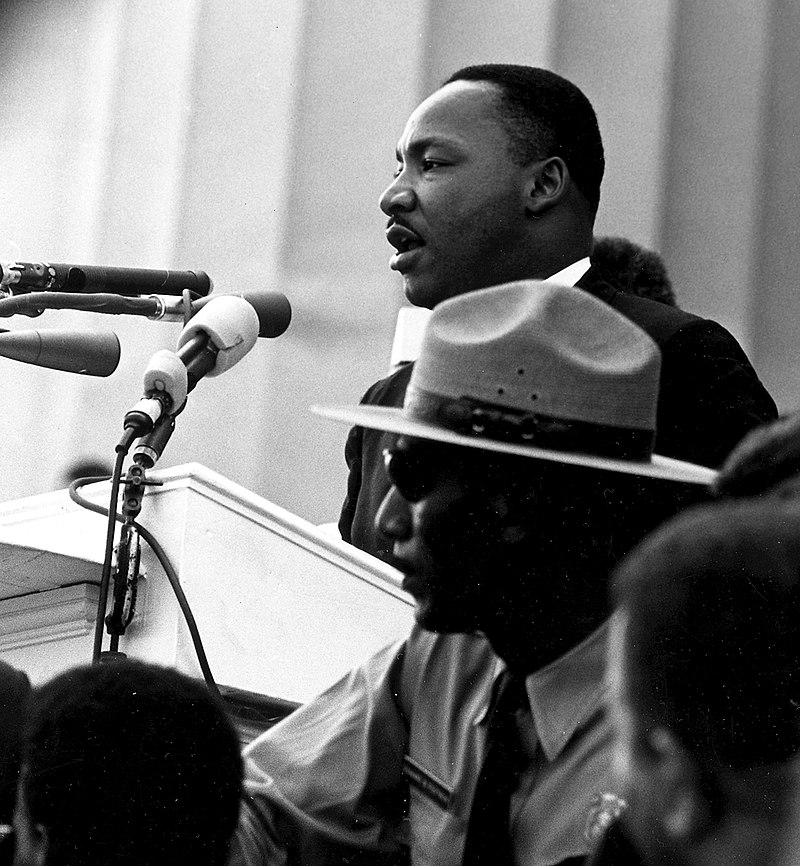

(Rowland Scherman, Wikipedia)

The American Civil Rights activist and martyr Dr Martin Luther King, Jr (1929-1968) wisely observed: ‘Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.’ As he continued, ‘We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.’ That is, like a garment without seam, humanity exists in an unbreakable, but fragile, network borne of our shared physicality and finitude, creativity and capacity for empathy, and, on a good day, universal sense of morality and ultimate responsibility. This shared identity creates a globalized set of duties and responsibilities. It also implies, ‘What harms one impacts all’. Seen in this light, the February 2021 coup in Myanmar was not just a national event, it was – and remains – a global tragedy, however much Myanmar is no longer a media highlight. The event and its aftermath deserve to be carefully studied, closely monitored and, where appropriate,severely criticized. For Burmese of every ethnicity, faith and cultural tradition are co-inheritors of a shared, humanitarian duty to care for one another and to be cared for.

(Claude Truong-Ngoc, Wikipedia)

The military coup on 1 February 2021 ended Myanmar’s brief experience of constitutional democracy. To set the event in context: the National League for Democracy (NLD) – led since 1988 by the long-term (and long-suffering) campaigner for constitutional reform, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi (b. 1945) – won 86% of the seats in the Upper and Lower Houses of the Assembly of the Union in the November 2015 General Election,[1] the first openly contested election to the Assembly since 1990.[2] The event was (and remains) of immense national, regional, and global significance. Though Daw Suu was barred from becoming President because of her registered foreign nationality, she was appointed to the newly created role of State Counsellor and effectively head of the government. In November 2020 – in an election overshadowed by the pandemic and persisting birth pangs of Myanmar’s nascent constitutional system – the NLD was re-elected with an increased majority in both houses.[3]

