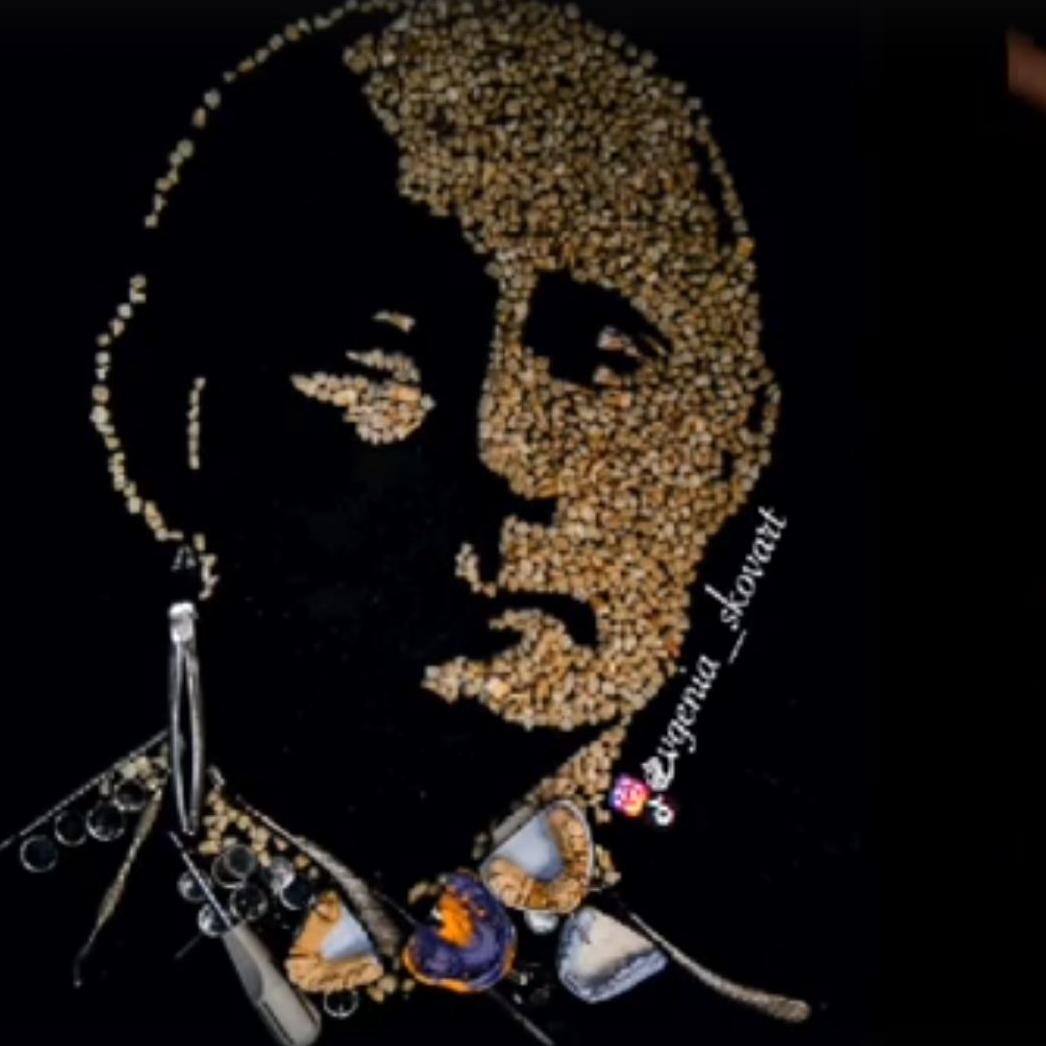

On 1 June 2021, The Times correspondent Tom Parfitt reported on a portrait of President Vladimir Putin (b. 1952; Pres. 1999-2000, 2000-2008, 2012-present) by the Russian artist Yevgeniya Khaybullina. The portrait is striking. It is constructed out of five hundred teeth (some false!) the artist had collected from a dentist in her hometown of Ufa, capital of the Republic of Bashkortostan. Purportedly an ironic response to Putin’s Trumpian claim that he would ‘knock out the teeth’ of anyone who tried to annex Siberia, Khaybullina’s work is a timely reminder of the Russian premier’s original warning: ‘Everyone wants to “bite” us somewhere or “bite off” something of ours, but they should know that we will knock out the teeth of all of them so that they aren’t able to bite.’ To an ex-KGB agent, tough talk and tougher actions are the only language the world understands: no matter what image this projects of Russia and the Russian people as a whole. Perhaps to some, this is how they wish to be seen and their country portrayed, to others not so much. Leaders are not the only image a nation may want to honour. Other portraits matter. Other people matter.

