- China in Pakistan: Will CPEC build or destroy a nation?by Iram Naseer Ahmad

Sir Angus Deaton FBA (b. 1945) (Bengt Nyman, Wikipedia) The Nobel Prize-winning British American economist Sir Angus Deaton’s (b. 1945) The Great Escape: Health, Wealth and the Origins of Inequality (Princeton, 2013) is a trenchant critique of a world where inequality prevails and advances in medicine are not matched by equality in care or provision. To Deaton, health and wealth are almost always connected; so healthy populations are more productive and financially robust, while wealthy communities invest more in healthcare, infrastructure development, education and research. And, he maintains, what is true nationally and internationally is true regionally; so, a region’s health is linked to its economy, likewise its education, employment, standard of living and vision for its future. Despite claims to the contrary, government policies invariably reinforce regional variants and stereotypes, he claims. But he also challenges the rationale for, and delivery of, international aid. Unless consciously resisted, international aid becomes, he contends, an instrument of control and an agent of economic and political dependency. In their place, Deaton wants policies that encourage integrity, independence, and self-sufficiency rather than corruption, debt and stifling bureaucracy.[1] Deaton is a useful foil for this Briefing on the economy and development of Pakistan in the first quarter of the 21st century; in particular, on the impact nationally, regionally, and culturally of Pakistan’s increasing economic dependency on China.

