I am delighted to introduce the work of our outstanding Argentinian Associate Dr Pablo Baisotti. Pablo is a historian and social scientist (with an MA and PhD from the ancient University of Bologna, Italy), whose multidisciplinary approach to Latin America studies sheds important light on contemporary global issues. There is much here to make one sit up and listen … very carefully.

Few question the reality of a technological revolution since the end of World War II. Indeed, the breadth, depth and speed of change has caught even the most foresighted unprepared. Mobile phones marketed as ‘new’ are, to their creators, already obsolescent. As technology advances, society is forced to change. New electronics impact economies and relationships, warfare and farming. New materials change clothing and camouflage, heating and houses. Communication, information, knowledge, and indeed ‘science’ itself, as the art of empirical analysis, have been and are being reimagined as never before. As Klaus Schwab (b. 1938), Founder and Executive Director of the World Economic Forum said in January 2016 of this ‘fourth Industrial Revolution’:

We stand on the brink of a technological revolution that will fundamentally alter the way we live, work, and relate to one another. In its scale, scope, and complexity, the transformation will be unlike anything humankind has experienced before. We do not yet know just how it will unfold, but one thing is clear: the response to it must be integrated and comprehensive, involving all stakeholders of the global polity, from the public and private sectors to academia and civil society.[1]

Whether this technological revolution will in the end make for a better society and world remains to be seen. One thing is clear, while technologies may have advanced, societies have not. Only the most obtuse or ill-informed would claim democracy and the political process, diplomacy and international relations, Human Rights and the distribution of the world’s resources, are in a better, more equitable and peaceful state than they were fifty years ago, let alone since the first Industrial Revolution in the 18th century. The myth of inexorable human ‘Progress’ is now comprehensively shattered, or so it would seem.

What is the evidence that society at large has failed to keep pace ethically and relationally, conceptually, and even perhaps, intellectually, with the technological sector worldwide? I suggest it is most clearly visible in the self-justifying aggression that characterises many inside and outside the socio-political elite. Present day conflict in Ukraine, Syria, Eastern Turkey, Central Africa, the South China Sea, and in unnumbered smaller clashes, isn’t the cause of aggression, it is merely a symptom of it. At every level, in almost every society, dissent is suppressed, and dissenters mocked, imprisoned, silenced, or ‘cancelled’. From the frontline in the Donbas to the dirty jails of Nicaragua and China, and the supposedly measured Groves of Academy,[2] those who presume to dissent from the prevailing opinion of socio-political elites are withered and wasted by an unbridled spirit of aggression. ‘Peace on earth, good will to men’? I think not. This, too, may not be new under the sun, but it is an unpleasant accompaniment to a world that has become faster, firmer, and more forensic in almost every (other) area of science and technology.

My focus in this Briefing is on the self-interested aggression manifest in rulers and ruled in many parts of the world today. Why has this occurred? Are religious extremism or relativist postmodernism cause or consequence of this new, unpleasant face of 21st century culture? And we can’t exonerate anyone anymore with simplistic rehearsal of liberal historian Lord Acton’s (1834-1902) words: ‘Power tends to corrupt: absolute power corrupts absolutely’. For revisionist views of the nature of ‘power’ – let alone the outdated and obnoxious notion of ‘absolute power’ – make pious platitudes and censorious putdowns part of the problem not clues to a solution. Does history leave lessons to be learned and never to be repeated? Yes, indeed, but it seems history has taught more about how to be aggressive than how not to be. Ethics and self-control, mutual respect, and the arts of effective peacebuilding, aren’t, it seems, historical lessons we choose to learn. Instead, aggression is esteemed above care, image above wisdom, and love of self above love of neighbour. Historic ethical orientation towards the ‘good’ and away from ‘evil’ is conveniently relativised by self-interest into a philosophy of values rooted in what is ‘good for me’, or, in the case of leaders, ‘what seals my grip on power’. Far from reorienting life to a principled pursuit of all that encourages duty, service and the ‘common good’, ethics have become oppressive, inconvenient, old-fashioned, and ultimately self-justifying. Rulers and ruled are complicit. No wonder life is, perhaps as never before – even when a government is in place – ‘nasty, brutish and short’, as English philosopher and political theorist Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) argued in his seminal study Leviathan (1651).

