On the day Iran goes to the polls (June 28) and Democrat America recovers from last night’s presidential debate, we are reminded in two contrasting ways that 2024 is a year of elections, albeit staged, planned, reported and recorded in a host of different ways.

The National Democratic Institute in Washington DC[1] lists 64 national elections[2] (and numerous local elections)[3] taking place in 2024. With 8 of the 10 most populous countries voting[4] – in addition to elections for a new National Assembly in South Africa in May and the European Parliament in June, and the snap elections in July called by UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak (b. 1980; PM 2022-present) and French President Emmanuel Macron (b. 1977; Pres. 2017-present) – a quarter of the world (ca. 2bn) is eligible to vote in 2024, with at least half of the world’s population directly (and millions more indirectly) impacted by the results. This is not only an extraordinary coincidence (and source of immense interest to psephologists world-wide!), it is also a good reason to stand back and consider the fact and state of electoral processes globally. Some of these elections this year are timed by tradition or the end of a term in office, others are a consequence of national politics, opportunism or death, but voting there is on a mega scale.

The effect of all these elections is 2024 has been, and will be to its end, dominated in a unique – if not extreme – way by political commentary, geopolitical wariness, media speculation, societal unrest and a deal of predictable nervousness in the global financial markets. Cynics and sceptics may wonder, ‘Will it make any difference?’ The thoughtful and concerned will ask, ‘Can it make a difference?’ In the end, time, and the actions of electors and elected, will tell. As the Chicago-based journalist Sydney J. Harris (1917-1986) quipped, ‘Democracy is the only system that persists in asking the powers that be whether they are the powers that ought to be.’

My theme in this Briefing is the lessons this year’s elections, and elections per se, can and should teach leaders and led in 2024; indeed, in any year and any place elections are called. I write in light of Oxford House’s vocation to ensure culture, ethics and religion/spirituality are integrated in geopolitical analysis and international diplomacy. Viewed through this vital interpretative lens, the fact, character, and consequence of elections acquire new weight, urgency and definition.

To some, the multiplicity of elections in 2024 is unequivocally good news. Elections are to them a sign of mature government and politically engaged people. Campaigning and arguing, billeting and badgering, manifestos and hustings, are to devotees of elections vital signs of a democratic body that is both alive and well. To others, elections rarely live up to the claims made for them. Candidates disappoint. Promises are broken. Majorities are slim and mandates weak. Claims of ‘change’ vain and vacuous. Hence, our sceptic asks, ‘Will it make a difference?’ and our earnest elector wonders, ‘Can it make a difference?’ More pointedly, both might now question the over-confident politico whether voting per se – even in (hitherto) robust democracies and well-ordered countries – isn’t subject now to such intentional and unintentional pressure from powerbrokers and pundits, pollsters and party machines, political intrigue, finance and foreign interference, that an open, honest, ballot-box isn’t now a strategic risk no aspirant or ambitious leader would consider or silly ‘right’ no serious political mobster would permit. For, ‘free and fair’ elections aren’t just a dream in dictatorships, they are an increasingly distant memory in many erstwhile democracies. ‘So, what’s new?’ you might ask. Certainly, no Englishman could ever claim our oft-praised form of ‘parliamentary democracy’ hasn’t over the centuries been subject to monarchical pressure, populist coercion, elitist presumption, electoral waywardness, and today (perhaps to an unparalleled degree) to a pervasive sense of disenfranchisement and dismay among electors young and old.[5]

2024 may be a year of elections, but of what value is that if in theory and reality elections count for so little and are subject to carefully deployed forces (of every kind) that aim to determine, if not to discredit, a voter’s decision? In what follows, I make three rather obvious points in reply to that question and then four hopefully(!) more nuanced ones. The bottom line is, surely, that the right to elect matters; indeed, matters enough to defend that right when and where and however it is threatened. As Aristotle (384-322 BCE) wrote, ‘No democracy can exist unless each of its citizens is as capable of outrage at injustice to another as he is of outrage at injustice to himself.’

So, to my three rather obvious points.

