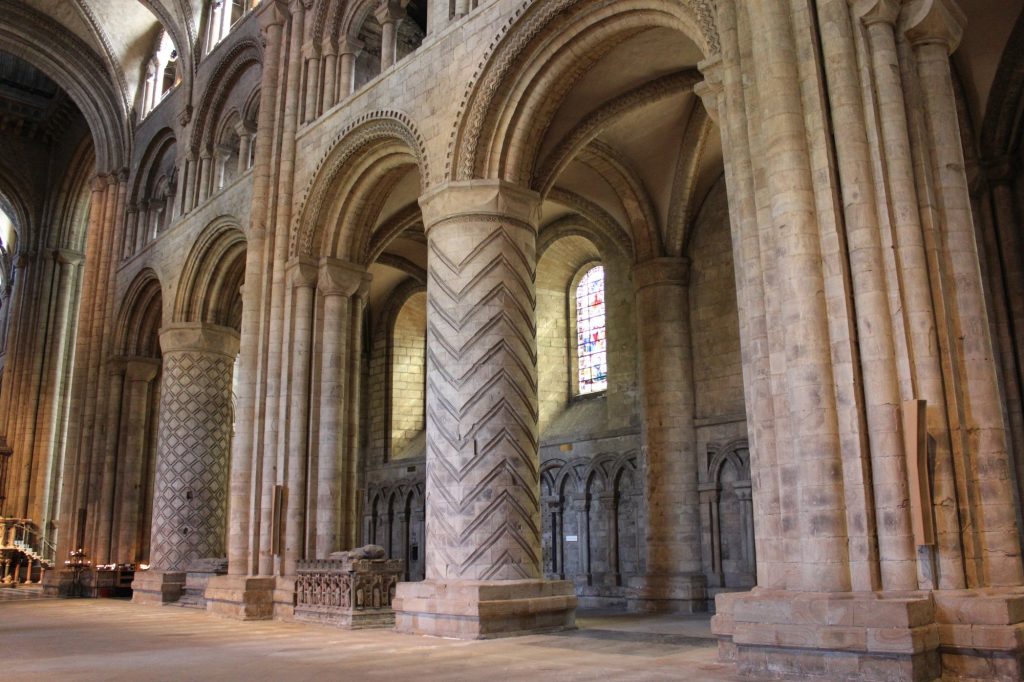

It was late-August 1976 when I first visited Durham Cathedral, poet Sir Walter Scott’s ‘Half church of God, half castle ‘gainst the Scot’. The pillars of the Norman nave (built 1093-1133) took my breath away. As round as they are tall (6.6m), with deep cut geometrical patterns, the pillars seem to set a standard for all others … but they are hollow.

By racoles – Monks Protesting in Burma, CC BY 2.0

A year-ago today, I was winding up a ten day visit to Yangon, Myanmar. I sat on a rattan sofa in a charming open-air café looking over palm-lined Kandawgyi Lake and General Aung San Park. As I walked back to my hotel in the rush hour, the monumental Shwe Dagon or ‘Golden Pagoda’ (officially Shwedagon Zedi Daw), the oldest and most sacred pagoda in southern Myanmar, shone bright in the setting sun. I had earlier ascended, through a flotilla of bright-robed Buddhist monks and a mass of awestruck visitors, the many tiers of steps to the central platform on Singuttara Hill, where the gold-plated ‘stupa’ rises 170m above sea level to dominate the city skyline. How different from my visit in October 2007, at the height of the Saffron Revolution. The city was all but a ghost town. Young monks faced off against scowling soldiers. The ‘Golden Pagoda’ was the epicentre of protest: purportedly against the military junta’s removal of fuel subsidies; in reality, against all it stood for. With the 6pm curfew the heavy gates of my hotel nearby shut tight. BBC 24 reported from the Thai border what was happening outside. Premier League soccer was a welcome evening distraction! I climbed to the platform of the ‘Golden Pagoda’ then a solitary figure in a tense city. How Yangon has changed. The hopes of its citizens raised, fulfilled and dashed. The Nobel Prize winning ‘pillar’ of pro-democracy protest, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi (b. 1945), once canonised by the West as the embodiment of democratic expectation, is now the oddly named and ambivalently viewed State Counsellor of Myanmar, her standing shaken by an earthquake of criticism at home and abroad for taking Chinese bribes and ignoring Rohinga persecution. While the old ‘pillars’ of the military elite stand defiant like the ‘Golden Pagoda’ against the ravages of time, corruption and socio-political change. Pillars maybe, but hollow pillars all.