To many commentators, the future looked bright for Myanmar’s continuing national and economic renewal and broader integration into the international community. But vested interests, disrupted by Myanmar’s nascent democracy, were unhappy. The second largest party, the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), challenged the 2020 result claiming electoral fraud and errors in voter registrations. Dissent spread. On 1 February 2021, the day the new government was to be confirmed in office, the Tatmadaw, Myanmar’s multi-generational, mafia-style, military reclaimed power. Led once again by Senior General Min Aung Hlaing (b. 1956), the military State Administration Council (SAC) arrested 100s of parliamentarians (including Daw Suu and other senior NLD figures) and reimposed martial law. Myanmar’s brief, and fragile, experience of democracy came to an abrupt and violent end. The SAC’s infamous brutality returned. Popular frustration spilled out in urban violence. Protests were savagely suppressed. Reports of Human Rights abuse spread. Myanmar returned to its old, inverted normality under military rule, with arbitrary arrests and executions of critics, ethnic violence, widespread poverty and death, the norm. Since 2021, Western leaders appear to have forgotten Myanmar, embarrassed by Aung San Suu Kyi’s purported complicity in attacks on the Rohingya Muslim minority and disinclined to face off against China, Russia, and India over their devious support for the Tatmadaw’s hold on every aspect of Myanmar’s national, social, and economic life. Meanwhile, millions suffer the impact of the coup, feel the international isolation that changed perceptions of Daw Suu have created, and suffer as collateral damage from ASEAN’s ineffectiveness and from the politically more pressing and electorally impressive issues of the war in Ukraine, global warming, and balancing a nation’s books. Justice and injustice seemingly forgotten.

(Tatarstan.ru, Wikipedia)

My aim in this Briefing is not to rehearse oft-reported tales of ethnic and military violence, nor to join the chorus of voices calling on the international community to condemn the military junta and its brutal policies. Instead, my aim is to profile themes often ignored; in particular, six issues that render Myanmar more, and not less, deserving of international attention and humanitarian action.

i. The last Oxford House Briefing by Research Associate Krishna Saha (‘Rohingya Refugees: Resistance, Repatriation and Rising Violence’) explained the perilous predicament of the Rohingya Muslim minority. Cyclone Mocha has in recent weeks reminded the world of the fragility of human life and local infrastructure in SE Bangladesh (around the vast refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar) and in Rakhine State, Myanmar (historic homeland of the Rohingya). As previously reported, an estimated 1.1m. Rohingya have fled persecution in Myanmar since 2017, the majority settling in neighbouring Bangladesh.[4] Despite the UN charging perpetrators of atrocities with ‘tribal cleansing’, Bangladesh has struggled to absorb the pressure of mass migration and failed to persuade the global community to support and protect Rohingya repatriation and their equitable reintegration in Myanmar.[5]

Two aspects of the Rohingya’s plight tend to be overlooked. First, the condition of Rohingya who have remained in Rakhine State. It is estimated that more than 130,000 Rohingya have been incarcerated in tents since ethnically motivated violence re-erupted there in 2012. This is an infringement of the Rohingya’s natural right to ‘return home’: it is also a petty and unjust suppression of their domestic liberty with, it should be noted, severe consequences.[6] The evidence for preventable deaths, and emotional and physical distress, is overwhelming. In late May 2021, nine Rohingya infants died in a spate of chronic diarrhea. Malnutrition and infant mortality are commonplace. Second, the appalling suffering of Rohingya women and girls deserves greater international attention and condemnation. Young and old have been specifically targeted in Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) protests, with female militants among the first to be beaten, jailed, sexually abused, and summarily executed. This has spilled over into Shan and Kachin State, where social and economic hardship has seen many women and girls lured into the hands of Chinese people traffickers and pimps with promises of a new life. Tragically, while the NLD was in power, attempts failed to pass a new – by international standards inadequate – ‘Avoidance of Brutality Against Woman’ law. Lack of regulation has contributed to gender-based violence.[7] Sexual injustice, so widely recognized nowadays internationally, is part and parcel of Rohingya suffering.

ii. If brutality against the Rohingya wasn’t bad enough, the global heartache of the recent COVID-19 pandemic was experienced in Myanmar in a particularly painful way, with the junta turning widespread sickness to their own cynical advantage. Bureau of Health reports recorded (probably conservatively) 17,998 deaths from COVID between March 2020 and October 2021. And yet, by November 2021 only 13% of Myanmar’s population of 54m. had been vaccinated. In many instances, it is said, written endorsement of the junta was a pre-condition of being jabbed (NB. usually only once). The UN Country Team in Myanmar was clear, attacks on healthcare workers compromised the country’s ability to address COVID-19 and prevented the sick from receiving necessary medical treatment. Many suffered and died as a result.

