For non-UK readers of Oxford House’s Weekly Briefings, on 15 October 2021 the 68-year-old British MP, Sir David Amess (1952-2021), was attacked with a knife in his constituency. Sir David died at the scene. On 21 October 2021, BBC News reported: ‘A 25-year-old man has been charged with the murder and with the preparation of terrorist acts after the fatal stabbing’. This is a personal tribute, and more general reflection on the incident, by one of Sir David’s former parliamentary colleagues, Jeremy Lefroy.

Before I begin, I would like to express my deep condolences to the family of Sir David Amess at this time of tragic loss and assure them of my profound sympathy and prayers.

I can’t think of anyone in Parliament who came close to Sir David Amess in speaking up for the concerns, dreams, organisations, businesses, and, most importantly, the people of his constituency. Sir David was Member of Parliament for Southend West from May 1997 until his assassination on 15 October 2021. He was previously MP for the ‘bell-weather’ parliamentary seat of Basildon in Essex from 1983, being famously re-elected in 1992. Boundary changes led to his being subsequently elected MP for Southend West, a position he held for twenty-four years. It was my honour, on several occasions, to speak in the regular debates, which Sir David tirelessly championed, at the end of each parliamentary ‘term’. Like many MPs, he found these debates, on the eve of the parliamentary recess, useful opportunities to raise issues relating to their constituency (and more generally), which they had not been able to raise before on the floor of the House of Commons.

The last time I sat with Sir David through one of these ‘end of term’ debates was 22 July 2019. I remember the occasion well. Parliamentary protocol allowed for six-minute interventions, so as many MPs as possible could speak. In the six minutes allocated to Sir David, he managed to raise with speed, skill, wit, and palpable humanity, no less than 32 issues! As usual, he put a smile on many members’ faces on both sides of the House. It was a characteristic parliamentary tour de force. The issues he raised included a broad range of local and national concern: among them (Hansard reminds me) were –

- The importance of fitting sprinklers in all high-rise buildings and dealing with faulty cladding, following the Grenfell Tower fire (14 June 2017)

- Obtaining city status for Southend-on-Sea (This was granted by HM The Queen on 18 October 2021, in honour of Sir David’s tireless campaigning)

- Two constituents who had paid their full National Insurance contributions for 47 years and somehow still did not qualify for a full pension

- The need for a Government Inquiry into avoidable epilepsy deaths and a funded annual risk check for people with epilepsy

- The number of people who were having visas turned down unjustifiably

- Compensation for those unjustly accused of child abuse by (the now discredited claimant) Carl Beech

- The need for additional Primary and Secondary school funding

- The educational inspectors’ Ofsted report that adjudged one Southend school ‘Excellent’ and singled out two staff members for particular praise

- Vehicle Excise Duty on mobile homes

- The 12,000 deaths a year of men from prostate cancer and a constituent who was campaigning on the issue

- Support for the National Council of Resistance of Iran

- A report on a visit to Albania to see the house of Mother Teresa (and questioning of the absence of a statue of the British comedian Norman Wisdom in a country where he was so popular!)

- Ending the debt trap

- Fumes from planes at Southend Airport that were adversely affecting constituents

If anyone wonders why Sir David’s murder was met with such an outpouring of grief in Southend and, indeed, across Britain, they have only to read his adjournment speeches: they are among 11,189 contributions recorded by Hansard over his 38-year career in Parliament. His words consistently display deep affection and concern for his area and, more importantly, for the people who lived there, who he represented gladly, regardless of their political beliefs or religious views. David himself had a deep, personal, Christian faith, and was active in his local Roman Catholic Church; indeed, it has not gone unnoticed that he was killed in a Methodist Church in Leigh-on-Sea during a regular ‘surgery’ for constituents.

Sir David contributed to the life of Parliament in many other ways. One of the necessary – but unglamorous – tasks an MP faces is to chair the committee stage of bills and debates that takes place in Parliament’s second chamber, next to the House of Commons, the ancient Westminster Hall. I was fortunate to have Sir David in the chair for the committee stage of the Private Members Bill I sponsored in 2014: in time, this became the Health and Social Care Safety and Quality Act 2015. Sir David’s opening remarks from the Chair were characteristic of the man and set the tone for what followed. He simply said: ‘I hope we will proceed with good order and the sitting will be a happy one.’ That was Sir David through and through: first, he believed in good order and courtesy in debate, and he wanted other people to be happy … which he almost invariably seemed to be.

Eulogies tend to present a favourable picture of the deceased; understandably so, when the loss is recent and family and loved ones are grieving. In the case of Sir David, the warm words expressed by so many in Parliament, Southend and the country at large, did not speak of part of the man – they described all of the man I came to know and respect over the nine and a half years we sat together in Parliament.

