‘Animal rights’ activists at COP26 protested with environmentalists at inter-governmental inaction. PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals), Viva! and OneKind hit the streets with banners that declared ‘Meat=Heat’, and ‘Fight Climate Change with Diet Change. Go Vegan.’ Glasgow’s blue buses agreed: ‘You can’t be a meat-eating environmentalist’. To support their cause, activists cited Oxford University research that concluded cutting meat and dairy shrank a person’s carbon footprint by 73%, with a Vegan diet the ‘single biggest way’ to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and conserve natural resources, its impact ‘far bigger than cutting down on your flights or buying an electric car’. To many in Asia, this is a new Occident discovering ancient Oriental wisdom, where humans and animals are two parts of one organic whole which are meant to co-exist harmoniously. But co-existence with nature is valued in Eastern and Western civilizations: the issue is how to reconcile today their cultural differences.

Ancient wisdom on animal-human relations is important. As of old, mapping Asia can save lives. Cultural rocks beneath the surface shipwreck the reckless.

But first, a few pointers on ‘humans’ and ‘animals’ to set ancient Asian wisdom in a broader historical and intellectual context. Central to this are evolving functional relations between humans and their animal neighbours. Take the procurement and consumption of food, for example: from early Neolithic times, Homo Sapiens and his biological cousins used dogs in hunter-gathering; likewise, birds of prey and pigs (for truffles). Breeding boars for hunting failed, so pigs became primarily a source of meat. Over time, breeds of cattle, sheep and goats were similarly reared for meat and milk. The issue here is not so much the treatment of animals, but humanity’s dependence on them for food and flourishing.

An evolving, functional relationship can also be seen in humanity’s growing dependence on animals for travel, toil, and transportation of goods. The physical and mental faculties of donkeys, mules, horses, and bulls allowed them to become essential tools of human trades. Transport, tilling and travel all became easier. The expression ‘beasts of burden’ captures the ambiguity inherent here, with mutuality lost in functionality, creaturely independence sacrificed to the co-dependency of animals and humans.

The deep psychological bond, created over millennia, between animals and humans is hard to describe, let alone define scientifically. ‘Functionality’ is inadequate to describe the relationship between pets and their owners. Few question the positive role pets play in the life and health of their owners, and of other beneficiaries of their affection. Dogs no longer-scavengers, now faithful friends. Cats, shorn of all but a basic instinct to catch birds and vermin, the archetypal cohabitors of human space, free, fickle, opinionated and self-confidently adorable. Primitive ‘functions’ metamorphosed into the privileged life of a domestic pet.

Given the emergent bond between animals and humans, it is not surprising animals feature prominently in primitive iconography and ritual, in systems of power and morality. They are sacrificed to appease deities and elevated to divine status: their forms used to express ‘royal’ power, their qualities human ideals, the symbiotic relationship of humans and animals becoming alive with spirits, dread, and the grandest visions.

To map the rocks threatening cross-cultural E-W conversation about ecology and ‘animal rights’, we need to address relevant themes in Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism, Shintoism, and Asian expressions of the three Abrahamic religions, Christianity, Judaism and Islam.

i. Confucianism. Confucianism, despite its intellectual elusiveness, constitutes the dominant socio-political and moral system across ancient sinophone Asia. Throughout, it projected the priority of human life, ritual and morality onto the states and communities it inspired. Animals were aids to ritual and conduits of ‘heavenly order’ through a measured system of formalized sacrifices. Hence, animals become in classical Confucianism symbols of life sacrificed to, and regulated by, ‘the Way of Heaven’. In Confucius’s inversion of the ‘Golden Rule’, ‘Doctrine of the Mean’, and consistent appeal to leaders, officials, and citizens to conform life to ‘Heaven’s Will’ in order to secure ‘Heaven’s Mandate’, we catch glimpses of a vision for a harmonious, equitable, sustainable use of the world’s resources.