By Bjørn Christian Tørrissen – Own work by uploader, http://bjornfree.com/, CC BY-SA 4.0

The term ‘pillar of society’ suggests a decent, reliable, hard-working, respected type, who sets the well-being of others above their own. To such, caps are doffed, seats assigned and access to clubs made easy. In the ancient world, to be a ‘pillar of society’ was precisely that, to be etched in stone on a column by a road. Like a village War Memorial in Britain, passers-by were to see and remember. Apostles Peter, James, and John are designated ‘pillars of the church’ (Galatians 2.9) as a mark of their authority, legacy and exemplary faith. Medieval tradition in the West preserves a positive meaning for ‘pillar of society’. In some Arabic poetry, however, we see a shift. Though the madīḥ (a poet’s tribute to himself or his tribe) may praise kings as ‘pillars of society’, ciphers of divine power and satisfiers of social need, to the Zaidiyyah (a Shia sect) the king is a mortal seduced by the mirage of power. In short, position does not equate to common-sense, faith, self-awareness, humility, or integrity! Over time Western respect for (self-professed or presumed) ‘pillars of society’ wanes. So, Shylock’s speech to the judge, in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice (Ac. 4 Sc. 1, l. 227f.), is tongue in cheek:

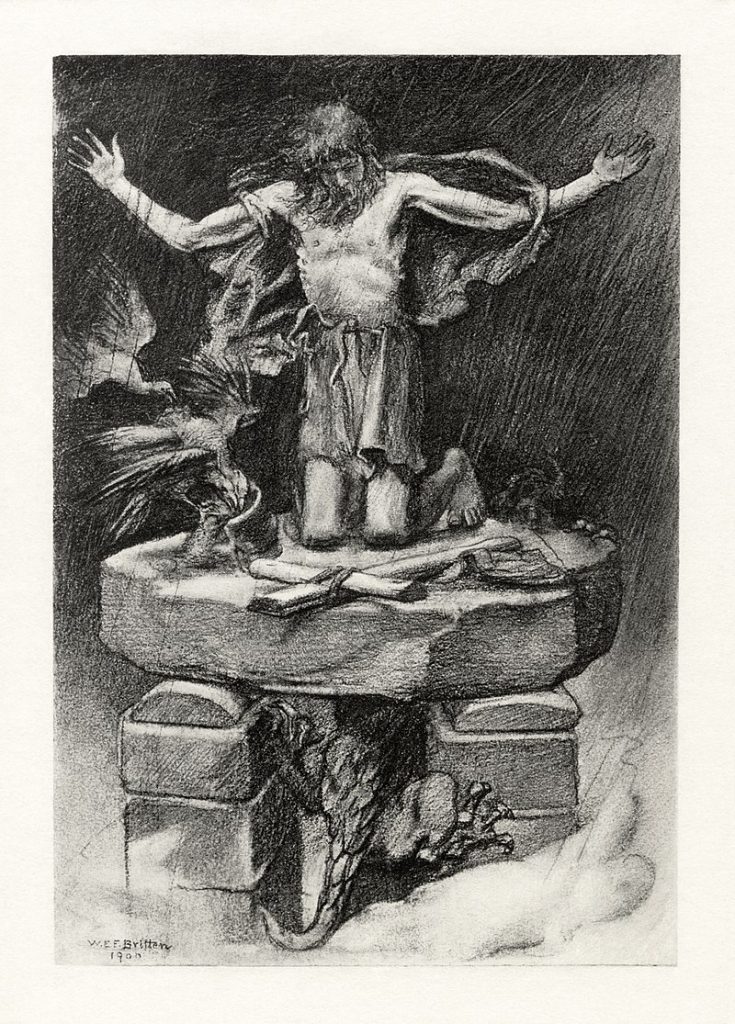

By William Edward Frank Britten (1848–1916)

It doth appear you are a worthy judge.

