If you can remember going on a London tube (!), you will recall the disembodied voice that warns, ‘Mind the Gap’ (between the train and the platform). It is a physical counterpart to the old proverb, ‘There’s many a slip ‘twixt cup and lip’. The gap between aspiration and achievement, theory and practice, claims and reality, should worry us all. That’s my theme.

In Britain (as in many other places), the practical and intellectual gap between the political horizon and the need for change – radical social and political change – is very deep and very wide. It is a gap that ought to inspire conscience-stricken fear and ground-shaking remorse. Too often, dubbing a thing ‘radical’ is an easy way for opponents to eviscerate criticism and shut down debate as ‘alarmist’ or ‘extremist’. Not here, I hope.

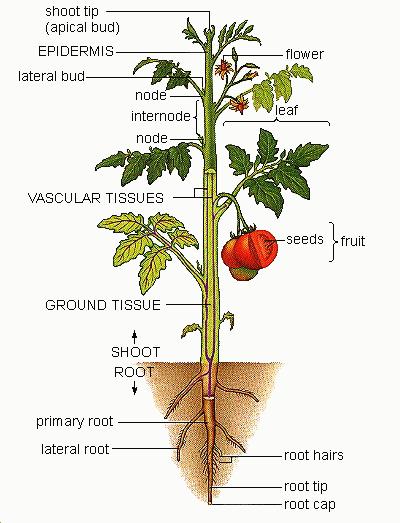

Being ‘radical’ is linguistically about getting to the root, or heart, of things. Applied to problems, it connotes a readiness to ‘think outside the box’, to ‘seize the day’ and confront problems and solutions; not twisting, turning, or tweaking issues so matters get worse or results become blurred. To be radical is to avoid evasive delay in lengthy ‘reviews’ and cynical denial in paper-thin institutional ‘cover ups’, so that presenting problems are allowed to evaporate in the noon day sun of a media firestorm or shrivel on the over-crowded vine of parliamentary business.

Compared to secular figures, religious leaders have the advantage of an acknowledged starting point, a perspective from which they think and speak. With this, too, an accepted way of naming the risks of ‘business as usual’ and voicing, potentially at least, ‘radical’ responses. The religious code for this activity and perspective is ‘prophetic’, with ‘prophetic’ signifying as much insight as foresight, a divine mandate to scrutinise and criticise the present as to see the future or propose solutions. If you like, it is a privileged right to name wrong and to cite ethical principles to guide change and, in navigational terms, make a ‘course correction’.

In 2020, Pope Francis (b. 1936; r. 2013-present) published Let Us Dream: The Path to a Better Future (Simon & Schuster). It is a remarkable little book; as Julian Coman says in a review in The Guardian (29 November 2020), ‘There is a spiritual urgency and warmth to Let Us Dream that will appeal to lay readers as well as the faithful.’ In the midst of COVID-19, the book’s theme is to ‘dream big’, denounce ‘the lie of self-sufficiency’, embrace ‘fraternity’ as ‘the new frontier’ and above all to see that ‘… without the “we” of a people, of a family, of institutions, of a society that transcends the “I” of individual interests’, we are left with ‘a battle for supremacy between factions and interests’. In many respects, Let Us Dream is a user-friendly synopsis of Pope Francis’s third encyclical, which appeared the same year, with its evocative Franciscan title Fratelli Tutti (Lit. all are brothers). In both texts, the Pope is in prophetic mode. But Let Us Dream has proved to be so much more. The global pandemic provided a context in which ‘prophetic’ words and ideas from a religious leader, speaking sensitively at a time of unprecedented uncertainty and upheaval, could be heard. The Guardian wasn’t unique: the secular Press carried many positive reviews of the Pope’s book. Waves of appreciation washed through Catholic circles. There was none of the usual, ‘The Church shouldn’t meddle in politics’ – although, the book does describe what politics should be about … but sadly, too often isn’t.

The subtitle of Let us Dream is significant, The Path to a Better Future. It is not an accurate description of the book’s content. Popes do not, after all, tend to prescribe in detail how to get from A to B. They provide counsel on where to find, and how to read, signposts for faith and life. The religious code for this is now ‘reading the signs of the times’, or simply ‘discernment’. But choosing paths, building roads, turning principles into practice and plans into realities, these are tasks for politicians and civil servants, policy-oriented academics, and experts in other disciplines. And, I would argue, all should be pursued in dialogue, and in the closest possible collaboration, with ‘civil society’ actors and agencies.

A striking feature of Pope Francis’s brand of prophetic writing is how it dovetails with those who begin where he, as a religious leader, appropriately ends. Take for example, the collaborative volume, by the eminent American political scientist Robert Putnam (b. 1941) and gifted young social entrepreneur Shaylyn Romney Garrett, The Upswing: How We Came Together a Century Ago and How We Can Do it again (Simon & Schuster, 2020) or the more recent, very thoughtful, work by the British Labour MP Jon Cruddas (b. 1962), The Dignity of Labour (Wiley, 2021). Putnam and Garrett’s book tracks the shift the authors see in the US from the passionate individualism of the 19th century and emergent communitarianism of the first two-thirds of the 20th century to what they bemoan as the regression of America into its aggressive, competitive, individualist culture. Cruddas’s short, sophisticated book is about work. It is a plea for socialist thought to resist the ‘siren call of technological determinism’ and (especially in the context of COVID-19) to (re-) embrace ‘an ethical socialist politics based on the dignity and agency of the labour interest’. Both books go into detail about what it will take to make real, radical, life-giving change. Tellingly, the secular weekly New Statesman invited the former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams (b. 1952) to review both books: his voice, like Pope Francis’s, has weight.

