Olympic judges are a (usually!) friendly reminder of a serious truth: we live in critical times. From the Greek word krisis, judgments of every kind face our private lives and the global community. Unfriendly critics stalk our schools and universities, haunt the low dives of media manipulation, and enveigle their way into popular culture and the public square. Sometimes criticism brings a smile. Here’s A.A. Milne (1882-1956) in his delightfully astute children’s story Winnie the Pooh (1926), ‘“Piglet,” said Rabbit, taking out a pencil, and licking the end of it, “you haven’t any pluck.”’

Or what of poor Pot Noodle, who in April 2024 set aside ₤10,000 to award 100s of discontented customers ₤33 each for a ghastly image of an office worker consuming one of their pots … over-enthusiastically![1] Far more troublingly, government statistics on police complaints in England and Wales to the end of March 2023 record 51,605 complaints and 1jew20,243 allegations against 42,854 officers.[2] To say or do anything is now, it seems, to invite criticism. Is this new? No. In the early-18th century, the English essayist and critic Joseph Addison (1672-1719) was clear, ‘There is no defense against criticism except obscurity.’ Should we just roll over and accept what’s said fairly and unfairly about us? After all, too few of have what French moral philosopher Francois de la Rochefoucauld (1613-1680) called ‘the wisdom to prefer the criticism that would do them good to the praise that deceives them’. No, criticism stings and most of us try to give as good as we get! So, what can and should we do in these very critical times.

On a good day, friends who hold public office shrug their shoulders at the tirades of abuse they face on social media. ‘It goes with the job’, they point out, and international law rightly supports a person’s right to speak and criticize public officials.[3] Robust public debate and protection against defamation are both invaluable. As the Pan-African American sociologist and civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois (1868-1963) said, ‘The hushing of the criticism of honest opponents is a dangerous thing.’ And as US President Theodore (‘Teddy’) Roosevelt (1858-1919; Pres. 1901-1909) pointed out to colleagues, ‘To announce that there must be no criticism of the President … is morally treasonable to the American public.’ The strong, surprisingly sensitive, war-time Prime Minister Winston Churchill (1874-1965; PM. 1940-1945, 1951-1955) was similarly clear, ‘Criticism may not be agreeable, but it is necessary. It fulfils the same function as pain in the human body. It calls attention to an unhealthy state of things.’

That’s on a good day. On a bad day friends in the public eye wonder why they bother. At least, they are not alone. For it isn’t only Olympians who face judges: the actor and writer, surgeon and builder, teacher and travel agent, careworker and cleric – indeed, every citizen in a Western democracy – is now liable to face legitimate and illegitimate criticism for one thing or other.[4] But the novelist E.M. Forster (1879-1970) was surely still right, ‘[T]wo cheers for Democracy: one because it admits variety and two because it permits criticism.’ Truth be told, to some critics today their ‘right to criticise’ – and financial benefits that may accrue – is often as important as the truth of what they say. Here’s American sociologist, author and podcaster Brené Brown: ‘There are a million cheap seats in the world today filled with people who will never be brave with their lives but who will spend every ounce of energy they have hurling advice and judgment at those who dare greatly.’ Cheap seats with good views, it seems!

We live in critical times indeed. Perhaps most tragically of all, many of the crises the world faces are because we have forgotten the lost arts – and, indeed, our public, moral duty – of critical judgement and of criticising critics for failing to act responsibly. As Nobel Prize winning Nigerian author Wole Soyinka (b. 1934) warned, The greatest threat to freedom is the absence of criticism.’ Former US Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor (1930-2023; in office 1981-2006) refines this, ‘The freedom to criticize judges and other public officials is necessary to a vibrant democracy. The problem comes when healthy criticism is replaced with more destructive intimidation and sanctions.’ But what is ‘healthy’ criticism, and how might we encourage it?