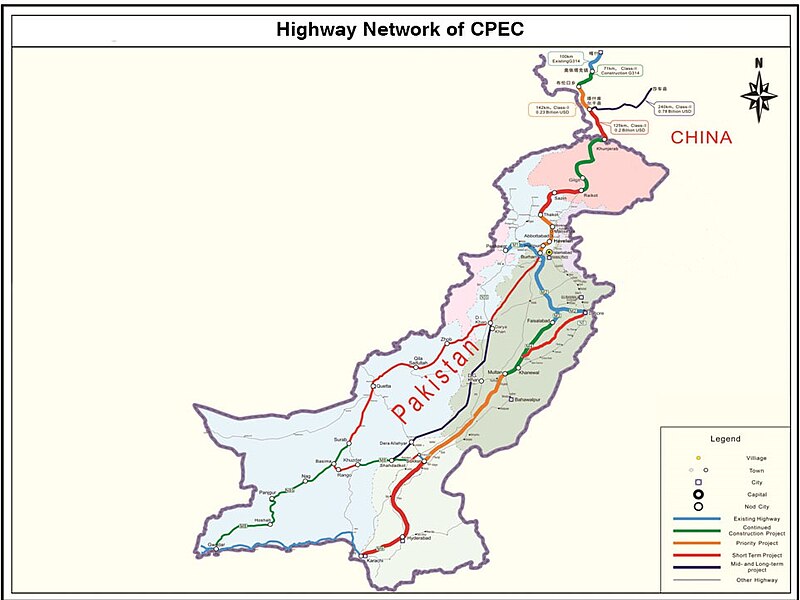

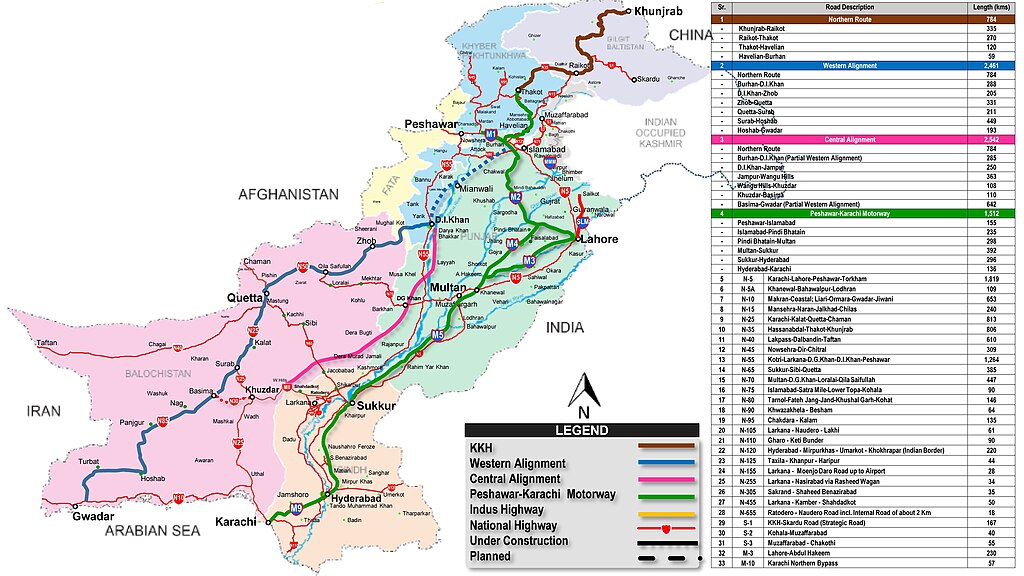

CPEC Roadway map (Wikipedia) From its formation in 1947, Pakistan has struggled to develop a strong central government and effective federal system. At the macro level this has stifled Pakistan’s economy growth and fostered political instability: at a micro level provinces such as Baluchistan, in the SW of the country, have struggled to develop socially and economically and been the seed-bed of civil unrest and military insurgency.[2] Weak internally and threatened regionally by India to the South and radical Islamism to the North and West, Pakistan, with its strategic position and accessible coastline, has long offered imperialist powers an attractive prize. Of these, Communist China is the most recent … and probably most powerful. The $62bn, 3000km China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which was launched on 20 April 2015,[3] is at the heart of PRC’s ‘Belt and Road Initiative’. It offers China a route to the Indian Ocean (at Gwadar Port) and Pakistan a path to economic stability and political security.[4] But the project has been fraught with difficulties from the outset, not least for its inequitable economic, and toxic ecological, impacts and recent violence against some of the 1200, or so, Chinese working on the project in Pakistan.[5] Mindful of Deaton’s argument, we look here at the degree to which CPEC promotes equality or inequality in Pakistan today, and particularly the degree to which Baluchistan is a useful case study for Deaton’s thesis.

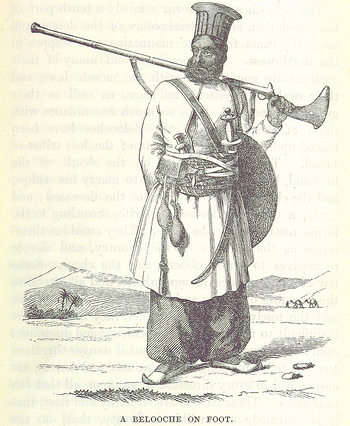

(Wikipedia) To focus on the Baloch people and Baluchistan for a moment. Baluchistan is a plateau region of some 350,000 Km2 (including parts of Iran and Afghanistan) with 18-19m. inhabitants. The route of CPEC across Baluchistan in Pakistan has been much debated and, in the process, opened old wounds. As a self-consciously distinct ethnic region, Baluchistan has a long and fractious history. Long before Pakistan was imagined, regional governments and local issues spawned strife locally and suspicion nationally (and internationally). When a western route for CPEC was proposed (through Baluchistan), the history of the region and failed attempts to impose law and order and complete other regional projects, were cast into the limelight. Local Baloch were as suspicious as others in Pakistan. But CPEC offers whichever regions it crosses immense economic benefits and political kudos.[6] This was recognized in Baluchistan when officials debated the pros and cons of the project and contested the route.