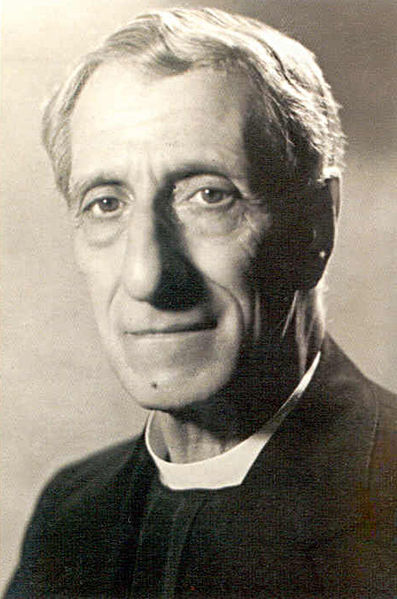

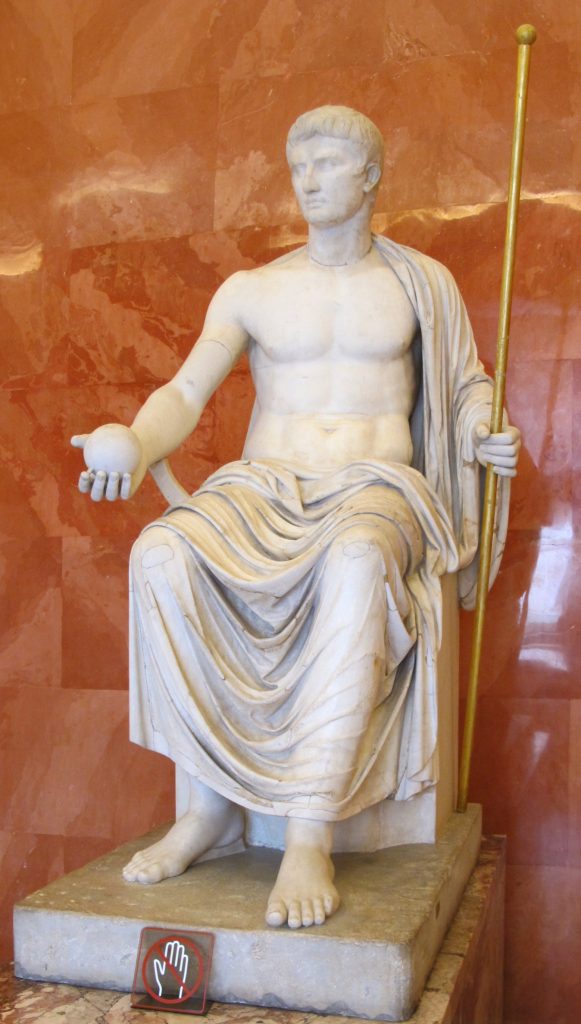

But is this new? Have systems of government and society ever delivered ‘peace on earth’? In 1924, the Italian priest-politician Fr Luigi Sturzo (1871-1959) – an erstwhile ‘clerical socialist’ and courageous proponent of the 19th century, mid-European ‘Christian/Centrist Democratic’ political ideology – penned his trenchant monograph Popolarismo e fascismo. If we imagine perversion of power today to be new, Sturzo’s work disabuses us of the notion. Indeed, he characterises repeated systems of government as founded on various kinds of idolatrous ‘deification’. So, monarchy ‘deified’ the king, liberalism ‘deified’ the individual, democracy the people, syndicalism class, state socialism the state, nationalism the nation. To Sturzo, nationalism, in its quest for the ‘absolute’, embraced the principle of ‘popular sovereignty’ with pantheistic zeal and finality.[3] So, ‘Statism’ had become for a majority the new, neo-religious, orthodoxy.

Though vilified in his day, Sturzo’s analysis has been vindicated by history. Few doubt that in the first half of the 20th century, an ideological privileging of ‘nation state’ and national leaders, effectively displaced the historic role of religious faith and a clerical hierarchy. ‘The people’ – especially in democracies – came to assume a ‘neo-liturgical’ profile as devotees of political idols, leaders became secular demi-gods, and traditional religious iconography was replaced by political meetings, manifestos, and carefully crafted propaganda.