One of the most important functions of Oxford House is to ensure ‘truth’ speaks to ‘power’, that analysis is accurate and unprejudiced, that reports are genuinely fair and balanced, that decisions are based on the global ‘common good’ not on narrow nationalist ideology. As such, Oxford House is a critical agency. It seeks to ask and answer the right questions in the right way for the right end/s. Naivety says this is easy: realism says it is incredibly hard. It is vital that as an organisation we have a good sense of the character, spirit and limit of our criticism. Inhabiting cultures in thrall to criticism and infested with critics would seem to leave little space or justification for adding another voice. Hence our role is, perhaps, better seen to be, as the great Anglo-American literary critic and poet T.S. Eliot (1888-1965) said of his eminent Victorian precursor Matthew Arnold (1822-1888), ‘a propagandist for criticism’. That is, to ensure the vital art of criticism is not demeaned by popular abuse or sophisticated hijacking. Will that be easy? Absolutely not, as Arnold himself discovered.[5]

T.S. Eliot and Matthew Arnold belong to a long history of reflection on the character and content ‘criticism’. Their focus was literature, faith and society, but the whole field of cultural, intellectual, artistic, political, scientific, humanitarian and religious endeavour is, and has been for centuries, subject to professional and amateur ‘criticism’. Indeed, the history, philosophy and diverse practice of ‘criticism’ reveal it to be a complex and important activity in every avenue of life. Failure to ask hard questions and/or acceptance of easy answers may satisfy short term but rarely produce lasting fruit. For it is truth, not convenience or bludgeoning, that liberates and lasts, leaving a legacy of health and harmony in individuals and communities. To be sure, if openness to truth signifies strength, suppresson of criticism is often a sign of weakness.

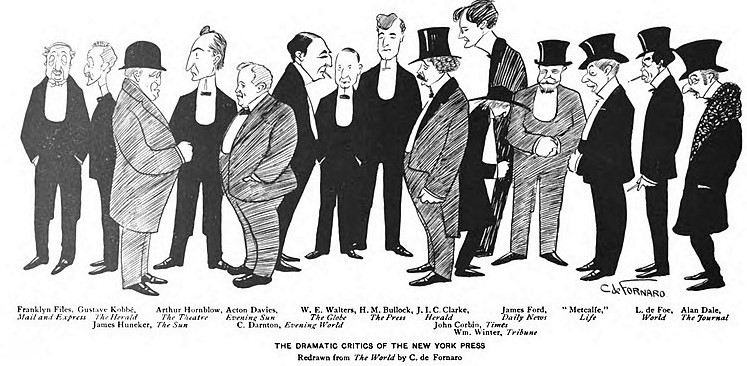

That said, the sour-faced theatre critic with his prejudiced eye, acidic spirit and sulphurous pen, is the stuff of popular films, novels and performers’ nightmares. Careers are made and lost on the say-so of an erstwhile ‘expert’s’ opinion. The acclaimed (but oddly short-lived) sitcom series The Critic (1994-5), an animated adult counterpart to the satirical children’s The Simpsons, and the September 2024 release of Anand Tucker’s dark thriller The Critic,starring Sir Ian McKellen and Gemma Arterton, suggest the often cryptic world of critical reviews is rich in creative possibilities and dark manoeuvers. Indeed, to Matthew Arnold it was criticism’s power to stimulate creativity that justified its existence and its careful use. But, as Arnold knew well, it isn’t easy to talk about ‘criticism’ without provoking it, nor easy to complain about ‘critics’ without becoming one! We may eschew caricatures of careless, caustic criticism and aspire to the heights of a well-informed literary or theatre critic, but neither is easy. Personality and principle shape critical faculties just as much as taste diet and habit daily life. Woe betide us if we think (our) criticism invariably fair!

Following T.S. Eliot’s assessment of Matthew Arnold, the question we should perhaps be asking is not How do we stop all this criticism? but, What could and should a thoughtful ‘propagandist for criticism’ say today? In other words, on what basis might the worthy task of ‘criticism’ per se be rescued from mindless popular abuse and obscurantist academic deconstruction?[6] In answer, I suggest five key principles be borne in mind, each of which offer criteria to assess the legitimacy of (our) criticism and inform Oxford House’s constructive critical role of ‘speaking truth to power’.