Balochs in traditional dress (Elyas 1588, Wikimedia) As a useful case study, CPEC and Baluchistan prompt questions about how the opinions of locals are discerned and determined, how previous projects impact current thinking, how doubts and fears are named and addressed, and how central government – let alone Beijing – can reassure locals that the economic and political benefits of CPEC (or other large-scale projects) outweigh its cultural and ecological costs. Spread-sheets and canvassing – to say nothing of bribery and coercion – are questionable strategies if cultural defensiveness and tribal loyalties are the real issues driving attitudes and decisions. But how should or could the Pakistani government in Islamabad process this ‘affective’ data? And, as importantly, to what extent will the economic factors and power differentials Deaton identifies impact their thought and action? After all, if CPEC increases inequality in Pakistan to what extent can it be legitimately said to benefit Pakistan nationally?

To open up these issues, I focus on three key issues that case studying Baluchistan suggests.

i. Culture, power and coercion

A traditional Baloch dance (Ahsan Farooq Bakhri, Wikimedia) A clear sub-text in Deaton’s The Great Escape is that economic and political factors directly affect, and are affected by, local dynamics. In this, ‘culture’ in its broadest sense has a key role to play. That is, everything that shapes the way a person or community perceives and receives reality is an expression of their ‘culture’ and is, we might say ‘culturally conditioned’. ‘Culture’ infiltrates and catalyzes every aspect of life globally. It shapes perception of success and failure, identity and morality, joy and pain, unity and community.[7] Globalization has enriched cultural awareness through its creation of new mechanisms for cultural exposure and cross-cultural learning. It has also acted as a counterpoint to ancient cultural norms and local loyalties. 21st-century life is essentially interactive as individuals learn from others and adopt new practices and customs. Few places are immune to the impact of the tsunami of globalized ‘culture’ today. Certainly not where political, economic, and cultural interaction is promoted, as in Sino-Pakistani cooperation over CPEC.

Chagai district in Baluchistan (Milenioscuro, Wikipedia) To some observers, CPEC offers China and Pakistan an excellent opportunity to develop deep cultural, political and economic ties, with greater exposure to each other’s history, values and identity offering opportunities for mutual enrichment, regional stability and ultimately greater global harmony. Cynics see things rather differently! However, as Deaton recognizes, international agreements can bring regional benefits. CPEC doesn’t only offer, then, a means for Sino-Pakistani cooperation, it provides Baluchistan with a path to self-promotion and a greater national and international profile. Alongside economic and strategic benefits, CPEC can showcase Baluchistan’s rich culture and help develop cultural understanding regionally, nationally and internationally.[8] As one resident of Chaghai[9] is quoted as saying, CPEC is ‘far more than a local project’: it is an international project with global significance. Through it, many will have a chance to discover the rich culture and traditions of Baluchistan – not least, other Pakistanis.[10] So an international project becomes a mechanism for national integration.

Saindak Lake, Chagai district (laibaimran003, Wikimedia) But return to those cynics for a moment. Deaton’s The Great Escape fuels the fires of those who are habitually (and often justifiably) suspicious of international agreements between the world’s superpowers and other nations. What criticisms can, and should, be legitimately laid at the feet of those who conceived and now operationalize CPEC? What, for example, is the real impact of this multi-billion-dollar project on the political, economic, military and cultural relations between China and Pakistan. Does it really benefit the population of either country, let alone the Balochs? The simple fact is suspicion of China runs deep in Pakistan. Far from allaying fears of cultural and economic colonialism, a growth of Confucius Institutes across Pakistan has (as elsewhere globally) prompted accusations of covert infiltration and ideological subversion.[11] Deaton’s critique of international aid is, perhaps, applicable to this quite different method of inspiring cultural dependency. We will return to this later when we look at lessons to be drawn from the cultural analysis of experts Thomas Piketty[12] and Francis Fukuyama.[13] For now, we should acknowledge that all of Pakistan’s international relations are compromised to a greater or lesser extent by its long history of political instability, ethnic violence, economic volatility and coercive military. China may seek to mitigate the impact of this on-going insecurity on its border, but CPEC does not solve all of Pakistan’s problems.[14]

