Students of Korean culture (North and South) immerse themselves in the history, tradition and philosophy of the last, great Confucian dynasty, the Joseon, or Chosun (1392-1910). Founded in 1392 by Yi Seong-gye (later Yi Dan), for five hundred years Joseon rulers led Korea in its embrace of Confucian – especially Neo-Confucian – culture, thought and ritual. The legacy of that tradition lingers in both Juche (North Korean) socialism and in the pro-Western capitalism of the democratic Republic of (South) Korea. In this Briefing I look at the nature, and lingering impact of Joseon culture on the Korean peninsula, for the light this sheds on the political ethos and societal structure of the Koreas today.

First, a word on rulers and ruled in the Joseon era. Study of classic resources from this period would suggest, superficially at least, that Korean culture was determined either by high-born, highbrow ruling elites or social riff raff, who would habitually sell their wares to the highest bidder. In contrast, the middle strata of society – clerks, soldiers and farmers – are usually seen as dull, culturally marginal, and fast bound by tradition and law to their life of ‘virtue’, duty and willing preservation of the socio-political and economic status quo. Such changes as the middle orders saw were the product of legal revision or business acumen; but they were debarred from politics and despised by the ruling Confucian literati. As in China, Korean Confucianism actively promoted disciplined self-improvement, but Korea was never a meritocracy, and social ‘equality’, as we understand it, was proscribed by law, habit and inherited custom. My doctoral study began from this premise: over time, I saw a marked discrepancy between ‘class-based’ and ‘status-based’ mobility in Joseon society.

The European Enlightenment taught the West to see Confucianism as embalming Asia in a stiff, deathly, cultural shroud, with movement and change all but impossible. Closer study shows Korean Confucian values – which scorned profit-making by its elites – didn’t so much ossify society as obliterate upward, status-based mobility and facilitate a downward energy that increased late-Joseon social stratification, fragmentation and resentment of hierarchy. Enterprise, corruption, and an open system of military examinations allowed some to buck social trends and cultural norms, but the Confucian status quo was remarkably durable. Confucianism is here less an instrument of cohesion as of societal alienation. In other words, the seeds of recent Korean history are sown in the rich soil of its ancient Confucian culture.

Read in this light, North and South Korea represent two quite different, but now plausible, evolutions of their shared Confucian heritage. Both countries embrace an inclusivist vision of Korean life; one in the form of collectivist Juche socialism, the other universal franchise. But, and this is important, following the critical theory of German social philosopher Jürgen Habermas (b. 1929), the extent of a group or community’s place and activity in the ‘public square’ is driven not so much by natural desire as a nurtured disposition that is acquired in homes, jobs, schools, and other places of learning, and is then subsequently safeguarded by law, or enshrined in cultural habits. Far from instilling equality and freedom, and opening access to all on grounds of ability and achievement, most societies and political systems – including the Koreas – suppress self-expression via doctrinaire pragmatics or subliminal expectation. This is certainly true when we look at the impact of Confucianism on Korean culture and politics.

North and South Korea are united in their connection with Cheng-Zhu Neo-Confucianism; that is, the school of rationalist Confucian thought traceable to scholars Cheng Yi (1033-1107), Cheng Hao (1032-1085) and, perhaps especially, the influential Zhu Xi (1130-1200). In both Koreas, it is this traditional system that determined Joseon daily life. This heritage inspires the stratification and attitude towards social mobility found across the Korean peninsula today; that is, it helps to explain and sustain a Korean resistance to change, and will to challenge past and present socio-political and economic realities (good and bad).

A few specific examples of the impact of Cheng-Zhu Neo-Confucianism on North and South Korea today will, I hope, help to bring the reality of this inbuilt cultural mindset into focus.

First, Korean attitudes towards profit. Juche Socialism extracted from Korean tradition a negative view of personal gain. When the founder and former premier of North Korea Kim Il-Sung (1912-1994) prioritised the ‘collective good’ and the redistribution of income and produce, he was not fundamentally contradicting Korean Confucian culture. The resultant ostracism of independent businesses (until the 1990s) was perceived to be less oppressive than outsiders might imagine. Likewise, the classification system in the new Workers Party of Korea, which introduced mutual assessment and evaluation of state loyalty as criteria for benefits or punishments, resonated with Confucian Korean social stratification. Seen in this light, and with money and taxes of less relevance to the majority than the state-controlled allotment of goods, private enterprise (even when successful) made little, if any, difference to a person’s life. Why? Real rewards were reserved for the officially loyal. More recently, increased dysfunction in North Korea’s economy and polity have fractured the direct link between loyalty and prosperity and opened new avenues for entrepreneurs. Meanwhile, those who out of fear or tradition accept the status quo are (mostly) safe and (very) poor.