The military’s abuse of healthcare workers during the pandemic and since the coup has often been overlooked. Pharmacists and other medics have been exposed to threats, detention, torture, and death when they have refused to comply with military directives or have treated wounded protesters and opposition forces. An estimated 260 healthcare workers have been attacked, with 20 killed, 76 detained, and more than 600 subject to detention warrants in the nine months following the coup. During the pandemic, many medics were forced (on pain of death, beating or imprisonment) to serve in makeshift COVID clinics. As a result, some ‘shielded’ more against imprisonment than infection.[8] Despite the risks, both before and, perhaps even more so, after this brutal treatment, many in Myanmar’s medical community have played (and continue to play) a key role in the Civil Disobedience Movement, refusing to serve in state hospitals or adhere to the SAC’s demands.[9] For this, many have paid the ultimate price for their country’s freedom and democratic future. The abuse of good offends; even more so when medicine is weaponized and medical workers dehumanized.

iii. Medical workers are not the only group to be singled out for pressure and persecution. Leaving aside the junta’s paranoid attempts to report events to their advantage, by October 2021, the Assistance Association for Political Hostages reported 98 journalists detained, with 46 in custody and 6 in prison. 5 of the latter were charged under Section 505A of the Penal Code, viz. that they had promulgated ‘fake news’ or information that ‘leads to fear’. Predictably, anything deemed disloyal to the junta is censored and its author/s restrained. To illustrate the SAC’s suppression of free speech and the media, on 4 May 2021 the Kachin Channel 74 and the Shan-based Tachileik News Agency were shut down. On the same day, the US journalist Danny Fenster, supervising editor of Frontier Myanmar was jailed.[10] On 12 November 2021 he was sentenced to 11 weeks hard labour and on 15 November expelled from the country. In June 2021, the Ministry of Information instructed broadcasters not to refer to the SAC as a military ‘junta’: to do so risked prosecution. In the weeks following the coup, the military closed regional (and, thus, ethnic) internet use from 1am to 9am. Though this restriction has been lifted, the SAC still blocks internet sites and mobile networks, and disrupts coverage in areas actively (viz. militarily or ideologically) opposed to it.[11] Freedom to voice an opinion in verbal, written or physical form, is a sacred right: its denial an unjust, discriminatory, in Myanmar racial, act of the kind Dr. Martin Luther King Jr fought against.

(The Economic Times)

iv. The complex, multifaceted relationship between Pakistan and Myanmar also warrants close attention. The persisting threat posed by Islamic State in SE Asia has stimulated new diplomatic partnerships. Myanmar and Pakistan have formed a new alliance in light of IS. Military leaders in both countries are committed to close cooperation, despite opposition from many in Pakistan to Myanmar’s treatment of the Rohingya. As an ‘Islamic State,’ with the world’s 5th largest population (ca. 220m.), Pakistan has strong regional, military, and religious ties to Myanmar, and, I would argue, a duty to support efforts to promote peace in Myanmar and just treatment of the Rohingya – and, indeed, all of Myanmar’s citizens. This perspective is largely ignored inside and outside Pakistan. However, at home and abroad, Pakistan’s political and religious elites could do much for Myanmar; not least, to protect its Muslim minorities. This expression of justice and humanitarian concern would, I believe, in the eyes of many around the world, enhance Pakistan’s international standing.

(The Diplomat)

Much could and should also be done to the mutual benefit of Pakistan and Bangladesh by their closer cooperation over the Rohingya. As a Muslim country, Pakistan owes a spiritual debt to the Rohingya who have fled persecution in Myanmar.[12] I believe it could and should use its weight to profile the Rohingya cause and work closely with Bangladesh to share the latter’s burden, in the process strengthening the ties between the two countries.[13] Pakistan’s strong military links to the SAC in Myanmar could also be turned to good ends,[14] with its so-called ‘conventional military politics’ providing a platform for a solution to the Rohingya problem. Pakistan has already promoted Muslim interests globally, particularly in its long-standing dispute over Kashmir and support for the Palestinian cause. Though in the eyes of the world rarely associated with arbitration and mediation, Pakistan can in this instance, I would argue, bolster its reputation and satisfy its own strategic, regional interests.