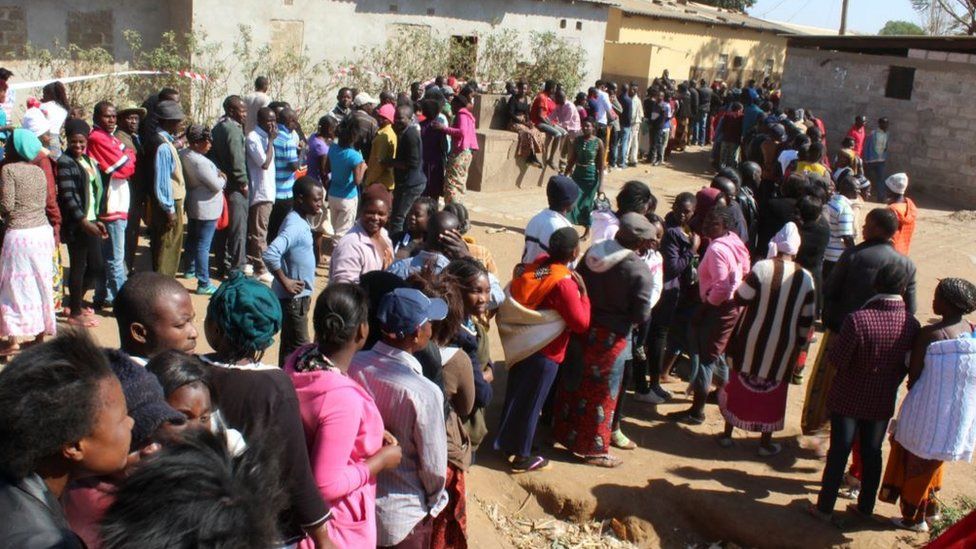

First, the privilege and responsibility of voting. The right of every individual to freely express their view on who should govern, and to demonstrate that in a discrete election, is not enshrined in the law or constitution of every country. Where it is, it should never be taken for granted. As President John F. Kennedy’s (1917-1963; Pres. 1961-1963) younger brother, the assassinated Democrat politician Robert (‘Bobby’) Kennedy (1925-1968) said, ‘Elections remind us not only of the rights but of the responsibilities of citizenship in a democracy.’ How moving it is to see long queues for polling stations in countries where citizens remember that voting is a hard-fought privilege and a precious, but vulnerable, gift.[6]