Two weeks ago, the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC announced the honorees for this year’s ‘Portrait of a Nation Award’. Inaugurated in 2015, the award celebrates people who have ‘made a transformative contribution to the United States and its people across numerous fields of endeavour ranging from the arts and sciences to sports and humanitarianism’. Previous honorees include the singer-songwriter Aretha Franklin, designer Maya Lin, former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, film director Spike Lee, entrepreneur Jeff Bezos, AIDS expert Dr David D. Ho, and the iconic Vogue editor Anna Wintour. This year’s recipients include humanitarian chef José Andrés (founder of World Central Kitchen), lead scientist in the fight against COVID, Dr Antony Fauci (Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIAID) and tennis superstars Venus and Serena Williams. As the Director of the National Portrait Gallery, Kim Sajet, said of the award and the honorees: ‘[They are] an expression of gratitude for the leaders in our country who have made a difference … continue to advocate for a better future … [and] use their voices to care for and lift up others.’ She adds, ‘The Portrait of a Nation Award reminds us that history is living and the choices people make have an impact on the nation’s legacy.’ There are no teeth or bite here, and quite different types of ‘leaders’, but an equally solemn warning, ‘the choices people make have an impact on a [the] nation’s legacy’. Indeed, the choices leaders make can shape the world, our world, not just theirs.

Portraits and portraiture are famously controversial. Historically cast in stone, metal, clay, or plaster, and later in various forms of dye, pigment, oil and watercolour, portraiture has been transformed since the invention of photography in the mid-19th century. A May 2021 article in Format magazine is entitled ‘Ten Types of Portrait Photography you need in your repertoire’. I fear my repertoire is distinctly deficient! Photographycourse.net goes further, listing eleven types of portrait photograph: traditional, family and group, formal, lifestyle, conceptual, environmental, candid, glamour, surreal, abstract and close-up. You probably know all this: to a happy amateur snapper like me, it’s overwhelming! But, of course, it’s nothing very new. From of old, portraits have been constructed from different materials for different purposes, and, as Khaybullina’s portrait of Putin reminds us, very often to make a point, whether or not the sitter appreciates it.

In May 2021, the National Portrait Gallery in London published Hold Still: A Portrait of our Nation in 2020. On a different tack from the Smithsonian ‘Portrait of a Nation Award’, the book is the fruit of a project, spearheaded by the Duchess of Cambridge, to capture in 100 images life in lockdown between May and June 2020. 31,000 pictures were submitted, with the final selection focussing on three themes, Heroes and Helpers, Your New Normal and Acts of Kindness. No teeth or biting here, just personal expressions of tragedy and triumph, of humour and loss, of resilience, illness and bereavement. Here are birthday parties and funerals, healthcare workers and the elderly, darkness and unexpected light. Proceeds from the book will be split between the National Portrait Gallery and mental health charity Mind. The portrait of a nation need not be grand to be great, nor tough to win. In the simplest acts of human kindness, as Hold Still records, lie seeds of socio-political and personal renewal. No great controversy here, you might say.

With another royal patroness (Her Highness Sheikha Shamsa bint Hamdan Al Nahyan), Abu Dhabi hosts the UAE’s 50th anniversary exhibition Portrait of a Nation II: Beyond Narratives from 21 January to 16 April 2022. Building on the opening of the Louvre Abu Dhabi in late-2017 and recent explosion of art in the Gulf (after its demise in Egypt post-Arab Spring and evisceration in Syria during the Civil War), this event interweaves a nation’s story with its artistic life. Artists past and present celebrate the evolution of the UAE and its art in talks, workshops, painting, photography, 3D installations and audio-visual displays. The event’s organisers are clear: it is more than a traditional art exhibition ‘capturing the spirit of the UAE art scene’s past, present and future’. No great controversy here either, you might say, although to some the event is more an exercise in national PR than study of the finer points of modern Arab. As a critic of the explosion of buying and displaying art in the Gulf States said recently, ‘When you’re aware of the politics, human right violations, gender inequality, and injustices that still exist, it makes you wonder if they’re trying to use these initiatives to conceal actual urban realities by portraying themselves as “progressive” and “cultural”.’ Tough words may be, but art – perhaps especially portraiture – has always been a highly contentious societal exercise. As Khaybullina’s portrait of President Putin illustrates, it is a conversation – sometimes a very difficult one – between the artist and the object of her art. The reality a sitter sees and inhabits, personifies even, like the story of a nation’s tragedies and triumphs, can be hard for the artist to capture and the subject to negotiate. Such is art.

