In 1997, I was living and working in Tanzania. The General Election held in the UK on May 1 of that year saw the scandal-ridden Conservative party (led by John Major) blown out of office by the fresh winds of Tony Blair and the ‘New Labour’ party, who promised change, devolution, fiscal responsibility and more female representation. It was one of the largest electoral defeats in British history. Major stepped down as leader of the Conservative Party shortly afterwards. The day after the election, a senior Tanzanian colleague said to me how astonished and impressed he was at the smooth handover of power, at the graceful way in which Major moved from being Prime Minister to Leader of the Opposition.

My time in Parliament (as MP for Stafford from 2010-19) confirmed my sense that the most important position in British politics after the Prime Minister is not the Chancellor of the Exchequer or the Foreign Secretary, but that occupied by the person on the green front bench opposite the Prime Minister in the House of Commons, namely, ‘the Leader of her Majesty’s Most Loyal Opposition’, to give the position its full title.

The title ‘Leader of the Opposition’ is commonplace in legislatures around the world; that is, outside the fortunately limited number of ‘one-party’ states. It is never an easy job. The official title of the position in the UK recognises two important and distinctive characteristics, namely, that the Opposition is ‘Her Majesty’s and that it is ‘Loyal’. Both the Government (N.B. it is ‘Her Majesty’s Government’) and the Opposition ‘belong’ to the Crown and are of equal significance … if not of equal political weight. The monarch must not, and does not, show political or positional preference. This is crucial.

But there is an obligation on both sides of Parliament, too – they must be ‘loyal’ to the monarch, that is to the Crown (as the ultimate defender, representative and guardian of all the people of the United Kingdom), and to the people of Britain.

With notable (and all too occasional) exceptions, recent Leaders of the Opposition of both main parties in the UK have, in my view, not taken their position with sufficient seriousness. They have seen it as either a stepping-stone to power or, after defeat in a General Election, as a role to be vacated hastily, even when urged by their party to stay.

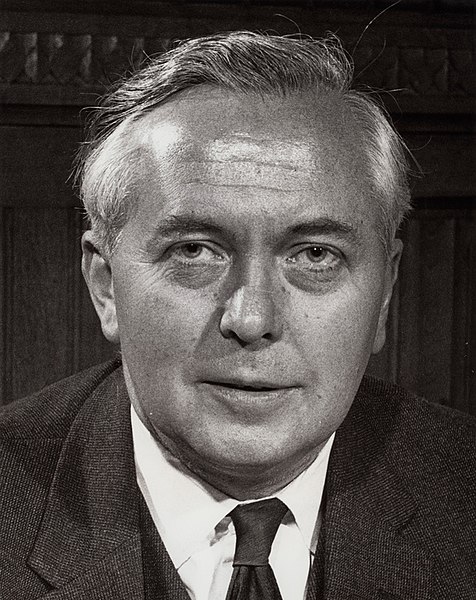

The last Prime Minister to be defeated in a General Election (1970) and stay on for more than a year as Leader of the Opposition was the doughty Labour politician Harold Wilson (1916-95; PM 1964-70, 1974-76). Wilson became Prime Minister again in 1974. The same was true of Britain’s War-time Prime Minister Winston Churchill (1874-1965; PM 1940-45, 1951-55) who spent 6 years as Leader of the Opposition after losing the 1945 General Election. Like Wilson, Churchill became Prime Minister again (in 1951).

Modern politicians and political parties do not, I believe, recognize, as Churchill and Wilson did, the importance of the role of ‘Leader of the Opposition’. The fact that the position was held by previous Prime Ministers enhanced the dignity of the position. In recent times, defeat at a General Election has more often been seen as signalling the end of a political career rather than the start of an important role in the democratic process. The UK – indeed, every country – needs people of experience and talent in Opposition.

So, how might the importance of the ‘Leader of the [Her Majesty’s] Opposition’ be seen? And what lessons can be learned about ‘Opposition’ per se?

First, the Leader of the Opposition is a voice for all who did not choose the governing party or coalition. Statistics reveal that in the UK the government normally has the support of only a minority of those voting (and, thus, a minority of the electorate). For much of the time, the Leader of the Opposition speaks – and must speak – for, or on behalf of, the majority in the country. This should never be forgotten or undervalued. The voice of Opposition is vital.