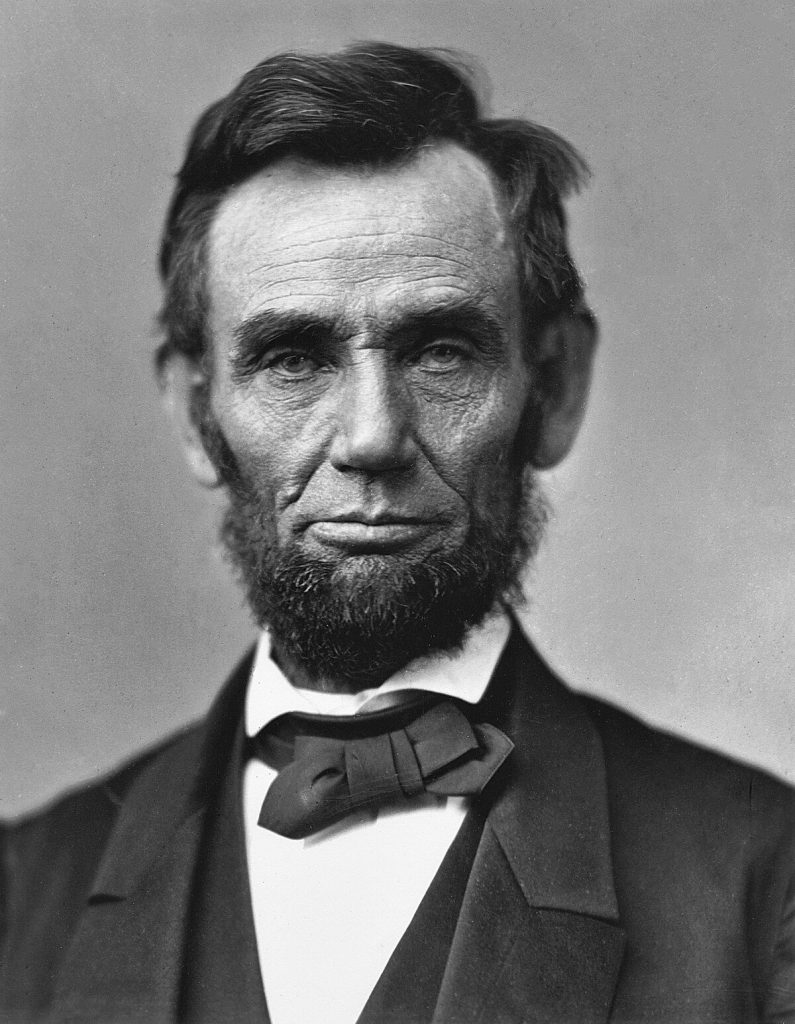

How sad, then, when citizens fail to exercise their democratic right. As the American columnist Bill Vaughan (1915-1977) memorably complained, ‘A citizen of America will cross the ocean to fight for democracy but won’t cross the street to vote in a national election.’ Or, as the astute polymath politician and Founding Father of the United States of America, Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826; Pres. 1801-1809) pointed out, ‘We do not have government by the majority. We have government by the majority who participate.’ Spoiled ballot papers, like electors who don’t cast their vote, play into the hands of those who want power for power’s sake and disrespect the electorate. The Classical Greek philosopher and political theorist Plato (ca.427–348 BCE) was surely right, ‘One of the penalties for refusing to participate in politics is that you end up being governed by your inferiors.’ Statistics indicate that voter numbers have declined globally since the 1960s; although high turnouts do not always indicate an election is ‘free and fair’ or that a system of government is robust.[7] Be that as it may, one thing is clear, in a year of elections if you are eligible to vote … VOTE! Or at least remember that other assassinated US President Abraham Lincoln’s (1809-1865; Pres. 1961-1965) caustic warning, ‘Elections belong to the people. It’s their decision. If they decide to turn their back on the fire and burn their behinds, then they will just have to sit on their blisters’!

Second, the possibility and reality of electoral fraud and coercion. Though voting is an immense privilege, it is also (necessarily and inevitably) an imperfect form of government. Why so? First, because all of us, be we voters or candidates, are flawed, fallible, creatures. Thankfully, our right to vote is not based on our soundness of judgment or morality! As Plato saw, ‘Democracy… is a charming form of government, full of variety and disorder; and dispensing a sort of equality to equals and unequals alike.’ Second, because democracy, and the process of elections on which it is based, are susceptible to corruption, be it through vote-rigging, voter intimidation, bribery or cyber-attack.

Let’s be clear, there is all the difference in the world between our inevitable human fallibility and an intentional desire, seen (it seems increasingly) among political gangsters and world leaders, to pervert the course of justice and pre-determine the outcome of an election. Democracy may be a flawed ideal, but to exploit those flaws for profit, power or other kinds of self-interest, only serves to undermine claims for what war-time British statesman Winston Churchill (1874-1965; PM 1940-1945, 1951-1955) – and others before and since – have seen to be ‘the worst form of Government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time … in this world of sin and woe’. But – and this contributes to disenfranchisement among younger voters – electoral fraud and coercion exist today on an industrial scale. Sophisticated processes to enable and detect electoral fraud serve to increase societal (and political) awareness of the problems and possibilities surrounding this issue. The net result is heightened awareness of the risks for some and value for others of social (and thus global) volatility. Reflecting sensitivity to this, the South African Police Chief Bheki Cele cautioned members of former President Jacob Zuma’s (b. 1942; Pres. 2009-2018) defeated MK party after the June 2024 elections, the authorities would, he said, not tolerate ‘threats of instability in order to register objections or concerns about the electoral processes’. Challenging electoral results and/or accusing rivals of corrupt practices are, for many observers, but nails in the coffin/s of Western democracy and global political integrity.

Third, the predictability and unpredictability of elections. Though pollsters, party leaders, and dictators may try to predict, or control, the result of an election, freedom, choice and chance still have a role to play. Sickness, the weather, local pressure, last-minute crises and a host of other variables, can never be ruled out. Unpredictability is written into the long history of elections and electioneering:[8] it’s what makes a year full of elections rich in possibilities for punters and a juicy morsel for journalists! As we have seen already, removing risk from the result has become almost as important to leaders in mature democracies as to tyrannical rulers of autocracies. In both instances, the predictability of an election result is at a premium.