You know the law. Your exposition

Hath been most sound. I charge you by the law,

Whereof you are a well-deserving pillar,

Proceed to judgment.

To the New Zealand-British lexicographer Eric Partridge (1894-1979), by 1800 ‘pillar of society’ connotes a drab dresser with a dull life more than the hero of yesteryear. Like the stump of pillar near Aleppo, Syria, on which Simon of Stylites (ca. 390-459) sat and preached to the tens of thousands who sought him out, there is little left of most ‘pillars’ today. Myanmar is not the only place where ‘pillars’ have been shaken, worn down and hollowed out by criticism, compromise, corruption and scandal.

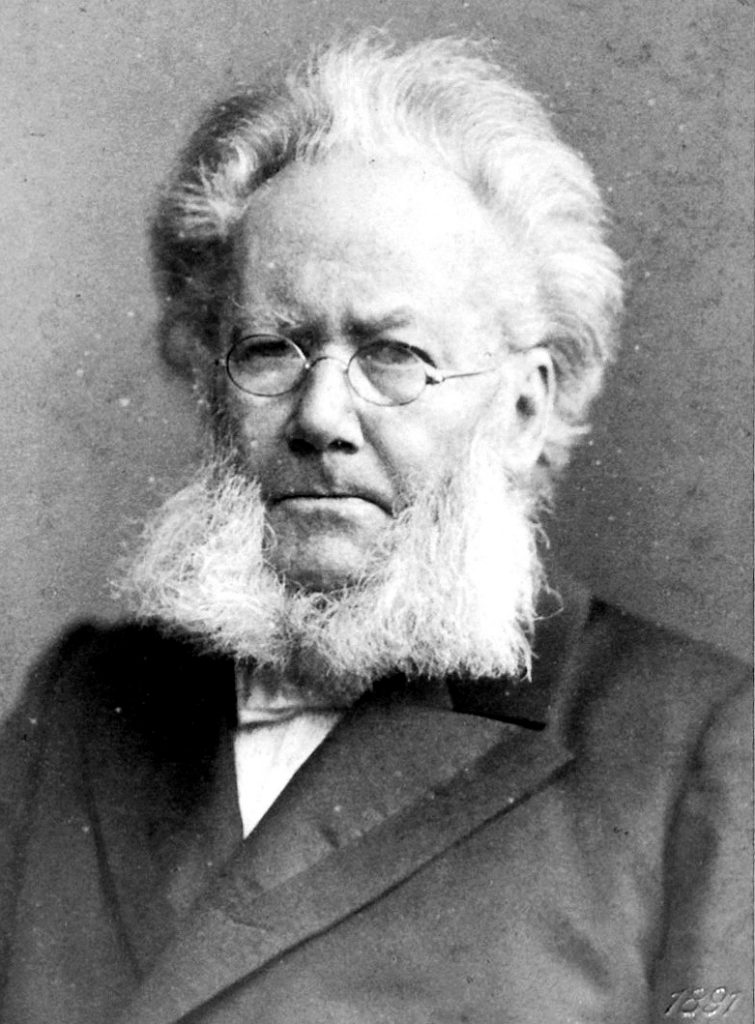

By Julius Cornelius Schaarwächter – Galerie Bassenge

As if to seal a shift in meaning and the progressive erosion of public confidence in individuals, in 1877 the influential Norwegian dramatist Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906) wrote a play entitled Samfundets støtter, Lit. The Pillars of Society. It was the first of Ibsen’s plays performed in London (Quicksands,1880), and like his other work did much to inspire ‘realist modernism’ in writers such as George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950), Oscar Wilde (1854-1900), James Joyce (1882-1941), Eugene O’Neill (1888-1953) and Arthur Miller (1915-2005). Based, like many of his plays, as much on his life in a wealthy shipping family as his despair with Norwegian (indeed, modern) society, the play tells a complex tale about a respected, but ambitious, businessman from an old shipping dynasty, Karstin Bernick. Bernick, we discover, wants to enhance his reputation, and make a financial killing, through a new railway project. His plans face derailment when his brother-in-law, Johan Tønnesen, returns unexpectedly from exile in the US, bringing with him the truth of Bernick’s affair with an actress Tønnesen is assumed to have had a liaison with (to hide which, people think, he fled Norway). In fact, Tønnesen had taken the blame for his brother-in-law’s behaviour to protect the Bernick business. Back in Norway, Tønnesen falls in love with Dina Dorf, the impoverished daughter of said