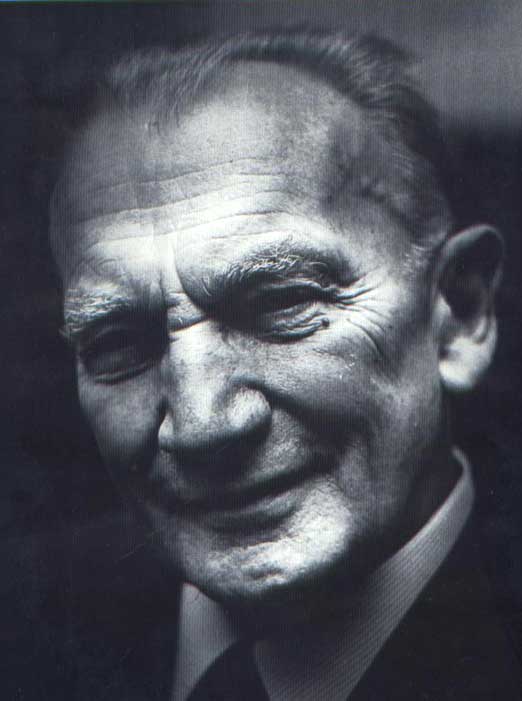

Another prophetic voice in the mid-20th-century was the Swiss ecumenist Adolf Keller (1872-1963).[4] In his Church and State on the European Continent (1936), Keller describes the new totalitarian ‘religions’ of Bolshevism, Fascism and Nazism as leading an ideological revolution against the cultural mores of Christendom.[5] By sacralising and deifying the State, Keller argues, they created a new secularised (viz. religion-less) civilization. In this new reality, the State enshrines and enacts a new religion-less ‘myth’. With quasi divine power, it claims and exercises sovereign rights over the minds, hearts, and bodies of citizens. And, like a grotesque giant, it bestows on its political creation – a messianic hero and Superman leader – the right to expect, and power to require, unquestioning trust and devotion.[6]

Has historical wisdom taught us nothing? I fear not. Even a cursory glance at the way Putin and Xi, Kim Jong-un and a raft of other contemporary dictators (and even more troublingly, perhaps, supposedly ‘democratic’ leaders) perceive their role, demand absolute allegiance, and exercise unaccountable power, suggests Sturzo, Keller and others who have written of the ‘sacralization’ of the secular state, are on to something important. Fear, fanaticism, and an aura of secular (and often self-righteous) religiosity – if not mystical infallibility – haunt the corridors of power. All too often ruler and ruled are complicit in condemning dissent. Enemy guilt and the absolute right and responsibility of the ruler and ruling cadre to purge dissent and purify the nation, are cast in salvific terms as the victory of a perverted ‘Good’ (if not, ‘god’) over unrighteous ‘Evil’.[7] Hypocrisy be damned: the powerful know best. This is the milieu in which aggression reigns and the intimidation of rivals thrives.

Another acute observer of the transformation of Western culture was the Dutch missionary historian Hendrik Kraemer (1888-1965). In his report to the 1938 International Missionary Council in Madras, Kramer spoke passionately and perceptively of the pseudo-absolutes (Sturzo’s ‘false gods’) humans create when they abandon belief in God. Secular atheism fills the void with another ‘divine word’[8] in which nation, race, classlessness, and other political ideologies, are endowed with a ‘sacred’ and/or ‘eternal’ quality. To Kraemer (parodying Jesus), ‘Man does not live by relativism alone, but by every word that proceeds from the mouth of the powerful’ (cf. Matthew 4.4).

But Kraemer takes his argument one stage further. Far from statist secularism destroying faith, popular piety and the paraphernalia of religious doctrines and institutions, he argues, it looks to religious leaders past and present for validation of its identity and power. This isn’t entirely new, of course, politics and politicians have often co-opted religion. What is new, Kraemer claims, is the cynical adoption of religious categories and institutions by those who do not believe in them and translation of their (priestly) power and (prophetic) authority onto the (new, secular) State and those who govern. But to Kraemer, crucially, the apparent triumph of ‘secular man’ will be – or, perhaps, already has been – short-lived. Life without the living God means death with a lifeless idol. To cancel God is to destroy creation. Though universalist idealism and absolutist humanism flourished in the aftermath of World War I, Kraemer is clear, atheism gave birth to new ‘gods’, the gods of ‘self’ and the State, of institutional ‘religion’ and secular piety, with their tyrannical claims on humanity; for, as human constructs, self-made ‘religions’ are always empty, false, and very dangerous.