The history of the evolution of portraiture is tortuous and cannot detain us long. From its earliest idealized Egyptian forms and more realistic Roman sculptures, portraiture of every kind was torn between demands for physical likeness and expectations of deeper meaning. As the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 BCE) is often quoted as saying, ‘The aim of Art is to present not the outward appearance of things, but their inner significance; for this, not the external manner and detail, constitutes true reality.’ Though portraits persist on tombs, coins, frescos and panel painting from Greco-Roman antiquity to the 14th century, we then begin to see royal portraits and minatures of individuals in illuminated manuscripts, which prepare the way for the flowering of portraiture in the Renaissance and thereafter. Wealth and power are the key drivers. Verisimilitude is to be matched by spirit and meaning: a fine face must convey a good heart and the subject’s strength of purpose; or, as in German artist and theoretician Albrecht Dürer’s (1471-1528) series of self-portraits, embrace a physical body and express an immortal soul.

Light and setting also begin to matter more. The art of portraiture becomes a science. Here’s the polymath Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) on the importance of position for a portrait:

A very high degree of grace in the light and shadow is added to the faces of those who sit in the doorways of rooms that are dark, where the eyes of the observer see the shadowed part of the face obscured by the shadows of the room, and see the lighted part of the face with the greater brilliance which the air gives it. Through this increase in the shadows and the lights, the face is given greater relief.

It is all very controlled and deliberate. Nothing is to be left to chance. In the 17th and 18th centuries portraits were to capture and convey position and status, heredity and family, community and vision. In the hands of masters like Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788) and Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792), clothing and landscape, irony and beauty, elegance and wit, are lifted to new levels of sophistication. As Reynolds said of his approach to a portrait, ‘[T]he grace, and, we may add, the likeness, consists more in taking the general air, than in observing the exact similitude of every feature.’ And so the history of portraiture evolved, at every stage, in the hands of experts, portraits of nations captured in portraits of people. For here class and values, pride and ambition, culture and religion, are laid bare for all to see, admire, judge and, for some, seek to emulate. No wonder portraits are so contentious!

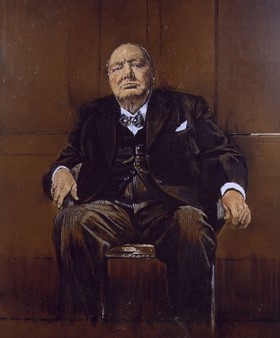

One of the most notorious – and tragic – instances of a portrait being rejected by its subject is that of war-time British Prime Minister Winston Churchill (1874-1965; PM. 1940-1945, 1951-1955) by the eminent modernist artist, Graham Sutherland (1903-1980), who had already painted leading contemporaries such as playwright W. Somerset Maughan (1874-1965) and newspaper mogul Lord Beaverbrook (1879-1964). The work, commissioned by the two Houses of Parliament in 1954 for 1000 guineas (ca. £32,000 today), has the elderly Churchill seated and scowling in a pose even his wife Lady Spencer-Churchill admitted was ‘really quite alarmingly like him’. The painting was unveiled, after a series of tense sittings, before both Houses in Westminster Hall on Churchill’s 80th birthday (30 November 1954). Sutherland sought to reflect Churchill’s words, ‘I am a rock’. Though on the day Churchill described it allusively as ‘a remarkable example of modern art’, in private he said it made him,’look like a down-and-out drunk who has been picked out of the gutter in the Strand’. He told Sutherland the painting ‘however masterly in execution’ was ‘not suitable’. In time, the painting shared the fate of other portraits by well-known – notably, Walter Sickert (1860-1942) and Paul Maze (1887-1979) – that the Churchill’s took exception to. In time, Sutherland’s work was consigned to the flames at Chartwell, their country home, on Lady Churchill’s instructions by their long serving private secretary Grace Hamblin (1908-2002) and her brother. When the news of the painting’s destruction emerged, Sutherland decried is as ‘an act of vandalism’. But the work had always divided opinion. Lord Hailsham (1907-2001) Churchill’s Conservative Party colleague and friend called it ‘disgusting’: Aneurin (Nie) Bevan (1897-1960), the fiery Welsh Deputy Leader of the Labour Party, praised it as ‘a beautiful work’. Beauty and ugliness are, it seems, in the eye of the political beholder!

As portrait painters go, Sutherland was a tough operator. Freed from residual Renaissance expectation that a famous or ambitious person would be depicted in a flattering light, he presented his subjects honestly, if not, to some, with cruel candour. Critics of Churchill’s response to the Sutherland portrait might say he was unwilling to admit the truth about himself the picture captured: that he was by then old and grumpy, a misshapen shadow of his former dynamic self. He might have once taken a bulldog bite out of Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) but no more. Such is ageing, and such is the harsh truth we see in a careless selfie or unposed snapshot by a friend. We are and are not who we think we are. And, of course, Sutherland captured something else, just as important, in his portrait of Churchill, a tired empire and worn out, post-War nation. In the leader you find and make a people.