The so-called ‘all-weather friendship’ and mutually beneficial ‘Eternal Strategic Ties’ that have been established in the recent past between Pakistan and China[15] – including, of course, the latter’s strategic interest in Myanmar’s ports and natural resources[16] – also offer possibilities for Pakistan and for peace in the region; particularly, if Pakistan can broker a deal that benefits the Rohingya and China at the same time. China’s substantial investment in, and dependence on, its ‘Belt and Road’ initiative (BRI), render it vulnerable to leverage.[17] Since Bangladesh has a significant place in China’s BRI project, and is already a beneficiary of other Chinese ‘Mega Projects’, the potential exists for Pakistan to persuade China to see the benefit of stronger links with Bangladesh through supporting its refugee work and repatriation of the Rohingya.[18] A tough ask maybe, but difficult situations require bold solutions. Indeed, the high goals of justice and human flourishing can – indeed, often must – be pursued along the lowly avenues of guile and self-interest!

(VOA News)

v. If a case can be made for Pakistan exerting constructive regional pressure on the SAC and China over the Rohingya, a similar case could – and should – be made for Pakistan’s role globally; in particular, through ASEAN and the UN. To-date, China has refused to vote or vetoed motions that have come before the UN General Assembly and UN Security Council on Myanmar and rehabilitation of the Rohingya. If presented skillfully, I believe ‘Chinese interests’ might be portrayed by Pakistan to the benefit of both countries and to that of Myanmar and the Rohingya. Were this the case, Pakistan’s standing in the region would be enhanced, its relationship to China matured, and China’s own international PR bolstered.[19] Natural justice would suggest that both Beijing and Islamabad have an important role to play in supporting Bangladesh and holding it to account for its response to the Rohingya.[20]

vi. ASEAN has been understandably criticized for its uncoordinated response to the vast numbers of Rohingya refugees pouring out of Myanmar, not only into Bangladesh but into other SE Asian countries, justifying this from its policy of non-interference in the internal affairs of member states. A collective response would have, however, helped to reduce the risks refugees have faced, especially from famine, disease, human trafficking, forced labor, exploitation, and exclusion from basic amenities such as healthcare and education. Though the UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) has been working with ASEAN to protect and support the Rohingya, pressure to honour international and Human Rights law has been largely ineffective.[21] In the terms Dr. Martin Luther King Jr articulated, the Rohingya crisis in Myanmar is a global humanitarian crisis, which requires the attention and effort of the whole international community. The basic rights – indeed, the very existence – of the Rohingya are at stake. To neglect one is to devalue all. My own sense is that Pakistan has a key leadership role to play in the world’s response. Its young Minister of Foreign Affairs Bilawal Bhutto Zardari (b. 1988) and Foreign Secretary, Dr. Asad Majeed Khan, have both expressed their support for the rights of persecuted Muslims around the world and sought to raise awareness of the plight of the Rohingya. But more could be done, perhaps through Pakistan’s Apex Court (Supreme Court).

(Wikipedia)

In June 2022 the UN General Assembly passed a resolution condemning the February coup. In a special session of the UN Human Rights Council in February 2023, a motion was passed that denounced the SAC and its arbitrary detention of protesters and critics. In March 2023, the Council passed a stronger resolution ‘denouncing in the highest terms’ the junta,calling for legal sanctions and restoration of a democratic system of government. The UN General Assembly has also pressed member states to halt arms sales to the junta. However, though Canada, the UK, EU, and US have instituted targeted sanctions against Myanmar’s military leaders and other SAC representatives, groups, and communities dominated by the army, the UN Security Council has to-date failed to secure agreement to sanction all weapons and dual-use machinery trading with Myanmar.[22] In such a situation, it is not only the Rohingya who suffer: the people of Myanmar and peoples of the world are dehumanized by the SAC’s brutal aggression.

Iram Naseer Ahmad, Research Associate[23]

[1] 235 in the House of Representatives and 135 in the House of Nationalities.

[2] NB. Elections were held at the same time for the State and Regional Hluttaws and for the position of Ethnic Affairs Ministers.

[3] They secured 396 seats, with 322 required to form a government.

[4] Cf. Md. S. Sohel, ‘The Rohingya Crisis in Myanmar: Origin and Emergence’, Saudi J. Humanities Soc. Sci 2. 11a (2017).

[5] Cf. J. P. J. Dussich, ‘The Ongoing Genocidal Crisis of the Rohingya Minority in Myanmar’, Journal of Victimology and Victim Justice 1. 1 (2018): 4-24.