At a deeper level, as we will see shortly, the predictability of an election lies not only in there being a result (however it is achieved) but that there will be ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ regardless of a victor’s popularity. The finite nature of an electoral process draws a line in a nation’s history to which reference can subsequently be made to bolster position or justify dissent. The predictable unpredictability of elections is offset by the certainty of a result, even when contested. As such, elections bring form and focus to the otherwise fluid state of a nation’s political identity. Here freedom or repression, opposition and opportunity, are brought into sharp relief in a country’s culture and self-understanding. If a democratically elected leader can take pride in his or her new electoral mandate, the autocrat must mask and deny the mirror and spotlight a rigged election are on his or her willful oppression. As the Czech-born British playwright and screenwriter Sir Tom Stoppard (b. 1937) wisely noted, ‘It’s not the voting that’s democracy; it’s the counting.’ After all, every vote matters to someone!

Now to my four hopefully more nuanced points on lessons to be learned from elections.

First, the power and presence of the ‘tribe’. As political theorists and analysts are acutely aware, the democratic ideal of ‘one person, one vote’ struggles to counter the grass-roots reality of the power of a ‘tribe’; be they literally an ethnically defined tribal community (as in many parts of the world) or a socially or culturally identifiable looser affiliation of the like-minded.[9] In either case, the concept of a ‘free and impartial’ vote is a myth. Electors follow more than lead. They listen to prevailing opinions and look over their shoulder when they post their ballot paper. So, regardless of specifics of personality or policy, electoral choices are effectively predetermined by what the mullah at the local mosque teaches, the influencer sells, or the media mogul desires.[10] Democracy is far less clearly defined, and in many places less desirable, where tribe trumps private judgment.

Tribalism is the cousin of populism and the illegitimate grandchild of a person’s unique identity. Though corporatism is much (too often?) scorned where subjectivism and individualism reign, it is as potent an electoral force as ‘I have a right to vote and express my political opinion’. If you doubt the power of ‘tribe’ in a democracy, ask yourself how many parents in the UK will urge their first-time voting offspring to vote according to their conscience, or how many Republican parents will be accepting of their child’s choice of Biden (or his replacement?). Equally, I wonder how many churches in India or South Africa, Russia or Indonesia, put spoken or unspoken pressure on congregants during the countries’ recent elections to accept or reject the ruling power. In a year of elections, we would do well to remind ourselves to vote and to think before we do so. As US President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945; Pres. 1933-1945) wisely pointed out, ‘Democracy cannot succeed unless those who express their choice are prepared to choose wisely. The real safeguard of democracy, therefore, is education.’ How very true…

Second, the pervasiveness of corruption. We name the power of ‘tribe’ not because it is always wrong, but because it can be. We name corruption because it is always wrong and ever present. Though we may squirm at Churchill’s condescension (‘The best argument against democracy is a five-minute conversation with the average voter’) and cynicism of the journalist H. L. Mencken (1880-1956) (‘Democracy is a pathetic belief in the collective wisdom of individual ignorance’) and pessimism of the naturalist philosopher and poet Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) (‘There is but little virtue in the action of masses of men’), the simple fact is imperfect people vote for imperfect reasons for imperfect people. Such corruption is endemic to the human condition. However, as we have begun to see above, the universal predisposition to err is exacerbated when various kinds of electioneering engage in willful perversion of votes, voting and electoral results. Transparency International identifies three common types of corruption, viz. vote-buying (when a politician or party seeks to secure support through promising ‘access to public services or preferential treatment’), the abuse of state resources (i.e. using the public purse, media or personnel in an election campaign, or changing laws for political benefit) and election rigging (via misinformation, mis-recording of votes, ballot-stuffing and manipulating voter registration, credentials and constituency boundaries).[11] If not already included, bribery, cash for honours, patronage, nepotism, cronyism, embezzlement, kick-backs, ‘Gombeenism’ (acting for personal financial gain), fraud, the threat or fear of ostracism or exposure, and the privileging of ‘parish pump’ politics (local issues) over national interest, all undermine a level electoral playing field.