There are many ways to depict a ‘Portrait of a Nation’. Economists and demographers give us graphs and statistics. Media magnates and trend setters tout their fashions and our foibles. Those who educate chart curricula developments to shape future generations. Those who aspire to lead cast their vision of the past, present and future. In some we see a true image and likeness, in others dishonesty and concealment, huff and puff, blandishment and blag.

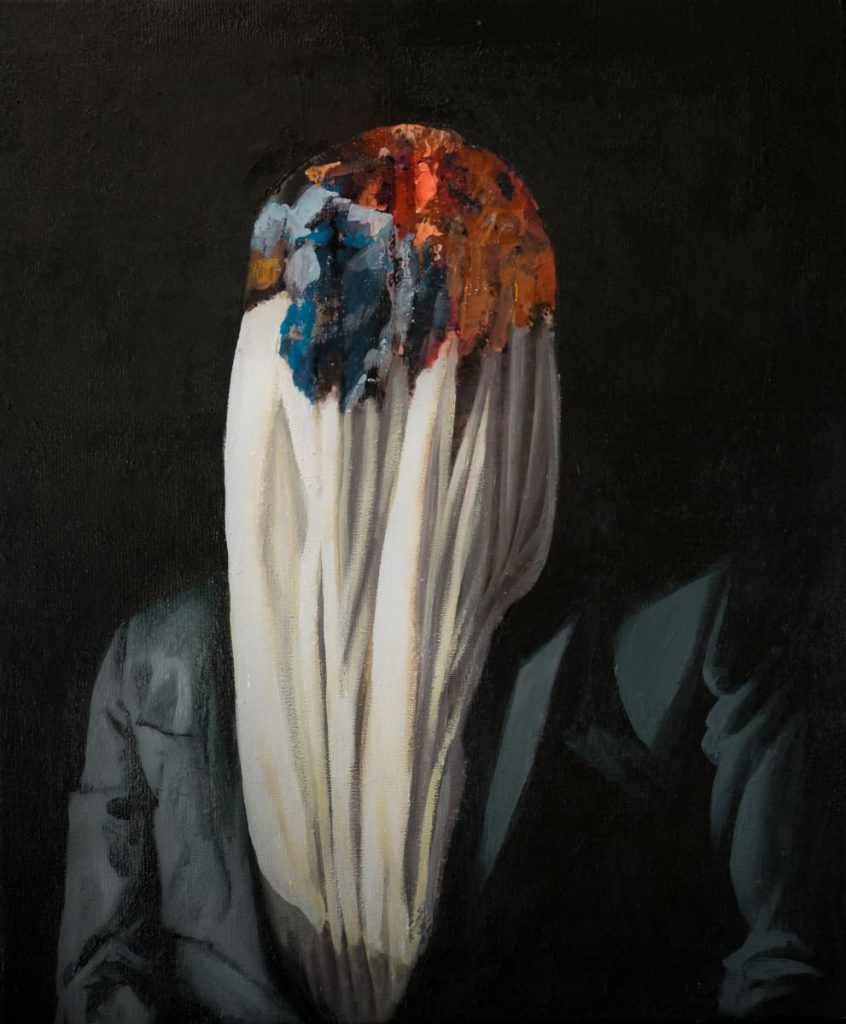

The Brussels-based contemporary Romanian artist Dan Laurentiu Arcus (b. 1983) is a student of society and of the human psyche, seeking, as he puts it, ‘to achieve an emotional response where different mediums are manipulated with a variety of tools’. Hence, he says of his painting The beloved citizen (2016), that the subject has ‘a veil completely covering his face, cancelling his sight and reducing his voice’. Adding rhetorically, ‘Isn’t this true for the perfect citizen for so many governing structures?’ In other words, discussion of national portraiture should be turned on its head. We should be asking, not what do we make of our leaders, but what do they make of us? Leaders are really only as good and bad as we make them. When they take us for a ride, or treat us as stupid, we are the real fools not them.

I find myself drawn more and more to the wisdom of Proverbs. Specifically, when I think of national life and international health, to the bald statement, ‘Where there is no vision, the people perish’ (29.18). Artists are visionaries, portrait painters especially so. They see what we miss. They open vistas onto landscapes where personalities are formed and lives lived. The problem is we don’t always want to see what they see. So, like Churchill, we turn away from our portrait. We deny the truth of Khaybullina’s irony. We find Sutherland’s approach too honest. But a good ‘Portrait of a Nation’ will be honest and deep. It will not only capture a nation’s soul in suffering by a bedside: it will lift its spirit by examples that inspire. It will also call out those who profiteer by ‘an eye for an eye’ and bite and tear to get their way.

Christopher Hancock, Director