[6] Cf. A. Poletti and D. Sicurelli, ‘The Political Economy of the EU Approach to the Rohingya Crisis in Myanmar’, Politics and Governance 10. 1 (2022): 47-57.

[7] Cf. Md S. Islam, ‘Understanding the Rohingya Crisis and the Failure of Human Rights Norm in Myanmar: Possible Policy Responses’, Jadavpur Journal of International Relations 23. 2 (2019): 158-78.

[8] Cf. L. Brooten, S. I. Ashraf, and N. A. Akinro, ‘Traumatized Victims and Mutilated Bodies: Human Rights and the ‘Politics of Immediation’in the Rohingya Crisis of Burma/Myanmar’, International Communication Gazette 77. 8 (2015): 717-34.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Cf. Lu Seng Lamung and Barath Nataraj, ‘Freedom of the Press, the Right of Access to Mass Media: A Case Study of Rohingya/Muslim Crisis in Myanmar’, n.d.

[11] Biswajit Mohanty, ‘Understanding Media Portrayal of Rohingya Refugees’, in Citizenship, Nationalism and Refugeehood of Rohingyas in Southern Asia (Springer, 2020), 97–111.

[12] NB. there are an estimated 300,000 Rohingya living in Pakistan, many having fled the military takeover in Myanmar in 1962. An estimated 55,000 Rohingya live in the Arkanabad suburb of Karachi.

[13] Pakistan’s present economic vulnerability suggests support for Bangladesh might be more plausibly practical than financial.

[14] Cf. Policy Briefngs ISPR, ‘Mayanmar Crisis and Role of Paksitan Military’ (Islamabad, 2021).

[15] NB. this includes a (heavily leveraged) $46 billion, 3000km. infrastructure project, the ‘China-Pakistan Economic Corridor’ (CPEC), from Gwadar part on the Arabian Sea to Xinjiang in SW China. The connectivity established will enable oil, gas and raw materials to pass freely to and from China.

[16] Cf. the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor.

[17] Cf. B. Bland, ‘All Risk, Few Options in Myanmar’ (March 2021): https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/all-risk-few-options-myanmar.

[18] Cf. I.N. Ahmad, ‘Building the Nation Amid Infrastructure; China Pakistan Economic Corridor (Cpec), Dividends and Apprehensions’, American Journal of Economics and Business Management 5. 10 (2022): 19-35.

[19] NB. It is noteworthy – and commendable – that China did not resist the November 2021 UNGA resolution on Myanmar. On the Rohingya crisis, see also A. Trihartono, ‘Myanmar’s Worsening Rohingya Crisis: A Call for Responsibility to Protect and ASEAN’s Response’, in B. McClellan ed., Sustainable Future for Human Security: Society, Cities and Governance (Springer, 2018), 3-16. The plight of the Rohingya has been exacerbated by the fact that the 1951 Refugee Convention is not upheld in law, nor endorsed consistently, in a number of ASEAN states. As a consequnce, the COVID-19 pandemic saw countries closing their borders to fleeing Rohingya. This exacerbated the situation for the Rohingya. Attempts to address the issue at the regional level have been poor, with ASEAN’s Coordinating Centre for Humanitarian Assistance on Disaster Management (AHA Centre) and Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights (AICHR) slow to act and ineffective. On this, see S. N. Parnini, M. R. Othman, and A. S. Ghazali, ‘The Rohingya Refugee Crisis and Bangladesh-Myanmar Relations’, Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 22. 1 (2013): 133-46.

[20] Cf. J. Wuthnow, Chinese Diplomacy and the UN Security Council: Beyond the Veto (Routledge, 2013).

[21] Cf. H. T. Ha and Y. Htut, ‘Rakhine Crisis Challenges ASEAN’s Non-Interference Principle’, Perspective (ISEAS) 70 (2016): 1-8.

[22] Cf. M. M. Islam and M. D. Y. Yunus, ‘Rohingya Refugees at High Risk of COVID-19 in Bangladesh’, The Lancet Global Health 8. 8 (2020): e993-e994.

[23] The writer is Assistant Professor in the Department of Public Administration, Comilla University, Bangladesh, a Research Associate of Oxford House (www.oxfordhouseresearch.com) and is soon to complete doctoral studies at the University of Ghent, Belgium.