The gap between the reality of politics in the UK and the kind of radical change envisioned by Pope Francis can seem unbridgeable. Let us Dream points to a way to span the divide. It promotes change ‘from the margins’, popular movements that the Pope celebrates as ‘social poets’, in their ‘mobilising for change’ and ‘search for dignity’. He explains: ‘I see a source of moral energy, a reserve of civic passion, capable of revitalizing our democracy and reorienting the economy.’ He is not talking about a trendy new form of populism, which ‘denies the proper participation of those who belong to the people’ and allows ‘a particular group to appoint itself the true interpreter of popular feeling’. No, as an Argentinian shaped by the memory, pain and triumphs of Latin America, his vision and hope lie in a transformative social energy sourced ‘from the margins’ and worked out in dusty public squares and the corridors of secular power.

The ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement has given us a glimpse this kind of change is possible. Building a strong, sustainable coalition for radical change in Britain is a daunting prospect. Even progressive politics traditionally prefers incremental adjustment, not radical ‘course correction’ that exposes the body politic to the risk of capsizing. Finding a common theme to unite and mobilise minds might be a place to start. Perhaps a ‘Campaign to Defend Democracy’, as in South Africa, or an explicit prioritising of the marginalised. In the UK, this would need a strong, new, socio-political consensus that united the hitherto disparate energy of lawyers, Human Rights campaigners, environmental lobbyists and a host of civil society actors. Tall order, perhaps.

To my mind, Britain faces a number of acute challenges as it responds to the present. First, in relation the pandemic. Though a longing to ‘return to normality’ is a perfectly natural and inevitable reaction to the ‘abnormality’ of the pandemic, we cannot and should not allow ourselves to return to the injustice, anger, and divisions of the ‘old normal’. But how do we avoid that? Second, we have problems with our history. Many still want to hold on to the myth of a brave and glorious past: in part, perhaps, to compensate for recent decline. But, as Pope Francis states in Let Us Dream, ‘History is what was, not what we want it to have been, and when we throw an ideological blanket over it, we make it so much harder to see what in our present needs to change in order to move to a better future.’ So how do we unpick ourselves from history? Big problems both.

Post-Brexit Britain is vulnerable, as it battles the global pandemic and seeks to build a sound economy and sustainable society. With its large parliamentary majority, those who have most control over the past, present and future – namely, the Johnson government – present the paradox of a very British form of authoritarianism that seems hell-bent on undermining the hard-won structure of governance itself. I am speaking, of course, of what some see as the Johnson government’s preference for more control by the few and less accountability, more benefit for the few and less for the rest, more greed, sleaze, and self-interest as the order of the day. Government, that is, with a negligible concern for truth and thus equally negligible purchase on reality. Any vision of a better future refracted through what is good short-term for the Conservative Party. Gone are the days when political persuasion was preferred to strong arm coercion. Perceived dissent at the heart of the government is now, it seems, eradicated by censure, expulsion, denial and forced resignation.

Minds focussed by the grim prospect of devastating climate change are beginning to ‘think outside the box’, to consider ‘radical’ options unnamed and unnameable before. Across Europe we see a growing consensus around the need for economic transformation and the socio-political reforms that must accompany it. In Germany, the Green Party’s dynamic young leader Annalena Baerbock (b. 1980) might still be Angela Merkel’s (b. 1954; Chancellor 2005-present) successor. We can also discern a new consensus between religious and secular thinkers. Laudato Si, Pope Francis’s 2015 encyclical reinforces the UN’s 2009 Sustainable Development Commission report while rooting the ‘Green’ agenda in the Bible and doctrine of Revelation. The encyclical, like many others, calls for ‘swift and united action’ to address climate change. We haven’t seen such synergy in spiritual and secular thought since Roman Catholic emphasis on human dignity wed early Human Rights activism in the 1960s.

Two other events give hope that popular movements can bring change. First, the jury’s verdict in Minneapolis (20 April 2021) that one 46-year-old black life, George Floyd (d. 25 May 2020), matters enough to convict a local police officer of murder. The verdict wasn’t just because body cams and videos captured the incident: the four officers filmed beating Rodney King in 1992 were acquitted. Something had changed … because it had to. Second, the public outcry against the proposed Super-League for twelve European football clubs. Demonstrations by fans across Britain voiced values that matter to a football-loving public. Central to these was that, despite recent commercialisation, football is still an essentially local, competitive, community event. A few, greedy, multi-millionaire owners are not to sell this national treasure and squeeze the life blood out of smaller clubs, whose livelihood and passion lie in the rewards of skill, hard work, climbing leagues and winning competitions. Giant-killer Leicester City’s spectacular 2016-2017 season was rightly invoked to validate British football as a meritocracy with money there for smaller clubs who do well.

Perhaps you reject some of what was said against the proposed Super League, but what of the widespread appeal to community, to sharing of resources, to empowering the less well-off. Are these not sound morals for any society? If so, why don’t they appear more often in election manifestos? Why are they good for football and not for all of us, all of the time?

Pope Francis’s dream is about as ‘radical’ as it gets, both personally and socially. But he is not, like John the Baptist or a prophet of old, a voice ‘crying in the wilderness’ (Isaiah 40.3, John 1.23). He speaks of God from the world to the world. Martin Luther King’s (1929-1968) ‘dream’ of social transformation is a sober reminder, change takes time. Patience is prominent in Let Us Dream. Change can be slow and painful. Meanwhile, as that disembodied voice warns those waiting at a tube station, ‘Mind the Gap’!

Professor Ian Linden, Senior Associate