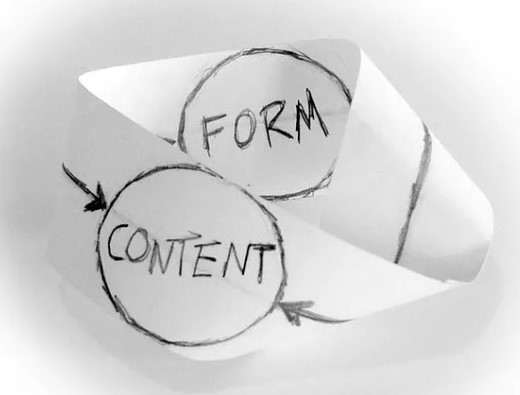

First, legitimate criticism will balance attention to ‘form’ and ‘content’. It won’t only focus on what is said, but how something is said. High-level literary criticism has always adopted this biopic approach; so a text is analysed and ultimately acclaimed (or critiqued) for the creativity of its approach to characters, setting, plot and theme. Rubbishing a book simply for its story line is, then, as ill-advised as commending a work just for its vocabulary! Taken to a higher level, classical poetry was expected to conform to literary (i.e. rhythmic) ‘codes of conduct’[7] while capturing fleeting images in words and evanescent feelings in syllables or silence. Film and theatre critics today have their own spoken and unspoken expectations of what makes for a ‘good show’ or an ‘Oscar-worthy’ performance. When those expectations are (for whatever reason) at the expense of balance and elevate ‘form’ or ‘content’, we can, and should, criticize the critic for imbalance. Why? Because they have failed to read and reflect how the author of a ‘piece’ (viz. film, novel, poem, portrait, etc) has structured the relationship between what they’ve tried to ‘say’ and how they’ve tried to ‘say’ it. Criticism shouldn’t blur those distinctions, but instead carefully exegete them. As the writer, critic and public intellectual Susan Sontag (1933-2014) argued, ‘The aim of all commentary on art now should be to make works of art – and, by analogy, our own experience – more, rather than less, real to us. The function of criticism should be to show how it is what it is, even that it is what it is, rather than to show what it means.’

So, what’s the relevance of this for our critical society and for a critical time globally? And, as importantly, what does it say to those who aspire to ‘speak truth to power’? Two things, I suggest. First, much mouthing off in social media should be ignored. Why? Because it tends to focus on‘form’ or ‘content’, and rarely on both together. So the young actor is vilified for her looks or her portrayal of a character, and too rarely for how through both together she plays her part. Likewise, political criticism in image-driven societies tends to comment on a leader’s age or their policies, rarely on how their identity shapes those policies. Healthy criticism will avoid this bifurcation to penetrate image and cross-examine motivation. Those who seek to ‘speak truth to power’ must do the same: then their analysis will resonate with reality and accurately engage with the ‘form’ of problems and the ‘content’ of possible solutions. Second, sensitivity to ‘form’ and ‘content’ – and, crucially, their relationship – helps a thoughtful social critic ask more searching questions and give more rounded answers. Too often communities are commended or condemned for the ‘form’ of their life more than the ‘soul’ that inspires them. When this happens ‘poverty’ and ‘riches’ are defined in financial terms and ‘happiness’ and ‘health’ reduced to material goods. No, responsible government, like a good film or book, will take a holistic view of human flourishing and resist the seduction of soundbytes and journalistic simplification.

Second, as an extension and clarification of this, healthy criticism will (aim to) balance objectivity and subjectivity. It will resist a quick judgment based on either facts or feelings. Empirical evidence and human experience will both play their part. This will not sit easily with those who prioritise their ‘feelings’ or ‘human experience’. It will also rattle the politician or statistician who expects data to win every argument! No, as the long history of literary criticism reveals, the value of a poem or other piece of literature is ultimately determined by critical faculties that are sharpened by exposure to great literary ‘classics’ and refined by sensitivity to human emotion (or, as it is often and more generally defined, the ‘affections’). This is too rarely the case. As the young American poet Sylvia Plath (1932-1963) complained, ‘It seems this is an age of clever critics who keep bewailing the fact that there are no works worthy of criticism.’

Applied to current global crises, ‘truth’ will seek to challenge ‘power’ to look beyond mere economics, perception, statistics or military capability, to consider what is also ‘good’ and ‘right’; that is, what is humanly acceptable and morally justifiable. It will go beneath the surface of data to discern and decide in light of the deeper realities of ‘ought’, ‘must’ and ‘maybe’. By definition ‘subjectivity’ admits the limits of human judgment and provisionality of human feeling. For, just as no individual’s subjectivity speaks for all, so no single fact is ever a silver bullet solution to a complex problem. Healthy criticism knows how to negotiate the (objective) rocks and (subjective) eddies in the swirling torrent of daily life and international diplomacy. It will also criticize critics of ‘facts’ and ‘feelings’ for their failure to see that both have their place in informing the way ‘truth’ is discovered and ‘power’ directed.