ii. Money, maps and motivation

(Gerhard Streminger, Wikimedia) Scottish economist Adam Smith’s (1723-1790) The Wealth of Nations (1776) drew attention to the close correlation between wealth and power, between those who control the purse strings and those who shape the lives of others. Capital controls the market and the nation. The seeds of the inequality Deaton addresses are sown by financial differentials. The few with more not only control the lives of those with less: they also shape the conditions in which those lives are lived. The self-interest and selflessness of the few create feasting or famine for the many. Open competition threatens vested interest as much as a ‘closed shop’ the price of goods. John Perkins’s Confessions of an Economic Hit Man (Berrett-Koehler, 2023) puts a modern-day twist on Adam Smith. Now a clandestine community of ‘economic hit men’ (EHMs) exploit governments and national budgets to enrich multinationals and an elite super-rich few. While most face financial stringency or poverty, wealth is controlled by, and in the hands of, a few. How is all this relevant to CPEC and Baluchistan? Both Smith and Perkins prompt us to ask, who really benefits from a major state project like CPEC? Or, put another way, how widely distributed are the socio-economic benefits of CPEC?

Debate about the benefits of CPEC have, as indicated earlier, focused from the outset on the route the new economic corridor follows. Since the signing of the agreement in April 2015, people in Baluchistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) have sought to keep to the originally proposed (western) route; that is, one which crosses their poor, underdeveloped, region/s. With little consultation, and to the dismay of many in Baluchistan and KPK, the ruling, centre -right Pakistan Muslim League (PML) have agreed a new (eastern) route that passes through the heartland of PML’s political power, Punjab. Far from enhancing national integration CPEC has become a symbol for many, especially in Baluchistan and KPK, of a corrupt political elite with a strong regional bias.[15] Instead of improving the lot of the already marginalized poorer communities in Baluchistan and KPK, CPEC will merely increase inequality and add weight to the argument and analysis of Smith and Perkins about wealth and power. Already privileged Punjab will become more wealthy and powerful at the expense of other Pakistani citizens. Cries of injustice are loud and clear. Regional unrest is rife. As one resident of Dera Murad Jamali, in Nasirabad District, Baluchistan, points out, far from nurturing national life CPEC threatens to fragment Pakistan.[16] Few analysts doubt China’s denial of complicity – indeed, cynical pleasure – in creating this internal crisis. If we heed Piketty and Fukuyama’s counsel, social harmony is built on the inseparability of income and identity, wealth and self-worth.

(Ytpks896, Wikimedia) Three further elements of this crisis deserve note. Picking up earlier themes, they each serve in different ways to validate Deaton’s thesis.

(Orlich, Leopold von, Wikimedia) First, from both inside and outside Baluchistan the province’s reputation for lawlessness and civil unrest has been used to explain the PML’s change of mind about CPEC’s route. With the eyes of the nation and world on CPEC, how would Pakistan look if the project succumbed to regional instability? To advocates of the project and critics of the government, the answer is clear: invest in policing and counter measures to safeguard society. As one Ziarat resident claims,[17] ‘Long before CPEC, the government’s duty has been, and is, to uphold law and order.’ Like it or not, the success or failure of CPEC will reflect on the government’s ability to govern. After all, some would argue, if a government can’t keep the peace, to whom do its citizens look for safety? This issue is in the mind of many in Baluchistan.

Second, the impact of CPEC on Baluchistan illustrates another common consequence of financial redistribution: those who have wealth position themselves to gain more, those without remain paralyzed by their poverty. Critical commentary on the CPEC in Baluchistan is quick to point out, for example, that the limited resources of residents near Gwadar Port mean they lack the wherewithal to invest in the project on their doorstep,[18] while affluent incomers and investors milk it greedily. Inequality and opportunity are, as Deaton argues, directly connected here to wealth, with society and social harmony fractured by this. Locals are displaced, outbid and outmaneuvered by incomers with deeper pockets. Paradoxically, it may seem, a new sense of disenfranchisement and deprivation often follows inward investment.