Confucius’s (551-479 BCE) heir, the ‘Second Sage’ Mencius (372-289 BCE), taught a more relational view of animals. They are to partake of the compassion owed to all. Hence, in a famous debate between Mencius and the King of Liang, the distress a buffalo feels in the face of slaughter is described; for, to Mencius, humans and non-human animals have feelings. That said, the priority Confucius and Mencius accord humanity’s quest to conform life consciously (qua morally) to the dictates of the heavenly ‘Dao’ (Lit. Way), rendered animals of secondary significance. Only humans could by default seek and find ‘the Way’. Recent moves to blur ‘animal’ and ‘human’ have no place here: empathy and inclusivity do not require identity.

That said, recent scholarship on animals in the Confucian world is illuminating. Three points stand out: i. Confucius has been shown to be sensitive to humanity’s co-existence with the natural world. Hence, he advocated bows and arrows (not nets) when hunting for birds: skill not voracity should shape his hunter’s art; ii. Confucianism is reserved about the slaughter of animals but respects the butcher’s profession. Confucian ritual set great store by the preparation and consumption of meals: propriety was at a premium. Which animals were killed, and in what manner, deeply mattered; iii. In Confucian culture, dog meat was – and is – acceptable (cf. Bao Er, ‘China’s Confucian Horses’, in Dalal & Taylor, Asian Perspectives on Human Ethics [2014], 73-92). Modern sensitivity to dogs as sentient pets – and widely reported atrocities in slaughterhouses – have impacted dog-eating in Confucian societies such as South Korea. In a recent on-line survey, 84% of Koreans said, ‘I have never consumed dog meat. I do not want to eat it.’ However, despite the potential implications of this attitude for the modern reception of Confucian values, meat is still a prominent feature of domestic and professional life in Confucian China, Korea and Japan. A sense that meat ‘fits’ and ‘empowers’ these enculturated rituals, remains strong. Blanket condemnation of meat-eating risks shipwreck on deep Asian cultural norms.

ii. Taoism and Buddhism. In contrast to Confucianism, Taoism teaches an alert respect for animals. A new syncretizing of Taoist philosophy and folk religion – and, with it, advocacy of monastic withdrawal to find ‘the Way’ – saw nature in all its forms revered. Hermits lived in the forests and mountains of East Asia to recover humanity’s primordial identity and proximity to nature. Martial arts linked to these ‘holy’ lives were patterned on the moves and survival strategies of cranes, tigers, monkeys, and mantises they observed.

Alongside this imitation of animal movement, Taoist tradition also celebrated animals as pets and fellow travelers on the path to enlightenment. In one story, a sage rises to Heaven with his dog, who has also eaten an ‘immortality pill’. In the ‘Butterfly Dream’ in the Zhuangzi, human-animal dichotomies are fluid and fallible Animal lovers note!

Traditional Taoist rituals also included consumption of meat. As Buddhist influence spread in Asia, vegetarianism became more popular with holy paper – even banknotes! – substituted for animal sacrifices. Over time, meat eating waned across sinophone SE Asia; notably in Singapore and Malaysia where the syncretizing of Buddhism and Taoism was pronounced.