Third, healthy criticism will balance history and modernity. It will make judgments against ‘the long view’and resist enslavement to the past in order to safeguard the ‘here and now’. Sadly, this ideal – indeed, ‘balance’ itself! – is particularly unpopular today, with ‘criticism’ frequently a mask for extremism and ‘critics’ clothed in self-justifying moralism. As the American journalist, critic and satirical social commentator H.L. Mencken (1880-1956) wryly observed, ‘Criticism is prejudice made plausible.’ How very – and dangerously – true! Loss of an historical perspective on current issues plays into the hands of progressives. The reverse is also true: a mindless, populist appeal to an idealized past to justify a ruthless modern agenda (as Putin does in Russia and Modi in India) wrongly empowers what ‘is’ by an erroneous and manipulative appeal to what ‘was’. Preserving a two-way dialogue between ‘now’ and ‘then’ is vital. So, critics of modern schooling are wrong when they resist curricula development and idealise past methods. No reader of either Arnold would find support for that! Critics of past history are equally wrong for condemning previous generations simply because, ‘They’ didn’t do what we would have done and now want and believe.’ No, standards change. Lessons are learned. Life moves on. History has always been a good foil for modern error. Modernity has always been a right source of questions for which history offers some of the answers we seek and need.

Applied to the issue of ‘speaking truth to power’, balancing ‘history’ and ‘modernity’ affords a way out of the dry dictates of ‘duty’ and ‘tradition’ and crippling constraints of pragmatism and ancient practice. As we noted already, Matthew Arnold was a powerful advocate for the creative potential of ‘criticism’. He was willing to be unpopular – an ‘elegant Jeremiah’ one contemporary journalist called him – to disrupt what he saw as the presumptuous ‘barbarism’ of the aristocracy, the mindless ‘philistinism’ of the materialist middle class, and the patronised ignorance of the working class ‘populace’. No section of society was safe from his scathing satire; least of all, perhaps, ‘the portly jeweller from Cheapside’[8] whose self-interested horizon and low, uncritical, democratized, view of ‘popular culture’ were satisfied with the status quo … as long as the money kept coming in. ‘Truth’ asks ‘power’ if it is willing to take less trodden paths, risk unpopularity and challenge popular shibboleths for the sake of historically rooted culture and freedom from the constraints of low expectation and (supposedly) unsolvable social and diplomatic crises. Criticize critics of ‘trying something new’, ‘pushing out the boat’, ‘playing safe’? Yes, absolutely.

Fourth, healthy criticism will balance individuality and morality. Too often a false dichotomy is drawn between me and thee, between what is good for the individual and what benefits all. Hence, much popular criticism takes the high road of ‘my rights’ and ‘my life’ to pour venomous scorn on others for their failure to ‘love’ or ‘respect’ or ‘understand’. The imperialist, individualist, ‘I’ expects all to kowtow. If not this, then the opposite. Here the corporate ‘we’ of ‘every one says’, and ‘no-one now doubts’, and ‘science has proved’, lays claim to a public moral preeminence which leaves no room for doubt or questioning. This is a strange perversion of the legitimate act of ‘criticism’ in which – as critics of literature, film, art and music consistently demonstrate – diversity of opinion is the norm and failure to dissent plain weakness. But – and this is my point – legitimate criticism supports my right to say what I think and asserts my public moral duty to protect my neighbour’s right to do the same. It is a strange, stifling, society that fails to make space for moral criticism and private judgment. It is also a dark and dangerously oppressive culture that imposes moral decisions on all its citizens and denies them a right to choose. Balanced criticism will be sensitive to the dangers of folding me into we and projecting onto me the values we purportedly now hold. Liberal democracies become illiberal when they commit either of those ideological crimes!

Heightened sensitivity to the importance of naming and balancing appeals to ‘individuality’ and ‘morality’ is an essential element in ‘speaking truth to power’. Government pressure on citizens to conform now becomes as questionable as selfish claims by ‘interest groups’ that their ‘right’ to set the agenda and change the law cannot be questioned. Similarly, democracies that claim to protect their citizens ‘rights’ while enshrining in law moral codes that offend religious groups have blurred the distinction, and failed to safeguard the difference, between ‘individuality’ and ‘morality’. How crisp, clear, and challenging international relations become when moral criteria are introduced into policy making and international diplomacy. Yes, advocates of such may be – no, will be! – criticized for such. Good – if it rescues decision-making for dull conformity and persuades a diplomat or government official on moral grounds not to do their professional duty.