(Bjoertvedt, Wikimedia) Third, as intimated earlier, frustrated hopes awaken bitter memories. The potential benefit of CPEC to Pakistan as a whole, and to some in Baluchistan, has made the project for many a harbinger of national renewal. Peace and prosperity after years of conflict, drift and decay.[19] Indeed, even residents of Gwadar associate CPEC with development, peace, and happiness; or, as one man in Chaghai is quoted as saying, ‘CPEC represents a remarkable leap towards progress and development.’ Despite the optimism of some, many Balochs struggle to believe good will come of CPEC. Stirred emotions have awakened old memories and deep insecurities. As noted earlier, failed (or prejudicial) projects – notably, the Reko Diq and Saindak Copper Gold project – have made locals cynical and pessimistic. As another resident of Chaghai says: ‘I am from Chaghai, where you can find Reko Diq and Saindak Copper Gold Project. Despite living in Chaghai, we have seen none of the benefits from these projects.’ Adding, ‘Why should we expect CPEC to benefit the people of Baluchistan?’[20] As this illustrates, a country or region’s ‘success’ is about more than material benefits: it is about the soul and spirit of the people and place. Crushed spirits cannot sing and dance.

The $7 bn Reko Diq mine, in which Saudi Arabia has taken a minority investment ($1.7 bn in April 2024) (Asia Times) iii. Environmental Impacts

In keeping with a majority of people worldwide, Pakistani’s are sensitive to ecological issues and the impact of global warming on climate and rainfall. This beautiful planet, where life is uniquely formed and sustained, is, for many, threatened as never before by industrial waste and demography. Without swift action, the world risks creating an uninhabitable wasteland. As ecologists point out, ‘We have no viable Plan(et) B’.[21] CPEC has raised the profile of the environmental threat facing Pakistan in new and vivid ways; indeed, critics of the project are clear, it’s impact on the country’s biodiversity, air and water quality, and desertification now and in coming decades, far outweighs its potential benefits.[22] Take, for example, the Thar-I and Thar-II coal power plants in Sindh province, which are planned to produce 75% of CPEC’s energy output. Large parts of Sindh and Punjab are already reporting heavy seasonal smog with an associated rise in respiratory problems, road accidents and hospital admissions. As Deaton asks us to consider, if wealth and health are linked, where is the greatest benefit of CPEC being felt? We might also point to the extensive deforestation linked to CPEC, with large tracts of ancient woodland cleared for new road and rail links and likewise ask, will all this infrastructure development really benefit those whose land is lost or violated in the process?[23] In Mansehra, Torghar, Kohistan and Battagram districts alone an estimated 54,000 trees of every kind (viz. fruit, forest, hard and soft wood) have been felled. If trees improve air quality and help protect against erosion from rain and flash floods, has this been sufficiently factored into assessment of CPEC’s long-term impacts? Isn’t Pakistan’s already vulnerable terrain yet further weakened by such poor long-term ecological planning? critics of the project ask.

The shrinking forests of Baluchistan (Balochistan Point) CPEC is already having a significant impact on biodiversity in some areas of Pakistan; perhaps especially in its northern, entry-point region where the strategic and socioeconomic benefits are supposedly clearest. Here locals point to CPEC’s dramatic negative impact on their finely balanced ecosystem/s and ancient, pastoral, way of life.[24] Established principles of ecological responsibility that China and other developed nations uphold in international fora become, it seems, inconvenient when money and power are at stake. Critics of CPEC identify the need to balance carefully new technologies, what people need and care for the planet. To-date, CPEC is more often associated with habitat loss, the dislocation and fragmentation of villages, the endangering of micro-cultures and communities, deforestation and pollution. Like nomadic tribes, species of animals – especially, the rhesus macaque, Himalayan brown bear, Kashmir gray langur, Indian wolf, Indian leopard, snow leopard, markhor, Kashmir red deer, white-bellied musk deer and Siberian ibex – are threatened with reduced numbers or extinction.