actress, who lives (in ignorance) off Bernick charity. Tønnesen presses Bernick to tell Dina the truth. He refuses. Declaring that he intends to end his US sojourn and return to marry Dina, Tønnesen prepares to sail on the Indian Girl, a ship Bernick murderously ensures his dockyard repairs patchily to protect his reputation and railway scheme. With more implausibility than most critics can accept (!), at the eleventh hour, Tønnesen and Dina take another boat, Bernick’s young son stows away on the Indian Girl (but is rescued when the boat is hailed by the conscious-stricken foreman who oversaw the shoddy repairs), Bernick owns up to (most of) his faults, is forgiven by his wife and hailed by his local community. With biting irony, Ibsen asks, Are so-called ‘pillars of society’ all they seem, or claim to be, and really worthy of our respect? Or perhaps he hopes we can be shocked into morality by the failures of others.

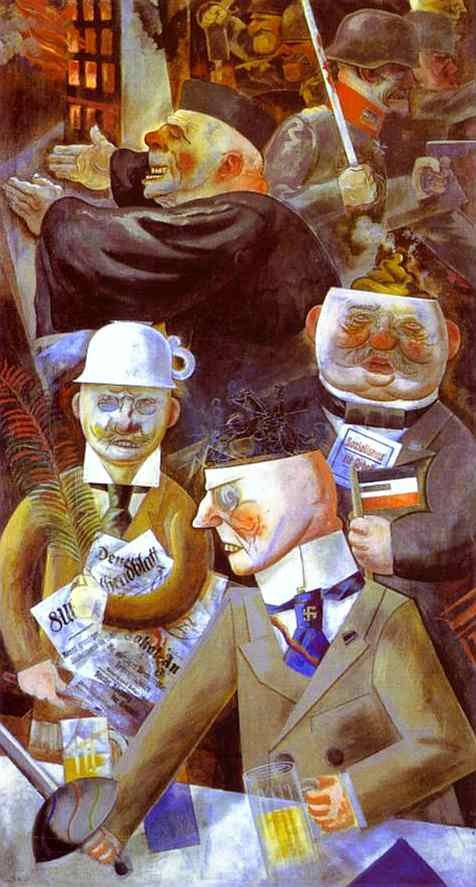

Ibsen’s work watered seeds of suspicion sown in previous generations, but he spawned many more. The German American ‘dadaist’ artist George Grosz (1893-1959) took the title of Ibsen’s work for his ghoulish 1926 caricature of elite figures who supported Fascism. An oafish aristocrat in the foreground, with misty monocle and swastika emblazoned necktie, has a stein of beer in one hand, a useless foil in the other, and a war-horse rising from his skull. Journalist-businessman and politician Alfred Hugenberg (1865-1951) sits to his left like a numbskull, with newspaper and bloodied palm branch in his hands and a chamber-pot on his head. To the right, the first German President Friedrich Ebert (1871-1925; Pres. 1919-25) holds a national flag and the pamphlet ‘Socialism must work’, while steaming dung hangs around his head. Through a window a city burns, while a pro-Nazi cleric preaches an empty gospel of peace. To honour Grosz’s timely warning, the picture hangs in the Nationalgalerie Berlin … lest we all forget. It is a work reproduceable around the world with other claimed, or claiming ‘pillars of society’, who are, in T.S. Eliot’s (1888-1965) poetry, mere ‘hollow men’; or so Ibsen and Grosz would warn.