The acceptability of electoral corruption is linked to societal norms.[12] Though unintelligible to many inside and outside India and Russia, votes for Prime Minister Narendra Modi (b. 1950; PM 2014-present) or President Vladimir Putin (b. 1952; Pres. 1999-2000, 2000-2008, 2012-present) in this year’s elections enabled regimes to continue because legitimacy couldn’t be questioned, or integrity challenged. The message was clear – and heeded by many – ‘Opponents beware!’ Seen in this light, ‘corruption’ isn’t so much a set of actions as a culture of pressured loyalty and uncritical acceptance. Reducing corruption to money denies the complexity of intimidation and seductive power of conformity. People of faith might remind themselves in this year of elections, not only to vote and think beforehand but to pray before and after doing so: they are accountable to a higher power. Not that prayer expunges imperfection, but it can help mitigate its impacts!

Third, the myth of power. Elections are predicated on the right and possibility of an individual or party securing, or preserving, their hold on power; power, that is, purportedly to govern a city, state, school board, or country, and to make decisions that shape a community or nation’s life. Ideally, this power is dispensed for the ‘common good’ and rejected when abused. The fact is, of course, an elected position often affords less power and satisfaction than the ambition behind it, while personal fulfilment and policies frequently fail under institutional inertia and frustration. As such, elections contribute to exposing the partial and provisional nature of earthly power. A ‘term in office’ comes to an end. A vote of ‘no confidence’ brings down a government or Prime Minister. Complacency erodes a working majority. Rivalry undermines the boss. A coup erupts. Tyrants are thrown to the dogs. The unpleasant face of human power politics is plain to see.

Elections not only expose the myth of power, they also disabuse elected officials of the foolish notion their exercise of power is necessary and permanent. In the words of poet Robert Bridges (1844-1930) ‘tower and temple fall to dust’. Hubris has a way of humbling those who worship her and, like domestic conflict, it can all get very messy. The net result? – an increasing sense that the whole wretched business of government achieves very little and does me and mine little good. Not surprisingly, we hear more often, ‘I choose not to vote.’

To people of faith, elections are always a good and timely reminder of the essentially contingent nature of all temporal authority and all human judgment. To claim more, given what we have seen and said already, is to live in an odd, artificial world in which human institutions are held to last for ever and position never passes its ‘sell-buy’ date. Rubbish! Like a storm that clears the air, elections wash the world so we can see in renewed ways the good leaders can do and the folly of those who claim all power is truly theirs.

Lastly, the persistence of opposition. Like religious persecution, political victories are almost always the seedbed of courageous opposition. They sharpen and inspire vision in those who dissent. Hollow electoral victory haunts the would-be immortal – but thus deeply immoral – political autocrat. How different that from the wholesome checks and balances of government and opposition in a healthy democracy.

There are two other points to make under this heading as I end.

First, ‘opposition’ is by name and nature adversarial. Elections feed off controversy and disagreement; indeed, they stockpile the combustible material of a mature society … dialogue. Yes, electioneering can be rancorous, rude and divisive, but better that, I would argue, than the sickening silence of begrudging consent or stifled freedom of speech. What is very troubling, of course, is when supposedly mature Western democracies make speaking freely as hard as it is in crude oppressive regimes. No, opposition is good: it reminds parties and leaders they may be wrong and their willing opponents that they have a civic duty to make their counter case clear.

Second, opposition persists because people will to disagree. I don’t just mean there will always be some who choose to be contrary. I mean the ‘will of the people’, on which good government depends, should never be conceived as univocal. People can and will disagree, there is nothing wrong with that – indeed, without the energy opposition creates the ‘will of the people’ is apt to become a flaccid, lifeless thing. The deep tragedy of a pervasive sense of disenfranchisement is it denies candidates and voters the chance to hammer out ideas on the anvil of resistance. So, in a year of elections, the call should be not only ‘Vote, think, pray’, but ‘Be sure to disagree!’ As the Wall Street journalist Peggy Noonan rightly argued, ‘Our political leaders will know our priorities only if we tell them, again and again, and if those priorities begin to show up in the polls.’