(Asian Environmental Youth Network) Pakistan’s environmental will and regulatory system are all under the microscope in CPEC.[25] Time will tell whether either is fit for purpose. The front-line ecological threat Baluchistan faces further illustrates the inequitable government policies Deaton indicts, with an already weak community footing the bill for an elite minority.[26] If ‘impact assessment’ ran to culture, climate and quality of life, the limited – and limiting – role of money might be more clearly seen. To be sure, Pakistan’s environmental agenda would be comprehensively overhauled!

Policy Recommendations

Mindful of the preceding, I end with bullet point policy recommendations. My aim here is to ensure CPEC both delivers what it promises and sets a standard of good practice for others.

- The route dispute must be resolved (either through All Parties Conferences or another means). As in every aspect of CPEC, open access to data and transparency are key.

- Government priorities for CPEC must be openly discussed and equitably decided. Elitism breeds separatism.

- Law and Order must be clearly and justly articulated and implemented in every part of Pakistan, including Baluchistan. Separatism and nationalism cannot peacefully coexist.

- Peace and justice in Baluchistan depend on central government engaging effectively with the established tribal system of authority, ‘Sardai Nizam’. Historically, an instrument of social cohesion and stability, Sardai Nizam can be as oppressive, elitist, and self-interested as the government. Skillful diplomacy and integrity are required.

- Much criminal and insurgent activity in Pakistan has a connection with Afghanistan. For CPEC to succeed and Baluchistan benefit a secure border with Afghanistan is a prerequisite.

- Controls and quotas should be implemented to ensure locals in areas such as Gwadar can have a practical and financial stake in the building and maintenance of CPEC.

- The rights, lifestyle and livelihoods of indigenous ethnic minorities like the Balochs must be protected. Lack of data on, and ethnographic study of, the relation between indigenous people and local biodiversity, and on the cultural and socioeconomic impact of CPEC on minorities, leaves them exposed to threat and abuse. Research can help shape protective countermeasures.

(Strategic Vision Institute) Conclusion

Despite deep concerns among the Balochs, CPEC is still generally perceived to be a good thing. It is widely viewed as a hope-filled symbol of peace, prosperity, integration and renewal. If areas of concern are addressed and a redistribution of power and wealth built into the DNA of CPEC, it can provide a model for other transnational projects. In terms of the ecological issues it raises, it affords a unique opportunity for government agencies and Pakistani children to learn wise stewardship of the world’s resources and new lessons on care for endangered tribes and creatures. Failure risks destroying a fine country, beautiful countryside and, worse, a nation and people’s dreams.

Dr Iram Naseer Ahmad, Research Associate

As in all Oxford House Briefings, every effort is made to attribute images where information is available.

[1] Deaton, A., The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality (Princeton, 2013).

[2] Samad. Y., ‘Understanding the Insurgency in Balochistan’, Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 52.2 (2014): 293-320.

[3] Beijing has recently proposed to Islamabad an ‘upgraded version’ of CPEC; see Zhang Tong, ‘China calls for ‘upgraded’ CPEC, calls on Pakistan to ensure workers’ safety’, South China Morning Post, 15 May 2024: https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3262819/china-calls-upgraded-cpec-calls-pakistan-ensure-workers-safety; accessed 13 September 2024.

[4] Pakistani officials claim CPEC create more than 2.3m. jobs (between 2015 and 2030) and add 2-2.5% to the nation’s per annum economic growth.

[5] On violence this year against Chinese workers, particularly by Baloch separatists, see A. Siddiqua, ‘Security for Chinese workers in Pakistan will always be elusive’, NikkeiAsia, 23 April 2024: https://asia.nikkei.com/Opinion/Security-for-Chinese-workers-in-Pakistan-will-always-be-elusive; accessed 13 September 2024; A. Hussain, ‘Sharif’s Beijing trip: Can China-Pakistan Economic Corridor be Revived?’, Al Jazeera, 3 June 2024: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/6/3/sharifs-beijing-trip-can-china-pakistan-economic-corridor-be-revived; accessed 13 September 2024; S. Fazl-e-Haider, ‘Pakistan: The dangerous reality of working on China’s megaprojects’, Lowy Institute, 5 April 2024: https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/pakistan-dangerous-reality-working-china-s-megaprojects; accessed 13 September 2024.

