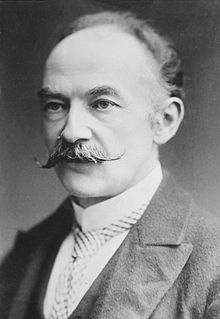

The ribbon village of Maiden Newton lies comfortably along a soft valley six miles north of the county town of Dorset, Dorchester, which local author Thomas Hardy (1840-1928) famously re-cast in his realist, romantic novels as the dark but alluring Casterbridge. If you take a back lane east from Maiden Newton, you plunge through an ancient ford in the road (near the delightfully named Sydling St. Nicholas) and, after a series humps and bumps, descend for a mile or so into equally delightful Cerne Abbas, nestling in a bowl of unspoiled English beauty – overseen by its famously graphic ancient giant (www.nationaltrust.org.uk/cerne-giant) carved into the chalky hillside. It is a part of the country my family know well.

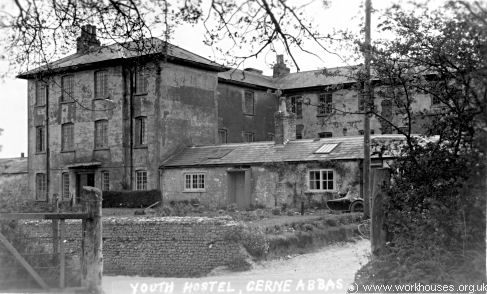

I hadn’t noticed until I took this backroad again yesterday – on a particularly beautiful Spring morning – how the last part of the journey is scarred by an ugly reminder of the (often) brutal face of Victorian philanthropy. On the western edge of Cerne Abbas stands its imposing 19th century workhouse, the Cerne Union Workhouse, built between 1836-7 as a refuge for the destitute from twenty neighbouring parishes. Now an attractive Care Home for the elderly, this once rambling pile was – as Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urberville’s (1891) tragically illustrates – the last hope for lives traumatised by scandal, sickness, suffering, unemployment and starvation. But, like other workhouses, care here came at a terrible price: shame, abuse, chronic illness, and death. Amid such beauty a terrible reality. Self-harm engraved on the soul of Victorian society, where love like life had a cruel face and pain was ‘transferred’ from one to another. The paradox of pain in beauty remains today.

According to a Mayo Clinic overview, self-harming, or ‘non-suicidal self-injury’, is ‘the act of deliberately harming your own body, such as cutting or burning yourself … [as] a harmful way to cope with emotional pain, intense anger and frustration’. Although precise statistics on self-harming are hard to glean – with an estimated 50% of cases remaining for various reasons unreported – the trend is clear, and troubling: many in supposedly happy homes and thriving countries out of need and/or choice harm themselves today. How very, very, sad.

To experts, the COVID pandemic has caused another wildfire: self-harming. In June 2019, citing a Lancet Psychiatry study, the BBC reported: ‘Alarming rise in self-harm – but only half get care.’ A Royal College of Psychiatrists report a year later (July 2020) had a section ‘Self-harm and suicide in adults’, which recorded 55,542 incidents of self-harming in the UK in the 12 months to December 2020. The Guardian newspaper likewise carried an article on 16 February 2021, ‘Self harm among young children in UK doubles in six years’, with 508 children aged 9-12 self-harming in 2019-20 against a figure of 221 in 2013-14. Psychiatry Professor Keith Hawton of Oxford University is quoted: ‘I do think it’s important that it’s recognised that self-harm can occur in relatively young children … it indicates that mental health issues are increasing in this very young age range.’ This sad problem is growing.

Mental health is a live issue in many societies: the pandemic seems to have stimulated self-harming. Writing in Forbes magazine (3 March 2021), American journalist Tommy Beer says insurance claims for self-harm among teenagers in the US have ‘increased 99% during [the] pandemic’. That is, between April 2019 and April 2020 insurance claims for help with self-harming in the 13-18 age group increased 99.8%; and, according to a Fair Health study, between August 2019 and August 2020 in NE America the increase was a shocking 333.9%. This is not just a Western problem. Writing, again in medical journal The Lancet (December 2020), mainland Chinese medics Pei Zhang, Ning Zhang and Chun Wang contrast the 19.5% of children and adolescents worldwide who self-harm with the 27.4% who do so in China. COVID, it seems, is not the only pandemic the world is facing. Self-harming is endemic in many modern societies; indeed, societies are themselves self-harming agents, it sometimes seems, when they knowingly inflict pain on the body politic. We will come back to this later.