In the South, the dominance of Chaebol family conglomerates (built over Confucian clans and Japanese infrastructure) roughly parallels central planning in the North: indeed, the economy and politics of society in the South are profoundly shaped by these vast bodies. Millions depend on them for life and limb. But, and this is the point, these corporations also act to prolong Korea’s traditional societal stratification and pressure toward downward mobility. The specific issue of pensions highlights the relation between Korea’s Confucian tradition and modern life. Millions of pensions are controlled by companies like LG, Lotte, Hanwha and Hyundai. A life-long corporate career, with a secure pension at the end, is, surprisingly perhaps, the dream of many graduates. Why? Because of the alternative: a retirement that depends on family support or private savings. Even the Korean family, a bastion of Confucian culture, is now seemingly less attractive than this corporatist career. As in North Korea the choice between security and poverty is stark. An in-built delay of ten years before pensions are paid in full cripples many: poverty, anxiety, homelessness, and anxiety induced sickness, are endemic. One 2018 Korea Economic Research Institute report reckoned 43.4% of South Korea’s elderly were impoverished; that is, three times the OECD average of 14.8%. A Korea Herald article in February 2021 described elderly folk finding and selling old cardboard to survive. Add to all this declining birth rates across Asia, including Korea – and with them families able and willing to care for aged parents – and the attraction of this new corporate culture is clear. But, as we have seen, these parent-like companies also serve to stratify society and reduce social mobility by freezing the job market and frustrating professional ambition. Regionalism is also a factor in all this, with parties and companies favoring particular provinces. Collectively we are witnessing the dichotomy seen in the Joseon era between the high status and security of ruling class Yangban officials with their proud, undiversified know-how, and the state and status of the lower orders who were, and are, susceptible to the vicissitudes of politics, climate, harvest, crops, officialdom and family strife. As they say, plus ça change.

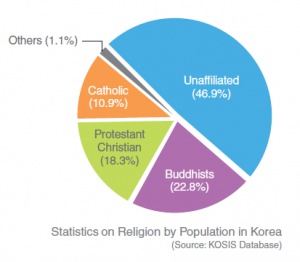

The impact of Korean Confucian culture on the perception of women is also illuminating. Of course, Korea is not unique, but Confucian influence on national laws adds a significant new dimension. Laws that enshrined male headship of the home were finally abolished in 2008. As Hyunah Yang has shown, terminology and legal provisions relating to this male model of domestic leadership are directly traceable to the Joseon era (‘Colonialism and Patriarchy’, in ed. Yang H., Law and Society in Korea [Elgar, 2013], 45-63). The effect has been that until recently formal and informal barriers limited the participation of women in Korean society. The old principle Nae/Wae (Lit. Inner/Outer) – that is, that a man’s role is ‘outside’ to deal with politics, education and business, and a woman’s is ‘inside’ to attend to all matters of hearth and home – still guides older Koreans. Changing attitudes towards the sexes (and to sexuality) in younger South Koreans are the result of education, globalization and a willing embrace of web values and social media (see fig. 1 on Korean religiosity).

Covid-19 and renewed tension between North and South Korea have also brought to the fore the legacy of Confucian culture. The pandemic has wreaked havoc on traditional family gatherings and annual ancestral rituals, which the Joseon era privileged. As the Korea Times reported (19 September 2020), offerings to deities – apart from the goddess of smallpox – were banned at the height of the pandemic. The normally close ties of family and work that Koreans enjoy have been profoundly disrupted. Even the Hoesik (the small-scale social gatherings after work of employers and employed) have been restricted. The elderly, who were already suffering financial hardship, have been exposed to coronavirus without the wherewithal to fight it physically or (because medicines are costly) financially. Though not directly attributable to Confucian practice, negative perception of South Korean action during the pandemic – with its imposition of among the harshest lockdowns worldwide – has stirred anti-Asian feelings in the West and renewed awareness of cultural distinctives. The counter argument carries weight: Korean compliance with lockdown, mask-wearing and social distancing, almost certainly suppressed transmission. Whether this readiness to comply was produced by Korean Confucian hierarchism or a fear of reprisals is unclear.

With regard to North-South relations. The smoldering conflict between the two Korean states has produced a new social stratum in the South, namely, escapees from the North. Most have come via China, some through third countries, a handful across the dangerous Demilitarized Zone. Evidence suggests North Koreans have struggled to adapt to life in the Republic. Their skills, expectations and credentials do not translate well cross the border. Adjustment programmes do little to help integration. Many North Koreans live on the edge of South Korean society, their employment opportunities and money limited, their suicide rates high. Younger South Koreans, with no memory of the conflict and few active family ties in the North, appear particularly disinterested in helping their Korean cousins. Self-interest, higher educational standards, and very different cultural values, make them less ready or willing than their elderly neighbours – for many of whom the sub-division of the peninsula remains a pan-Korean national tragedy – to show hospitality to the new arrivals.

One final point about the relationship between classical Korean Confucian culture and the present day. Despite the widely reported success South Korea’s Protestant mega-churches, study of the cultural roots of Korea (North and South) and their impact on current realities in the Peninsula, reveals a pervasiveand persistent rationalism in Korean popular culture. After the Goryeo era (918-1392 AD), when Buddhist faith and practice were preeminent, the Joseon dynasty saw no one religion acquire a comparable state-sanctioned primacy. Many faith traditions thrived (including various traditions of Catholicism, Buddhism and shamanism), but society at large was imbued by a-religious/irreligious Neo-Confucianism, or secularised, socialistic pragmatism. As emphasized at the outset, both of these thought traditions nurtured social differentials (economic and relational) and,as illustrated, a wide range of practical connotations (i.e., pensions, male headship and the disempowerment of women). That said, a precise correlation of Korean Confucianism on Korean life north and south of the border remains disputed. However, I would argue, if the legacy of Confucian tradition is not carefully integrated into contemporary geopolitical analysis of North and South Korea, outsiders will never penetrate the cultural mist and complexity of these two, very different regimes. Attitudes to language, family, faith, finance, society and state power are ultimately exegeted here not by projected Western values but inhabiting Korean ones. And, I should add, if peace or unity are ever to come to the Korean peninsula it is not going to be by external intervention but internal recovery of, and respect for, the traditions that formed this one, ancient people.

Dr Tomasz Sleziak, Research Associate (Postdoctoral Fellow, Ruhr-University Bochum)