Professor Christopher Hancock – Director

As in all Oxford House Briefings, every effort is made to attribute images where information is available.

[1] NB. The NDI is funded by an international consortium of countries.

[2] For a list, see the National Electoral Calendar: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2024_national_electoral_calendar; accessed 21 June 2024.

[3] For a full list see the Local Electoral Calendar 2024: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2024_local_electoral_calendar; accessed 21 June 2024.

[4] Cf. Bangladesh, Brazil, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Pakistan, Russia and the USA.

[5] There is some suggestion the 4 July General Election in the UK will see one of the lowest turnouts in history. According to the data, consulting and public affairs company Techne 30, 20% of the electorate has already decided not to vote, while 30% of 18 to 34 year olds aren’t even registered to vote: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/voter-general-election-low-turnout-b2559156.html; accessed 27 June 2024.

[6] In February 2024, blasts at the offices of candidates in Balochistan killed 17. In the same month, 114 poll workers died during the General Election in Indonesia. In June 2024, 33 poll workers died from extreme heat in a single day in Uttar Pradesh during the Indian elections (19 April to 1 June 2024).

[7] In the UK, the General Elections of 1950 and 1951 saw a turnout of more than 80%. By 2001 this figure had declined to 59.4%, marginally higher than the 57.2% in 1918. Though turnout has risen since 2001, it remains below the level of 1997 and the 71% average between 1922 and 1997. According to the World Population Review, the countries with the highest turnout for presidential elections in recent years were Equatorial Guinea 98.41% (2022), Rwanda 98.15% (2017), Turkmenistan 97.17% (2022), Singapore 93.55% (2023), Togo 92.28% (2020), Angola 90.37% (1992), Uruguay 90.12% (2019) and Gambia 89.34% (2021): those with the lowest turnout Haiti 18.11% (2016), Afghanistan 19% (2019), Nigeria 26.71% (2023), Mali 34.42% (2018), Bulgaria 34.64% (2021), Central African Republic 35.25% (2020), Kyrgyzstan 39.16% (2021), Portugal 39.26% (2021), Algeria 39.88% (2019) and DR Congo 41.05% (2023). However, as is often pointed out, a high turnout (as in Rwanda) may be linked to government pressure and a low turnout (as in Afghanistan) an expression of political protest. See further on this: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/voter-turnout-by-country; accessed 25 June 2024.

[8] For critical reappraisal of the predictive value ‘structural forecasting models’ see R. Nadeau, R. Dassonneville, M. S. Lewis-Beck. P. Mongrain, ‘Are election results more unpredictable? A forecasting test’, Political Science Research and Methods 8.4 (2020): 764-771: https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2019.24; accessed 26 June 2024.

[9] For commentary on ‘tribal’ voting in the UK, see e.g., https://www.telegraph.co.uk/politics/2024/06/05/six-voter-tribes-general-election-2024-middle-britons; accessed 27 June 2024; ‘Three-D Politics and the Seven Tribes’, Electoral Calculus: https://www.electoralcalculus.co.uk/pol3d_main.html; accessed 27 June 2024; https://inews.co.uk/news/politics/the-ten-tribes-who-will-decide-the-election-and-who-the-parties-need-to-unite-3094357; accessed 27 June 2024. On ethnic voting in Africa, see, e.g., D.N. Posner, ‘Ethnic Voting’, in Institutions and Ethnic Politics in Africa (Cambridge: CUP 2012), 217-250. Comparable analyses are available for the impact of religious orientation and affiliation on voting patterns world-wide. In the UK, no party leader can ignore the power of the local church, mosque, temple, gurdwara or other centre for worship. The impact of local mosques on voting in North Africa after the Arab Spring is another important instance of ‘tribal’ religioius politics.

[10] Hence, voters are now targeted by parties and candidates not as individuals but as members of a ‘tribal type’.

[11] Cf. on this: https://knowledgehub.transparency.org/guide/topic-guide-on-electoral-corruption/5189; accessed 26 June 2024.

[12] For an index of levels of corruption worldwide, see: https://worldjusticproject.org/rule-of-law-index/factors; accessed 26 June 2024.