I am delighted to introduce Dr. Mark Hijleh to you as the author of this week’s Oxford House ‘Weekly Briefing’. Mark is Provost of The King’s College, New York and an Associate of Oxford House, specialising in music and culture. With degrees from John Hopkins University, the University of Sheffield (UK), Ithaca College and William Jewell College, Mark is an accomplished theoretician and practitioner of music. His publications include The Music of Jesus: From Composition to Koinonia (2001), Towards a Global Music Theory (2012), and Towards a Global Music History (2018). His theme this week connects with Oxford House’s current ‘Music & Diplomacy’ initiative, which addresses music’s power to nurture intercultural harmony and the needs young professional musician’s face in the current COVID crisis.

The soliloquy by the love-struck Orsino, Duke of Illyria, that introduces Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night presents, on first inspection, a predictably shallow perspective on love. Love as the fruit and passion of Queen Eros (sexual love). Here is Orsino’s fanfare to the object of his love, the Countess Olivia:

O spirit of love! how quick and fresh art thou,

That, notwithstanding thy capacity

Receiveth as the sea, nought enters there,

Of what validity and pitch soe’er,

But falls into abatement and low price,

Even in a minute: so full of shapes is fancy

That it alone is high fantastical.

Love is presented here as a spirit ‘quick and fresh’ that possesses a boundless capacity, like a mighty sea. But what if we read the Duke’s words as a subtle commentary on other forms of love? Perhaps Shakespeare intended that, using a double entendre about fickle passion to commend something else. What other forms of love, we might ask, did Shakespeare intend to reference when he spoke of the ‘music of love’? What other ‘capacity’ does it possess that can move humans deeply?

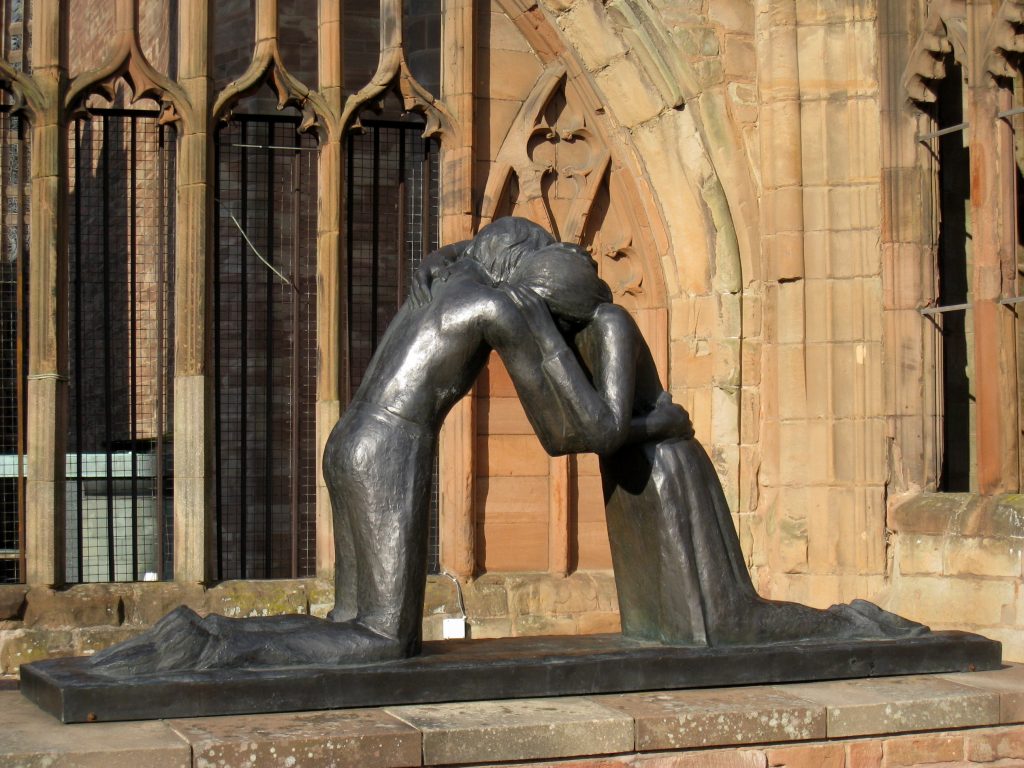

To my mind, the music of love-as-reconciliation possesses a similarly boundless ‘capacity’. Rightly interpreted, reconciliation is, like music, more than the merely ‘fantastical’ trifle some dismiss it as cynically. As the South African ‘Truth and Reconciliation Commission’ (fr. 1996) so vividly reminded the world: reconciliation has the power to heal. It sings an insuppressible song of hope to souls languishing in grief and despair. If music be the food of that love ‘play on’ indeed.