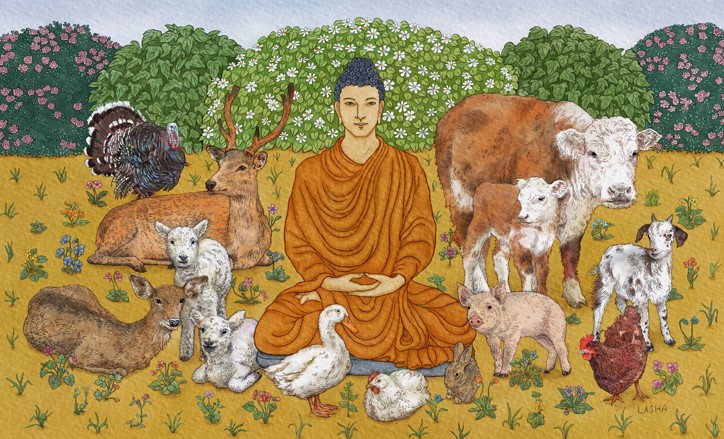

A parallel process of religious syncretism – and shared view that animals are metaphysically significant – is found in Buddhism and Hinduism. In both, re-incarnation in animal forms is a karmic possibility: respect for animals was a natural adjunct of piety. In some Hindu sects, vegetarianism was a logical conclusion, for others, an attractive option. That said, Hinduism and its doctrinal ‘offspring’ Buddhism, share acute awareness of sensory suffering. Pacifism, compassion, and respect for all living entities, are marks of the enlightened, their sympathy soothing anguish in individuals and the sensory world (cf. B. Finnigan, ‘Buddhism and Animal Ethics’, Philosophy Compass 12 (7), 2017: 1-12). We should not be surprised Buddhism found many kindred spirits at COP26.

Recent re-appropriation of Buddhist traditions in Asia and beyond are revealing. Moves to promote a meatless diet find philosophical and practical support. In South Korea, Buddhist temples both preserve and promote vegetarian traditions (cf. A. Shapiro, ‘Buddhist Diet for a Clear Mind’, NPR, 23 July 2015). Moreover, Taoism, Hinduism, and Buddhism unite in non-reductionist sympathy for non-human animals. Though oriental medicine prescribes animal parts as remedies, less careful symbolic acts of ‘life release’ (when large numbers of birds and other animals are released at one time) have had mixed success (cf. the release of 100s of rats by a Buddhist temple, Global Times, 19 January 2016)! Even in traditions known for their respect of animals, the temptation to grab a headline and weaponize creatures is strong. East and West are both guilty of this.

iii. Shinto (or Shintoism) is Japan’s indigenous religion. Its shamanic origins and respect for nature in totaliter, find counterparts in the popular spirituality of many NE Asian tribes (esp., in E. Russia, Manchuria and the Koreas). Unlike many mainstream religions, Shinto draws no sharp distinction between animate and inanimate realities. Rocks, rivers, and even manmade structure like bridges, can contain ‘Kami’ (Lit. spirit, avatar, or ‘god’). But foxes, snakes, or deer are also holy messengers from on High. Domestic animals can also share ‘Kami’ and have been venerated historically for this.

As with dogs in South Korea, modern Japanese culture has eroded historic Shinto norms and created hybrid attitudes towards animals, including domestic pets. Four points in relation to this deserve notice.

First, the default cultural attitude in Shintoism remains the potential of all animate and inanimate realities to carry ‘Kami’. The natural world in its entirety is thereby potentially divine and to be respected as such. Within this frame of reference, ecology is not so much a scientific discipline or political problem, it is a religious duty.

Second, while this general principle applies, other traditions create disruptive anomalies, which outsiders can find unintelligible or offensive. Deer, for example, are accorded special respect as messengers from above (N.B., during lockdown, the citizens of Nara celebrated their roaming wild; nippon.com, 19 August 2020). Foxes are similarly revered, particularly in fertility cults and worship of the sun goddess Amaterasu. More controversially to an ecologically sensitized world, whale hunting (inside and outside Japanese waters) is justified by politicians and self-interested businesses as ‘national culture’. Protection of endangered species is not, it seems, of greater weight than profit or politics, even when many Japanese do not now eat much whale meat. The disruptive impact of whaling on Shinto hegemony and Japanese ecology is clear, as is its dissent from new global norms.

Third, the historic fusing of animate and inanimate realities in classical Shinto tradition has exposed animals to new forms of physical and domestic abuse in modern, cartoon-loving, Japan. Animals in films, cartoons and computer games have become humanized. They speak and respond as humans. They are reimagined in suffering and death as humans, their divinity crushed by commerce. The consequence of this is that ancient tradition is lost in modern technology. The trivialized portrayal of animal abuse symbolizes cultural decay and scandalizes ‘animal rights’ activists. A culture that elevated non-human animals is now responsible for their undoing (cf. C. Atherton & G. Moore, ‘Speaking to animals’, Journal of contemporary Japanese studies 16. 1. Art. 1 [2016]).