[6] Akins, H., ‘China in Balochistan: CPEC and the Shifting Security Landscape of Pakistan’, Baker Center for Public Policy, Tennessee (2017).

[7] Carens, J. H., Culture, Citizenship, and Community: A Contextual Exploration of Justice as Evenhandedness (OUP, 2000).

[8] Shaffer, R., China-Pakistan Relations: A Historical Analysis (OUP, 2018).

[9] Chagai in NW Baluchistan is both a city and the largest district area in Pakistan.

[10] Zia-ur-Rehman, M., H. Sabri, W. Ishaque, ‘CPEC: Strengthening the economy through microfinance’ (2018): https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325537858_CPEC-STRENGTHENING_THE_ECONOMY_THROUGH_MICRO-FINANCE; accessed 7 September 2024..

[11] Ali, Z., W. A. Khan, T. Khan, ‘Economic and Socio-cultural Impacts of China-Pakistan Economic Corridor under One Belt One Road’, Pakistan Journal of International Affairs 5.2 (2022): 1758-1774.

[12] Piketty. T. and A. Goldhammer, Capital in the Twenty-First Century (Harvard, 2017): https://books.google.com.pk/books?id=dqEuDwAAQBAJ; accessed 7 September 2024.

[13] Fukuyama, F., Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2018).

[14] Small, A., The China-Pakistan Axis: Asia’s New Geopolitics (OUP, 2015).

[15] Han, E. S., A. Goleman, et al., ‘China Pakistan Economic Corridor: The Route Controversy’, Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 53.9 (2019): 1689-99.

[16] Cf. Butt, K. M. and A. A. Butt, ‘The impact of CPEC on regional and extra-regional actors’, The Journal of Political Science 33 (2015): 23.

[17] Ziarat is a city and district in Baluchistan.

[18] Sial, S., ‘CPEC in Balochistan: Local Concerns and Implications’, Pakistan Institute of Peace Studies (Islamabad, 2018).

[19] Ullah, S., et al., ‘Problems and Benefits of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) for Local People in Pakistan: A Critical Review’, Asian Perspective 45.4 (2021): 861-876.

[20] Barrech, D., et al., ‘Balochistan’s Potential under CPEC: Opportunities and Challenges’, Qualitative Research 23.2 (2023): 235-257. The Reko Diq mine has a mining life of 40 (est.) years. It contains an estimated 5.9 billion tonnes of ore grading 0.41% copper and 41.5 m. ounces of gold.

[21] Jenkins, S., et al., ‘Is Anthropogenic Global Warming Accelerating?’, Journal of Climate 35.24 (2022): 7873–7890.

[22] Razzaq, N., ‘China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) and Climate Change in Balochistan: Problems and Prospects’, Journal of Development and Social Sciences 4.4 (2023): 433-8.

[23] Khan. S., et al., ‘Climate and Weather Condition of Balochistan Province, Pakistan’, International Journal of Economic and Environmental Geology 12.2 (2021): 65-71.

[24] Khan, A., et al., ‘The Impact of CPEC on Pakistan’s Economy: An Analysis Framework’, Russian Law Journal 11.125 (2023): 252-66.

[25] Shapiee, R., R. Idrees, .Luo H., ‘How Logistics Investment Arrangement Is a Key Concern to China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC)?’ International Journal of Asian Social Science 8.11 (2018): 1059-1067.

[26] Akhtar A. S., ‘Balochistan versus Pakistan’, Economic and Political Weekly 42.45/6 (2007): 73-79.