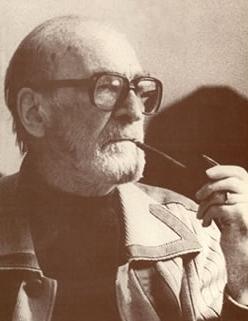

Discussion and construction of ‘sacral’ States continued in the 1960s and 1970s. Key voices at the time were, among others, the Italian sociologist Sabino Acquaviva (1929-2015) and the Romanian historian of religions Mircea Eliade (1907-1986). Acquaviva studied the ‘new religions’ (as he called them) of the interwar years. He found there a strong ‘hierophanic’ style (viz. manifesting the divine) with their own vibrant myths and intense rituals (esp. at funerals).[9] In the early 1960s, Eliade also spoke of the rise of ‘new religions’, when the historic ‘sacred’ is subsumed by the contemporary ‘secular’ or ‘profane’.[10] To Eliade, this perverted and perverting ‘sacralization of politics’ blossomed in fascism, Nazism, and Stalinism. Like new ‘churches’, absolutist ideologies propagated ‘non-negotiable’ truth and a ‘sacralized’ human society.[11] Like Sturzo, Keller and Kraemer, Acquaviva and Eliade give us categories in which to describe the shift in political discourse, propaganda, and self-confident aspiration, we witness today in Putin and other crazed prophets of political apocalyptic.

Throughout the 1970s other ‘marriages of convenience’ were contracted between new political ideologies and religion. In Israel, the right-wing Likud (lit. ‘Consolidation’) party, formed by Menachem Begin (1913-1992) and Ariel Sharon (1928-2014) in September 1973, won a landslide victory in 1977. In the Arab world, the Organization of the Islamic Conference – later, the 57 member OIC [Organization of Islamic Cooperation] – was created in 1973 as a religious rival to pan-Arab associations led by the charismatic Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser (1918-1970; Pres. 1955-1970) and the Syrian intellectual Michel Aflaq (1910-1989). In Iran, the 1979 Islamic Revolution, overseen by the religiously conservative Ayatollah Khomeini (1902-1989; Supreme Leader 1979-1989), rejected the secular ethos of the ruling Pahlevi family.[12] Throughout the 1970s, with totalitarian brutality and cultural aggression, despotic leaders from Daniel Ortega (b. 1945; Leader 1979-1990, Pres. 2007-present) in Nicaragua to Enver Hoxha (1908-1985; 1st Sec. 1941-1945, Leader 1945-1985) in Albania, Fidel Castro (1926-2016; PM 1959-1976; Pres. 1976-2006) in Cuba to Mao Zedong (1893-1976; Chairman 1949-1976) in China, not only suppressed religion but suborned its power, creating a neo-religious myth to defend and justify their actions and position. This ‘sacralizing’ of the secular political space helps explain the zeal and vision that drives President Putin’s ‘Orthodox’ crusade in Ukraine against the ‘evils’ of the West.

We will return to Putin. For now, note how religion has never been expunged from society and history; albeit revisionist narratives have often recast its leaders and legacy in negative (often imperialistic) terms. There are many explanations of the durability of religion and piety. To Austrian American sociologist Peter Berger (1929-2017) the persistence – indeed, growth – of faith’s presence in societies worldwide reflects the intensification of conviction when exposed to competition. In a plural, ‘market situation’ faiths compete internally and externally, and, in the process define and refine one another.[13] If this sheds light on the intra-societal dynamics of religion, faith traditions have also – and always – had a role to play in differentiating between states and determining the way they relate diplomatically. In short, internationalism hasn’t and doesn’t kill religion, it focuses faith convictions and buttresses patriotism. More than this, to the Swiss Roman Catholic priest-theologian Hans Küng (1928-2021) and German theologian Karl-Josef Kuschel (b. 1948), who wrote of the proliferation of religion and religiosity in the 1990s, a chaotic à la carte of spiritual options gives unscrupulous dictators (and sycophantic officials) a basis to reinvent themselves as ‘religious’ beings or ciphers of popular religious sensibility.[14] Hence, the well-springs of religious integrity were contaminated, and the language and practice of faith abused.