Let us pause for a moment to focus on the character and causes of self-harming. These are complex matters, the literature around them vast and growing. A number of features and factors stand out. As we have seen in the Mayo Clinic overview, most commentators see non-suicidal acts of self-harm as a way of turning (most often) inarticulate, invisible, painful thoughts and feelings into tangible, physical, and privately visible, realities. Pain finds form, reliability, and temporary release or relief. In distress, pain is overcome by pain; a sense of self-loathing exchanged for a need for self-care; the anguish, numbness and dissociation of acute feelings displaced by a perverted sense of being in control. But respite is evanescent.

The aim of self-harming is not suicide, but identity exchange and a recovery of self-worth. It is not surprising an estimated 17% of people will self-harm during their lifetime, such is the pressure many have felt – and feel – when teased, mocked, isolated, changing or aging. That a suggested 25% of teen-agers self-harm is equally tragic, but probably unsurprising, with the average age of the first act 13 and incidents thereafter linked (according to one UK survey) with disorders of personality (20%), adjustment (13.5%), mood (viz. bi-polarity, 11%), eating (55%) and various degrees of excoriation (skin picking) and trichotillomania (hair pulling). According to Mental Health America, the most common forms of self-harm are skin-cutting or piercing (70-90%), head banging or hitting (21-44%), and burning with a flame or constant act of rubbing one area (15-35%). One set of statistics indicates that of those who self-harm 5% are adults, 17% teenagers, 15% university or college students, 35% male and 65% female (with gays and bi-sexuals at particular risk). As noted already, only 50% seek help, and that often from a trusted (or also self-harming) friend. The pain is clear: the need to invest in understanding and addressing the problem equally so.

Lest we perpetuate denial or evasion of the problem, a few more specific points on the what and why of self-harming. First, as a private, often inarticulate, coping mechanism, signs of self-harm need to be read carefully and skilfully: patterns (and symbols) in scars (esp. to the front of the body and arms), fresh wounds of different kinds (incl. scratching and inserting objects under the skin), excessive rubbing of one area to create a burning weal, a penchant for sharp objects, wearing long sleeves or trousers even in hot weather, frequent appeals to ‘accidental injuries’, and then the full range of personal, emotional and verbal semiotics, from difficult domestic and social relationships to volatile behaviour, to voiced self-loathing and despair. The signs are often there, we are told, if we will read them.

But why? Here’s one teenage self-harmer: ‘I didn’t know how else to cope. I didn’t like myself’. And another, quoted by the UK mental health agency Mind: ‘I think one of my biggest barriers to getting help was actually not admitting to myself that I had a problem. I used to tell myself, “I’m only scratching, it’s not really self-harm”.’ Yes, self-harm may be an expression of poor coping skills (esp. with psychological pain) and of difficulty managing emotions (esp. dealing with worthlessness, loneliness, panic, anger, guilt, rejection, self-hatred, or confused sexuality), and be expressed in different ways and variously linked to risk, shame, a sense of failure, guilt, or anxiety (incl. academic or sexual pressures) and a little, passing, relief; but, like an addiction, its power can spread. Copy-cat behaviour and drug-induced experimentation increase the risk – and the likelihood – the problem/s will persist. But help is at hand, of course, when, or if, the issue is named and need admitted.

While study of individuals who self-harm grows, there is little if any acknowledgement that modern societies are themselves self-harming agents. Victorian society was not unique in venting suppressed feelings on its citizens, in ‘transferring’ inherited pain from abusive fathers to vulnerable daughters, from a vicious judge to an innocent victim, from classist elites to a hapless under-class, and, perhaps most shamefully, from a self-righteous church to a ‘sinful’ world. In the name of its perception of ‘good’, Victorian society perpetrated all manner of ‘evil’. Few question that interpretation nowadays. But too few are, I would argue, ready to admit that the transference of pain is also a modern societal problem, that modern ‘goods’ do untold damage and modern life inflicts pain in the name of ‘love’. And let us be clear: it’s not just cultures that harm citizens: both, as cause and consequence of pain, self-harm. So, a culture of self-harming is created and destructively perpetuated, with modern societies (like most self-harmers) in denial of their abuse or defensive of their perception.