Second, the Leader of the Opposition must be strong and effective enough to ensure that those who dislike or disagree with a Government’s policies are confident their voice and views are clearly and consistently represented in Parliament. In doing so, the Leader of the Opposition has a key role to play directly and indirectly in the preservation of social harmony and in minimising the risks of civil disorder. S/he must give people hope that, even if the Government does not listen now, that may change through argument and/or at the next General Election. A weak Leader of the Opposition damages the country and its democracy. Ineffectiveness in Parliament sends a message to the discontented in the country at large that Parliament itself is weak, deaf or unconcerned. Protest, apathy, and a sense of political disenfranchisement grow when a Government is not held to account by effective criticism and a respected leader of ‘Her Majesty’s Opposition’.

‘The duty of an Opposition is to oppose’

Lord Randolph Churchill, 1849-95

Third – and this may sound strange – a Leader of the Opposition must love their country and be ‘loyal’ to it. That does not mean he or she is uncritical of the Government: quite the opposite, in fact. But the Government is not the country. Britain’s post-War Labour Prime Minister Clement Attlee (1883-1967; PM 1945-51) – who, incidentally, was leader of the Opposition on no fewer than three occasions – was seen as a ‘no hoper’ by outsiders in the run up to the General Election in 1945. In the event, he won a landslide victory over Churchill. Why did he win? The country was desperate for fairer policies after the World War II. Many voters reacted badly to Churchill’s claim in a campaign speech in June 1945 that Labour would need ‘some kind of Gestapo to implement their policies’. In contrast, people saw the Opposition leader Clement Attlee as a loyal, public servant, who had served his country with bravery and conviction (and been wounded) in the First World War. It was the country that voted him in – and voted Churchill out.

Finally, a Leader of the Opposition is to embody what one might call ‘Losers’ Consent’, especially when an election has been close. A free and democratic society depends on the government recognising that it has a duty to care for the whole nation – and not just its supporters. It also depends on the Opposition accepting defeat and recognising the elected government’s mandate to govern.

Constituents whom I showed around Parliament occasionally described it as merely a ‘talking shop’. They were surprised when I agreed with them! But I also pointed out that Parliament is meant to be a talking shop. The clue is in the name. And a parliamentary talking shop is a vast improvement on the civil wars that racked Britain in the 13th, 15th and 17th centuries! As Churchill famously said in another context ‘meeting jaw to jaw is better than war’ (sic). The aisles and benches of the two Houses of Parliament are the verbal battleground on which conflict should occur (far better there than on the streets outside) and should also be resolved. When Parliament became stronger – after the passage of the Bill of Rights (1689) and emergence of Britain’s first de facto ‘Prime Minister’, Robert Walpole (1676-1745), in 1721 – the potential for civil conflict lessened. Parliament may appear to cause conflict: we should never forget its role as an instrument of reconciliation. The Leader of the Opposition has a mandate to call the Government to account and to ensure peace is preserved across the land. When Britain, the oldest democracy, fails to model this many lose out around the world.

Parliament can only be effective when there is a strong, ably led, Opposition. This is a lesson some countries (even those with some a form of parliamentary democracy) are yet to learn. In many contexts, the Leader of the Opposition has a dangerous job. His or her position is not seen as integral to good government nor as a vital, constitutional defence of institutional integrity and legitimate dissent. Rather leaders and members of Opposition parties are cast as enemies of the government and state, and tantamount to traitors. There is here no acknowledgement that you can be loyal to your country and opposed to the policies of its government. One Leader of the Opposition whom I know personally has been arrested and imprisoned several times, usually on flimsy grounds.

Political success, in the world’s terms, means winning and gaining power. You are either just a ‘winner’ or a ‘loser’. The dignity accorded the position of ‘Leader of Her Majesty’s Most Loyal Opposition’ wisely contradicts this. Defeat in an election does not mean that you are a ‘loser’. It marks the beginning of a different, vital, role which is of fundamental importance in a free country. The true mark of a stateman or stateswoman is that they serve their country and party in this role with the same energy, commitment, and grace they would show as Head of State or Leader of the Government.