan Times,Ms. Bajwa rejected mob violence and called for sensitivity to all communities in Pakistan.

4. Politicians and activists from different religious traditions united in condemning the violence. Hence, we find expressions of sympathy and regret articulated by the former Prime Minister Yousuf Raza Gilani (b. 1952; PM 2008-12) and by the Human Rights and religious freedom activist Pervez Rafique. The latter called for collective action against those who sought to fracture social harmony and Christian-Muslim relations, whilst also providing guarantees of safety to churches and individual Christians.

Ten propositions

The tragic events in Jaranwala have led to public reiteration of Pakistan’s constitutional inclusivity. In light of this, I suggest the following be action points going forward:

• The government of Pakistan endorse the 11 April 2023 resolution at the National Assembly that reaffirmed its commitment to the 1973 Constitution and thence to safeguard the socio-economic and religious rights of non-Muslims.

• Policies be developed to ensure there be no repeat anywhere in Pakistan of the violence in Jaranwala and appropriate expressions of solidarity with sufferers be voiced.

• Action be taken to protect the Christian minority in Jaranwala and justice in the courts be demonstrated by the prosecution of the insurgents.

• The government of Pakistan recommit again publicly to protect the rights and freedoms of religious minorities, including the right to meet, live and worship in safety.

• The regulatory bodies in Pakistan reaffirm the right to freedom of expression as enshrined in international Human Rights law.

• To avoid bigotry and aggravating ill-will, judicial reforms must include training for the judiciary (for local officers in particular) on the character, faith/s and culture/s of minority communities.

• Independent enquiries must be established in law as the appropriate response to ethnic and religious violence, especially on the scale seen in Jaranwala, and the legal system and its officers be held to account if the perpetrators of violence are not prosecuted.

• Action be taken against those who kidnap, or – as in the case of corrupt police officers – turn a blind eye to the kidnapping of, members of religious minorities.

• Parliament approve anti-hate speech legislation to outlaw instruction in mosques and madrasas that foments animosity towards non-Muslim minorities in Pakistan.

• School, college and university curricula be monitored to include education in world religions and exclude the defamation, misrepresentation, and marginalization of minority groups in Pakistan.

Conclusion

We began considering the profile and mindset of religious minorities, and especially of the Christian community in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. We end registering the impunity with which Pakistan’s inclusive secular Constitution is ignored and perpetrators of violence succeed. Freedom to offend breeds lawlessness. Systemic injustice undermines the rule of law. Extremism demotivates and destabilizes the lives of the majority. Pakistan’s culture and community spirit are threatened in the early 21st-century by coercive nationalism and oppressive radicalism. The inclusive, secular, libertarian ideals of the nation’s founders are under threat as never before. The once independent media has little room now to speak up freely for the well-being of all. The impact of this noxious atmosphere on minorities is clear. They must choose to be faithful to the historic traditions of their nation and ‘tribe’ or bow to new voices who have captured the microphone and call for their blood. As indicated at the outset, the remarkable fact is that, though their dignity and identity be abused, most Christians in Pakistan still love their country and culture and long for its flourishing.

Dr Iram Naseer Ahmad – Research Associate

[1] On this theme, see the fascinating discussion of identity, ritual, and nationalism inspired by Benedict Anderson’s (2006), Imagined Communities (NY: Verso).

[2] Jinnah was a lawyer-politician who led the All-India Muslim League from 1913 and became the first Governor-General of Pakistan on its formation on 14 August 1947.

[3] Cf. K.M. Saqib, H. Mukhtar, and M.S. Asghar (2023), ‘Analytical study of Article 25 of the Constitution of Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973’, Journal of Positive School Psychology 7.2. 2: 81-8.

[4] On this in general, see M.R. Afzal (2009), Pakistan: History and Politics 1947-1971 (Oxford: OUP); S.P. Cohen (2004), The Idea of Pakistan (Washington, DC: Brookings Institute).

[5] Cf. S.M. Assim (2022), ‘Christian Missionaries Enterprise during Pakistan’s Pre-Partition Era; A Case Study of Punjab’, Central Asian Journal of Social Sciences and History 3. 12: 269–84.

[6] Cf. I. Khalid and M. Anwar (2018), ‘Minorities under Constitution (s) of Pakistan’, Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan 55. 2: 51-62.

[7] Cf. A. Majid, A. Hamid, and Z. Habib (2014), ‘Genesis of the Two Nations Theory and the Quaid-e-Azam’, Pakistan Vision 15. 1: 180-192.

[8] Cf. in the 2017 Census they represented 1.27% of the population. However, statistics on minorities in Pakistan are hard to secure and confirm. In 2018, there were a reported 3.63m non-Muslim voters in Pakistan, of which 2.64m were Christians (+ ca. 1.77m Hindus, 167k Ahmadi, 31k Baha’is, 9k Sikhs, 4k Parsis and 2k Buddhists and others).

[9] Cf. E.H. Basri (2016), ‘Constitutional Provisions for the Rights of Non-Muslim Minorities in Pakistan’, Al-Idah 33.2: 129-42.

[10] Cf. M. Mehfooz (2021), ‘Religious Freedom in Pakistan: A Case Study of Religious Minorities’, Religions 12.1: 51: https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010051.

[11] On this, see D.A. Latif, S. Zaka and D.S. Ali (2023), ‘Religious freedom and minorities’ discrimination: a case study of Christians’ socio-economic discrimination in Pakistan’, Bulletin of Business and Economics 12.1: 73-80: https://doi.org/10.61506/01.00012

[12] Cf. M. Nazir-Ali (2023), ‘What Is behind the Mobs in Pakistan?’, The Round Table, 1-2.

[13] Cf. S. Singha (2022), ‘Caste Out: Christian Dalits in Pakistan’, The Political Quarterly 93.3: 488-97.

[14] Cf. V. Girotra (2009), ‘Civil and Military Elite Relations in Pakistan during Zia Ul Haq Era’: https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in:8443/jspui/handle/10603/201236.

[15] Cf. A.K. Mahmood and I.A Chishti (2019), ‘Blasphemy Law and Its Interpretation a Pakistan’s Perspective’, Al Tafseer 34.

[16] Cf. N. Walter and M.M. Khan (2023), ‘Analyzing Post 9/11 Religious Freedom in Pakistan: A Case Study of Christian Minorities’, Global International Relations Review, VI: 39-48.

[17] Cf. According to Human Rights Focus Pakistan (HRFP) 19 churches were set on fire and 89 homes destroyed.

[18] Cf. A. Ahmad, et al (2023), ‘Protection and Respect of Non-Muslims in Pakistan, An Analytical Study in the Context of Jaranwala Incident’, OEconomia 6.2: 423-33.

[19] A key meeting was attended by the Anglican Bishop Nadeem Kamran, the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Lahore, Bishop Sebastian Shah, Dr Allama Muhammad Hussain Akbar, Dr Raghib Hussain Naeemi, Amarnath Randhawa, Rohia Maufadi, Pastor Mehnual Khokhar, Sardar Kalyan Singh Kalyan, Pandit Bhagat Lal, and Maulana Zubair Hasan.

[20] NB. women lawyers, carrying placards, were prominent in this protest.

[21] Cf. National Commission for Human Rights, Jaranwala-Incident Report (Lahore: 2023): https://www.nchr.gov.pk/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Jaranwala-Report.pdf.