So, perhaps Shakespeare is talking as much about music as he is about love in the soliloquy at the beginning of Twelfth Night. After all, as Confucius claimed: ‘Music produces a kind of pleasure which human nature cannot do without.’ So, when erotic love ‘falls into abatement and low price’, is music for Shakespeare the constant ‘human nature cannot do without’, the key to ‘capacities’ in love that love forgets? After all, no human culture – even those without language – is without some form of ‘music’. It is a universal language and human constant; as fundamental a feature of humanity, we might say, as love and a longing for intimacy. It is more than an occasional need or accidental cultural construct (although, of course, musical styles may be culturally constructed), it is a ‘spirit’ with its own primordial ‘capacity’. As the American poet American Poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-82) saw, ‘Music is the universal language of mankind.’

If music is envisaged by Shakespeare to be linked with love in a broader sense than merely Eros, how else are these other forms of ‘love’ expressed? We have touched on reconciliation already. We should look for music’s impact on other forms of love-in-relation, perhaps even as a corrective to human relations. The atheistic German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), for whom hope along with faith dissipated amid anger, depression, madness, and despair, maintained ‘without music, life would be a mistake’. Music reached into his darkness in ways faith and love never could. The first relationship music often addresses is the relationship a person has with themselves. It enables healthy self-love and self-esteem.

So, what would constitute a ‘mistaken’ life? Not just a life without music; but, surely, as Shakespeare saw, a life without love’s boundless capacity – and, we might add, a spirit of freedom through reconciliation, of harmony in relationships, of peace in the soul.

The need for functioning human relations has never been greater in our tense, complex, multi-cultural 21st-century world. In the face of this, love, like music, need not – indeed, cannot and should not – be subject to a cultural straight-jacket. To the degree that human relations are culture specific and culturally conditioned, custom and style have a hugely important role to play. But what of the culturally unbounded human relations that we encounter with ever-increasing relevance in our globalized world? If the spirit of love is ‘quick and fresh’ and music feeds that love, why do we see such defensiveness about our cultural distinctives and slowness to accept cultural diversity? Following Shakespeare, we might perhaps wonder if the boundless, global gift of music cannot enable a transcendence of our limited loves and enrich our capacity to accept ‘the other’.

As a musician, I am fascinated not only by the universal phenomenon of music (see the recent Harvard study: https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2019/11/new-harvard-study-establishes-music-is-universal), but also by its relationship to ‘ritual’ and essential ‘character’ (viz. what kind of thing is music really?). Three things stand out for me as we look with Shakespeare at the light music sheds on love and love sheds on music.

First, the universality and yet diversity of music as a global, human phenomenon, suggest music’s meaning – like love itself, we might say – is not easily discerned. It possesses an inherently elusive nature and complex character (again, like love). Just as ritual speaks beyond what is signified, so music connotes meaning beyond and through sounds. Like a sacrament, it signifies more than is seen. When paralleled with music, love is also, then, as Shakespeare saw possessed of ‘capacity’ beyond the immediate. Why is music so powerful to a Nietzsche? Because it does so much more.

Secondly, music, like love and life, is about a series of encounters. As such, we might say, music is inherently relational. But, just as we do not enter (even casual) relationships without some kind of ‘expectation’, so discerning music’s meaning involves a balancing of expectations that are either intuited psychologically or pre-programmed culturally. In his study Emotion and Meaning in Music (1956), American musicologist Leonard Meyer (1918-2007) maintained discernment of musical ‘styles’ is all about the fulfilment or thwarting of expectations. Culture and personality impact on those expectations. The nature and forms of love are not immune to cultural, psychological, and relational expectations. The ways we encounter, and express love will differ. Shakespeare is surely right, there are many forms of the ‘music of love’ and,we might add, of a love for music!

Thirdly, music – again like love, I suggest – has an essentially transcendent quality; that is, though expressed in forms (often linked to patterned rituals) and discernible by scientific analysis (viz. the physics of sound and the response of the human brain), there is always a more to the human experience of music. Its meaning resides, like a tide, in the ebb and flow of notes and thoughts, sounds and images, ideas and feelings, heart and mind and soul. It is not surprising music is a universal phenomenon, so is religion – and so is love and the need for reconciliation. To quote (and parody) the English poet John Donne (1572-1631), music has the capacity to ‘batter the heart’ with existential realities that transcend speech. If we wonder why we are moved by music – moved even, perhaps, to confront our flawed human tendency to division and accusation, resentment and bitterness – then it is, surely, because music has again disclosed its ‘capacity’ to speak love to us in new ways.

What role does music really play in our world? To confront and to unite it in new ways. To Confucius, again (pace ancient Greek philosophy): ‘If one should desire to know whether a kingdom is well governed, if its morals are good or bad, the quality of its music will furnish the answer.’ Music has transformative, revelatory potential, as Shakespeare’s Duke Orsino knew. It can make the nature of love clearer: it can make the need for and beauty of love-in-reconciliation that much more remarkable. Has music a key role to play in Oxford House? Absolutely! Play on, then! Not because music may satiate or distract from the pains of life (including our fickleness), but because it empowers reconcilers and enables reconciliation. Thankfully, as a Latin American proverb declares: ‘A good guitarist will play on one string … (but) God writes on crooked lines.’

Mark Hijleh, Associate