While application of ‘pillar of society’ to individuals has waned, its institutional use has gone from strength to strength. Traceable to the medieval idea of ‘three estates’ of a realm (viz. clergy, nobility, and peasantry or, later, bourgeoisie), modern usage speaks of the three ‘pillars’ or ‘estates’ that define and preserve the ‘separation of powers’ in a democracy (viz. the legislature, administration or executive, and judiciary). Society is built on these three pillars, with the ‘fourth estate’ (in European languages often translated ‘fourth power’) being no longer as of old rural commoners but the media in all its many forms. Alongside this socio-political usage, we find the ‘five pillars of Islam’, viz. profession of faith (shahada), prayer (salat), almsgiving (zakat), fasting (swam) and pilgrimage (hajj). Likewise, ‘the three pillars of catholic faith’ (the Bible, Tradition and the Church’s Magisterium), ‘the four pillars of Catholic life’ (faith, liturgy/the sacraments, life in Christ and prayer) and ‘the seven pillars of catholic spirituality’ and social teaching (viz. the life and dignity of every person; the call to family, community, and participation; rights and responsibilities; the divine option for the poor and vulnerable; the dignity of work and the rights of workers; solidarity; and care for God’s creation). To some, we should add ‘the three pillars’ of sustainability (viz. social equity, economic viability, environmental protection) or corporate sustainability (viz. people, profits and planet). While individual ‘pillars’ (leaders, generals, businessmen and sound citizens) may be shaken by scandal, suspicion, media-driven criticism and secular cynicism, these institutional ‘pillars of society’ hold firm – or so, it seems, we are meant to believe.

In a week that has seen the transfer of Presidential power to Joe Biden (b. 1942) we have an opportunity to reflect on the extent to which the stability, or instability, of America, or any other country, depends on one person. Can they be ‘a pillar of society’? Or are Ibsen and Grosz right to urge a more cynical view of leaders and leadership? Three thoughts before I end.

First, Zaidiyyah spirituality is right to focus our view of power not on officeholders but on the agencies, human and divine, that sanction and endorse them. If our systems and visions depend on individuals, they will, by definition (and mortality!), falter and fail. Democracy in Myanmar depends on more than ‘the Lady’, Aung San Suu Kyi: it must do to succeed. President Biden will be crushed – like, perhaps, his predecessor – if, or when, he takes power into his own hands and shoulders responsibility alone. Solidarity in and between every ‘estate’, or ‘pillar of society’, is sound socio-political and spiritual wisdom. And, woe betide our Western liberal democracies if we allow the ‘Fourth Estate’ to dominate the others.

Second, Ibsen and Grosz prompt a push-back to the cynicism they seek to engender. After all, is it true that every worthy person is hiding some dirty secret, as a news hungry media would want us to believe? And is it wrong to venerate as ‘pillars’ and ‘saints’ in society those whose life and virtue transcend their time and locale? Are all pillars ‘hollow? There are more ‘good’ people like Ibsen’s Tønnesen than we perhaps allow ourselves to believe. To reject the fine and excellent is to be condemned to the average, unimpressive and eminently forgettable. Thank God, virtue and the virtuous are alive and well in COVID-ridden communities today.

By AgnosticPreachersKid – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

Last, as I walked the dusty road to my hotel in Yangon a year ago, past simply lit stalls serving tasty morsels to locals and travellers alike, I was reminded ‘pillars of society’ may not be the great and good: they are ‘the salt of the earth’, who in hearth and home, workplace and school, factory and food processing plant do – and go on doing – the ‘good’ that fills the lives around them with energy, humour, joy, value and a sense of purpose. They are the ‘pillars’ of most societies; rough-hewn and less impressive than those in Durham Cathedral – but not hollowed out by cynicism, anger and false aspiration. To such glorious unknowns we should in truth still doff our cap, assign a seat, and open access to the places and spaces they deserve. For these are surely they who ‘walk in the ways of good men [and women]’ (Proverbs 2.20).

Christopher Hancock, Director