Lastly, as we have glimpsed already, modern Japan contains an internal ‘clash of animal cultures’. Though Shintoism sees all creation as potentially godly, other traditional ‘lynchpins’ of Japan’s cultural identity give communities (such as whalers) and society at large an overarching sense of space and time. A dynamic vision of ‘tradition’ is not unique to Japan, of course, but in a Confucian-moral context it has a privileged role in shaping the present. As Romanian anthropologist Mircea Eliade (1907-1986) argued in The Myth of the Eternal Return (1949), tradition not only has the power to render the past present, it can also perpetuate abuse. It is for every society and individual within it to process the cost-benefits of cultural heritage (cf. G. Fung & A. Ka Hei Vu, ‘The Resilience of Japanese Whaling’ The Diplomat, 11 August 2021). Time will tell if, and how, Japan reconciles its religion, tradition/s, capitalist economics and modern appeals to ‘animal rights’.

iv. Asian expressions of the three Abrahamic faiths.Broadly speaking, Jews, Christians and Muslims in East Asia follow Genesis in subordination of animals to human needs and in their consequent respect for them. In this, moral criteria for human life extend to animals and the cosmos, as also divinely created (cf. Szucs, ‘Animal Welfare in Different Human Cultures’, Asian-Australasian Assn. of Animal Production Societies 25. 11 [2012]). Crucially, though Genesis teaches human ‘dominion’ over God’s creation (Gen 1.26-28), it does not sanction mindless destruction or prideful disrespect. Asian cultures impact the application of this scriptural construct. Three components warrant attention.

First, Islamic ‘taboos’ are evident in Malay, Thai and Indonesian culture. Traditional views of dogs as ‘unclean’ are pervasive. Evidence suggests, though, a growing number of Islamic individuals and families who have dogs as pets, that they see as ‘clean’ cohabitors of their home (cf. Illume Stories, ‘Exploring Pet Care Culture in Indonesia’, May 2021). Here is another example of animals prompting traditional faith to embrace new cultural values.

Second, cultural values can be remarkably resistant to change. ‘Unclean’ pigs are traditionally anathema to Islamic faith and diet, but they are popular livestock and a culinary delicacy in Buddhist Thailand. This has created long-standing tension, with one ancient Thai Muslim story depicting the pig as the dirty offspring of an elephant (an animal respected in Buddhism) that Satan impregnated on Noah’s ark (cf. A. Burr, ‘Pigs in Noah’s Ark’, Folklore 90. 2 [1979]: 178-185). Like Japan’s ‘tradition’ of mass whaling, pigs are a battle ground in the complex culture of Thailand.

Third, the socio-cultural impact of the three Abrahamic faiths in East Asia has always been muted. In part, this reflects the depth and tenacity of local traditions: it also testifies to the global consciousness evident in, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, in which local sensibilities are theologically relativized. That is, local views of animate and inanimate objects, that will one day be definitively assessed by God, can meanwhile be tolerated.

Looking ahead, it is unclear how East Asia will respond to on-going pressure on traditional views of animal-human identities and relationships. AI and genetic engineering pose new ethical and religious questions (cf. M. Roberts, ‘US Surgeons Test Pig Kidney Transplant in a Human’ BBC News, 21 October 2021). Religious connections between animals and human death – e.g., the role vultures in consuming corpses, or ‘towers of silence’, in Zoroastrianism (which connects Vedic and Abrahamic faith) – deserve further study. One thing is clear, rocks lie beneath the surface for any bold enough to venture into the fierce currents of Asian culture/s ancient and modern.

Dr Tomasz Sleziak – Research Associate