Lastly, healthy criticism will balance humility and confidence. It will be neither swift to judge nor slow to comment, claiming a right to speak and readiness to admit it may be wrong. This kind of honesty and flexibility is rarely the norm in western societies today; humility being an elusive quality and confidence an esteemed virtue. As playwright, physician and novelist W. Somerset Maughan (1874-1965) observed, ‘People ask for criticism, but they only want praise’! Healthy criticism per se is always associated with ethics. It feeds off the distinction between ‘the good’ and ‘the best’. Even perverted forms of popular criticism make moral judgments to name and shame offenders.

Writers on ‘the ethics of criticism’ have consistently highlighted the social and moral context of criticism, and their place in determining what is and isn’t deemed acceptable. As one recent study notes,

The ethics of criticism involves critics in the process of making decisions and of studying how these choices affect the lives of fellow critics, writers, students, and readers as well as our ways of defining literature and human nature. … To criticize ethically brings the critic into a special field of action: the field of human conduct and belief concerning the human.[9]

Matthew Arnold has often been criticized for the ‘elitism’ of his social and literary judgments. He heeded the accusation (indeed, felt it deeply), but he did not allow this to divert him from his higher purpose of rescuing ‘culture’ from popular oblivion and elevating ‘criticism’ per se through exposure to the fresh air of informed analysis and genuine freedom of speech. He may not be the best example of a ‘propagandist for criticism’, especially if his ideas are transfered to the realm of public policy and Internation Relations, but he does what we should all want a good friend to do, he asks hard questions and won’t settle for trite answers.

Getting the balance right between humility and confidence, especially when an amateur challenges a professional or an inquirer a seasoned expert, is always going to be hard. Better to fail in that endeavour, I would argue, than to become yet another ‘portly jeweller from Cheapside’. But the last word to two people Arnold valued highly, to Jesus of Nazareth for his sober warning ‘Judge not that you be not judged’ (Matthew 7. 1) and to the German poet, literary critic and friend, Heinrich Heine (1797-1856), ‘He only profits from praise who values criticism.’

Professor Christopher Hancock – Director

As in all Oxford House Briefings, every effort is made to attribute images where information is available.

[1] Cf. https://www.getreading.co.uk/whats-on/food-drink-news/pot-noodle-offering-33-compensation-28969056; accessed 30 July 2024.

[2] In addition, there were 2,773 conduct cases and 5,363 allegations against 3,188 officers, and no fewer than 1,169 recordable conduct cases and 2,402 allegations involving 1,316 officers: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/police-misconduct-england-and-wales-year-ending-31-march-2023/police-misconduct-england-and-wales-year-ending-31-march-2023; accessed 30 July 2024.

[3] On this, see https://aceproject.org/main/english/me/mea01i.htm; accessed 30 July 2024.

[4] Cf. In China under President Xi Jinping (b. 1953), to be ‘criticized’ is, as during the first Cultural Revolution (1966-76), to face social and political censure (or worse) for deviation from government policy and ideology.

[5] For an interesting modern biography of Arnold, see N. Murray, A Life of Matthew Arnold (Hodder & Stoughton: London, 1996). Arnold established himself first as a poet (N.B. he was employed throughout his life as a Schools’ Inspector) before progressing to prose commentary on literature and Victorian society. Arnold was son of the famous educational reformer and historian Dr. Thomas Arnold (1795-1842), who was Headmaster of Rugby School from 1828-1841 and Regius Professor of Modern History at Oxford University from 1841-2.

[6] Cf. Recent critical theory – notably that of the French philosopher, historian, literary critic and political activist Michel Foucault [1926-1984] – has subordinated the reading and writing ‘self’ to the structure and power of language and linguistic structures. Defining a text’s ‘meaning’ becomes, thereby, not only negotiable but virtually impossible – or so some literary critics confidently (and thus illogically!) claim.

[7] Arnold was Professor of Poetry at Oxford from 1857-1867. The role required he deliver a limited number of public lectures. Sensitive to the history of literary criticism, in a famous series on translating the 8th-century BCE Greek poet Homer, Arnold memorably commended Homer’s ‘grand style’, by which he meant Homer’s rapid, clear, succinct flowing language and that his poetry ‘can form the character, it is edifying’.

[8] Cheapside was, and still is, in the heart of the financial district in the City of London.

[9] Cf. T. Siebers, The Ethics of Criticism (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018), 1: Project MUSE, https://doi.org/10.1353/book.58012; accessed 29 July 2024.