Let me end with three examples of ‘self-harming societies’. You may think of others: here are mine. First, few students of China question the damage the first ‘Cultural Revolution’ (1966-1976) did to the fabric of Chinese society, its families, communities, psychology and self-esteem. Data on mental health and marital strife, domestic abuse and infanticide, have time and again reinforced the psychiatric truism that systemic dysfunction plays itself out in the minds and lives of individuals. The ideological and physical scarring of the ‘Cultural Revolution’ is seen in many of China’s elderly citizens, from whom a majority of its present leadership is drawn. So how has China coped with this societal pain? By renewing it in the ‘Second Cultural Revolution’ currently underway; a revolution in which pain is ‘transferred’ from abused leaders to countless, powerless individuals, whose lives become the ‘whipping boy’ of unresolved Chinese aggression. China’s predisposition to self-harm is engrained in its culture: like an isolated, self-harming individual, it wilfully hurts itself because it feels underappreciated and unloved by the rest of the human family. International Relations is alert today to the centrality of psychology to modern diplomacy. ‘Self-harming’ fits the profile of totalitarian regimes that wilfully hurt and violently suppress dissenting opinions. The new ‘workhouses’ of brothels and drug factories, re-education camps and state-imposed school curricula, where lives are brutalised and minds terrified, are as abominable as Victorian equivalents. Amid the ‘beauty’ of China’s ‘super-power’ status lurks the ugly truth of the price paid by its citizens to attain and maintain that profile. Self-harming societies inflict pain on themselves and on the world to help them cope with their own. Such is the power of pain.

Second, closer to home, what of Western cultures that worry at problems like the rubbing or burning of a patch of skin by a troubled self-harmer? What impact do our repeated calls for ‘reparation’ or ‘rights’ have on the mind and heart of our cultures? What harm ‘resentment’ and ‘unresolved conflict’ on societies that accept or teach them? In the name of modern ‘good’ they inflict, I suggest, incalculable harm on the body politic by penetrating the fabric of societal trust and by opening and re-opening the wounds of relational failure. A weal forms on society’s skin when it is fixated on issues and historic hurt. To take the discussion back a stage, when incidents of individual self-harm (and other forms of emotional disorder) are in the ascendant, we know pain and strain are present. If we see their impact on China, we should admit their power in the West. To claim Western societies are free of cultural abuse is disingenuous if statistics show an increase in self-harming. But to be clear: this is not to deny the need (at times) for ‘reparation’ and the legitimacy of (some) appeals to ‘rights’, it is to cross-examine their motivation to ensure that, as in Victorian Britain, the abused are never again allowed to become abusers or agents of pain ‘transference’ where others are ‘made to suffer’. As with private incidents, societal self-harming is a complex phenomenon. Psychoanalytic ‘systems theory’ and the socio-anthropological study of ‘group behaviour’ are, like the ‘affective dimension’ in modern International Relations, tools to break the cycle of inherited abuse and name the ‘powers’ that claim to shape who or what we are. Freedom, peace, fulfilment, and self-harming do not, and cannot, coexist. Protesters take note.

Last, ‘self-harming societies’ are to my mind in evidence when communities consciously or unconsciously permit practices that promote individual self-harming. That is, when there is no expectation that advertisers will work to mitigate factors inspiring a self-harmer’s sense of being unattractive (and thus worthless), or that busy, professional parents are justified in nurturing love-poor offspring, who are left to find their way with a credit card and new mobile phone. ‘Self-harming societies’ come in many forms. Their progeny is similar: pain-filled, desperate orphans who turn to self-inflicted injuries as a mechanism to remind themselves they exist. A society harms itself when it allows this to happen to its own. No wonder, perhaps, many have found comfort in the Judeo-Christian vision of a vicarious ‘suffering servant’ ‘by whose wounds we are healed’ (Isaiah 53.5). For, here true beauty and peace are found amid unimaginable pain.

Christopher Hancock, Director