According to IDEA (International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance), in 2019 there were 32 dictatorships in the world (viz. in 20% of countries a ruler suppressed political and social plurality).[15] In other words, the potential for religion to be co-opted or coerced by states worldwide is considerable. From the ruling Saud family in Saudi Arabia (from 1932) to the tyrannical Venezuelan dictators Hugo Chávez (1954-2013; Pres. 1999-2013) and his successor Nicolás Maduro Moros (b. 1962; Pres. 2013-present), ‘religion’ has provided the conceptual framework and rationale for state identity and Presidential power. So, the ‘sacralizing’ of secular power and justification of aggression are instrumentalised.[16]

Vladimir Putin’s (self-)transformation from FSS operative to Prime Minister to perpetual President of Russia, should be seen in this light. His expansionist vision and military action in Chechnya (1994, 1999), Georgia (2008), Crimea (2014), Syria (2015) and Ukraine (from February 2022) have been increasingly explicitly justified as a socio-spiritual crusade to recover ‘Russian’ values (in the face of Western corruption) and restore ancient Russia’s lands. Appeal to the (embarrassingly complicit) Russian Orthodox Church is intended to sanction and ‘sacralize’ his ruthless secular aims. Whatever his ‘values’, they hardly bear close moral scrutiny. The legitimate concern of many observers is that success in Ukraine may harden the expansionist resolve of Putin’s geopolitical cronies in Beijing, Pyongyang, Tehran and Yangon,[17] in all of whom aggression is the lifeblood of (their) political economy.

I want to end with what I see to be three caveats for critical observers of the ‘sacralization’ of state power in the world today.

First, even in its most general definition as ‘a willing pluralising (and protection) of public opinion’, democracy worldwide is under threat as never before today. Whether it be in the unaccountable imposition of government regulations during the COVID pandemic (and, in some cases, their subsequent perpetuation) or populist aggression behind self-confident woke-ism, the rights of an individual to believe and speak freely are being eroded. Those who ‘cancel’ others risk ‘canonising’ their views and ‘demonizing’ others. Human, secular values are thereby accorded the non-negotiable veracity of ‘divine’ injunctions. We do not need to look far to find intellectual ‘dictatorships’ ruling complicit Western cultures.

Second, technology is an inadequate buttress against the rising tide of post-ethical culture. Political and ideological absolutism readily inhabit the space vacated by faith and morality. The issue today is not only that ‘Knowledge is power’ but that ‘Might is (as always) right’. Those with power to make rules, influence opinion and shape lives, do so. The majority of us are merely playthings of others’ ambitions, agendas, foibles and fears. Yes, there are ways to de-sacralize secular power and recover authentic religiosity and spirituality, but, as Jesus warned, ‘the way is hard and gate narrow’ (Matthew 7. 13-14). The post-ethical culture that currently prevails in many countries privileges private opinion until it dissents from the will of the powerful. Dissenters beware. As Küng urged, we must renew our commitment to an ethics that pursues ‘the common good’ while preserving the rights and dignity of an individual.[18]

Third, as we have seen, history provides intellectual resources and substantial cautions to counter the secular abuse of sacred things. The German political philosopher Karl Marx (1818-1883) knew the power of authentic faith when he dubbed religion ‘the opium of the people’. Ironically, perhaps, his atheistic heirs have discovered the same truth and looked to religious language, sentiment, and iconography to validate their positions and opinions. Faced by a world threatened on every side by ‘war and the rumour of wars’ (Matthew 24.6), that will use without conscience or a sense of ultimate accountability the fearsome new technologies it devises, the need for ‘good’ people to resist ‘evil’ has arguably never been greater. To know that authentic religion has been wilfully co-opted and cynically perverted is a good starting point. But, as ever, ethics includes action: intention is never enough. Societies can redress the balance of power and keep in step with the Technological Revolution if, and when, they open the door to a comprehensive revaluation of prevailing values and willing recovery of transcendent virtues. Aggression cannot, surely, become the face of modern ‘civilization’.

Dr Pablo Baisotti – Oxford House Associate

[1] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/01/the-fourth-industrial-revolution-what-it-means-and-how-to-respond; accessed 19 January 2022.

[2] Whatever one thinks of the Canadian Clinical Psychologist and controversial media personality Professor Jordan Peterson (b. 1962), he is not alone in claiming ‘woke ideology’, ‘political correctness’ and/or a ‘cancel culture’ have eroded the credibility and confidence of academic freedom and the democratic principle of ‘free speech’. On this, see: https://nationalpost.com/opinion/jordan-peterson-why-i-am-no-longer-a-tenured-professor-at-the-university-of-toronto; accessed 19 December 2022. Also, on the aim of ‘woke ideology’ or ‘wokism’, as a branch of the extreme left that seeks (in the name of social justice) to ‘cancel’, fine and silence contrary opinions: see https://www.religionenlibertad.com/secciones/1/287/tag/woke.html; accessed 19 December 2022.

[3] Cf. Sturzo, L., Popolarismo e Fascismo (Torino, 1924).

[4] Keller was a Swiss Protestant theologian, professor, and Secretary-General of the European Central Office for Ecclesiastical Aid.

[5] Cf. Keller, A., 1936. Church and State on the European Continent (London, 1936).

[6] Gentile, E., and R. Mallett, ‘The Sacralisation of politics’, Totalitarian Movements and Political Religion 1.1 (2000).

[7] The myths were tied to religious and Christian conceptions of the world but were ‘secularized’, viz. they made connections with a pagan past and hope-filled future. Such myths became ‘real’ through tangible public symbols. On this, cf. Mosse, G., La nazionalizzazione delle masse (Bologna, 2011); Cavanaugh, W., ‘The Myth of the State as Savior’,in W. Cavanaugh, Theopolitical Imagination (Edinburgh, 2002; Gray, J., Black Mass (New York, 2008; Griffin, R., R. Mallett and J. Tortorice (eds), The sacred in Twentieth Century Politics (Basingstoke, 2008).

[8] Cf. Kraemer, H., The Christian Message in a non–Christian World (London, 1938).

[9] Cf. Acquaviva, S., L’eclissi del sacro nella vita industriale, Ed. Di Comunità (Milano, 1961).

[10] Cf. Mircea, E., Lo sagrado y lo profano (Madrid, 1981, 4th ed.).

[11] Cf. Gentile, E., Le religioni della politica. Fra democrazie e totalitarismi (Bari, 2001).

[12] N.B. The Pahlevi drew inspiration from the Turkish leader Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s (1881-1938; Pres. 1923-1938) in their attempt to turn Iran into a modern, Westernized state. On this, Petschen, S., ‘La nueva presencia de la religión en la política internacional: una dimensión a tener en cuenta en una alianza de civilizaciones occidental e islámica’ (17 October 2007); https://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/documento-de-trabajo/la-nueva-presencia-de-la-religion-en-la-politica-internacional-una-dimension-a-tener-en-cuenta-en-una-alianza-de-civilizaciones-occidental-e-islamica-dt; accessed 1 January 2023.

[13] Cf. Berger, P., A Rumor of Angels: Modern Society and the Rediscovery of the Supernatural (New York, 1969).

[14] Cf. Küng, H., and K-J., Hacia una ética mundial (Madrid, 1994).

[15] Cf. IDEA’s report The Global State of Democracy 2019.

[16] Cf. Varela, A., ‘Estos son los 32 países que todavía viven bajo una dictadura, que gobiernan a un 28% de la población mundial’, Business Insider (8 December 2019): https://www.businessinsider.es/estos-son-32-paises-todavia-viven-dictadura-539885; accessed 1 January 2023. NB. The IDEA report lists Russia as an ‘authoritarian democracy’ (viz. not a dictatorship): The Economist’s Democracy Index identifies her (with 52 other states) as a ‘dictatorship’.

[17] Salazar, J., Putin: gánster, tirano y terrorista (1 November 2022: https://ellibero.cl/opinion/putin-ganster-tirano-y-terrorista/ ; accessed 2 January 2023.

[18] Cf. Küng, H., La crisis económica global hace necesaria una ética global (Madrid, 2011).