As commentary on Sir David’s death has already registered, it has become increasingly difficult to protect Members of Parliament and, indeed, other professionals who engage with the public face-to-face day-in-day out, such as medical staff and social workers, teachers and prison officers, police and (especially, it seems, during the pandemic) shopworkers. This is, perhaps, particularly – or, better, uniquely – difficult in relation to MPs, who hold regular open ‘surgeries’ when they make themselves available to meet their constituents and who are ‘on duty’ whenever they are in their constituency. When I was MP for Stafford (2010-2019), I was often stopped in a shop or on the street. Most people were very friendly, some let me have a piece of their mind! Like it or not, I was their elected representative in Parliament, and they had (and have) a right to express their views. In any given week, MPs attend public events where they are in the spotlight and, crucially, have no security. The risk is clear.

The UK’s system of representative democracy includes the historic expectation – indeed, obligation – that MPs be accessible to the public, and that constituents have first call on their time and attention. To enable the latter, across the country constituencies have been kept to a manageable size in terms of residents (ca.100,000) and electors (ca.70,000). This system has worked well since the extension of the franchise in the 19th and early 20th centuries. And, it has a number of wholesome consequences that can be overlooked:

First, that the UK has 650 MPs, a much larger number than in many countries with a similar size of population. The effect of this is that access to power reaches far and wide in local communities. This is good for democracy per se.

Second. that an MP has a duty to represent everyone in their constituency, including those who cannot (yet) vote or voted for someone else! This is vitally important. It is incumbent on an MP to listen to every constituent and provide whatever help and advice they can regardless of their social standing, party affiliation, or in expectation of their vote at the next General Election. Like many MPs, I confess I sometimes found these face-to-face meetings with constituents difficult, especially when criticism of me or the government was on the table. However, counter to that, on a significant number of occasions I revised my view of an issue when challenged by a constituent’s argument or narrated experience. That is democracy at work, interactive, negotiable and essentially free.

Third, the present system safeguards the bond between electors and elected. To my mind, pure form systems of ‘proportional representation’ (PR) threaten this. Characteristically, they involve multi-member constituencies with MPs elected from different parties. The danger is that during the course of a Parliament, voters will gravitate towards the MPs and the party they elected. As a result, neither electors nor elected are exposed to views that contradict their own. However much an MP may dislike conflict or disagree with a constituent, it is good and right for political positions and opinions to be questioned. There are, of course, other voting systems which combine PR with a direct constituency mandate, but it is hard to think of a (relatively large) democracy in which a busy MP will speak to and meet more constituents that in the UK.

Sir David Amess is not the only MP to have been killed or attacked in recent years: for many, this makes revision of the present pattern and protocols for security that much more urgent. MPs Sir Airey Neave (d. 30 March 1979), Rev Robert Bradford (d. 14 November 1981), Sir Anthony Berry (d. 12 October 1984) and Ian Gow (d. 30 July 1990) were all murdered during the height of the ‘troubles’ in Northern Ireland. More recently, Stephen Timms (MP for East Ham) was seriously injured in a knife attack in 2010, Rosie Cooper (MP for West Lancashire) was targeted by assassination plot in 2018, and Jo Cox (MP for Batley and Spen) was murdered by a far-right extremist in June 2016. What can be done to prevent this? Frankly, perilously little; especially if we want or expect MPs to be able to do their job properly and meet constituents freely.

That said, some measures have been, and should be, taken. After Jo Cox’s murder, many MPs stopped advertising the venues for their surgeries, and/or required constituents to ring and book an appointment. This simple act of screening minimises the risk of attack from a known assailant. For some, though, it undermines the principle of ease of access to MPs and does little to protect an MP from spontaneous violence or a terrorist attack. The idea some put forward that the police provide security at an MP’s surgery is met with a range of objections. Policing in the UK is already cash-strapped and over-stretched, to increase their regular workload to include protection of MPs (and other elected officials?) is almost unimaginable. What’s more, as intimated above, an MP’s weekly ‘surgery’ is only a small part in percentage terms (? 10%) of an MP’s work. There is no way protection could be provided for the rest of their life and work: even the Cabinet (other than the Prime Minister and the most senior ministers) does not have that. Furthermore, as the lethal stabbing by a terrorist of PC Keith Palmer GM (posth.) on 22 March 2017 confirms (he was on duty with the Parliamentary and Diplomatic Protection Group in New Palace Yard, Westminster), even supposedly secure locations – and with them the heart of democracy – are vulnerable to attack from extremists willing to die.

It may seem mine is a counsel of despair: that is not my intention. Several actions could be taken to increase protection for MPs and other public servants, none of which render them inaccessible to the public or constituents.

So, what can be done?

First, every threat should be reported and investigated. MPs tend to dismiss all but the most serious of threats as ‘just part of the job’. A more appropriate response might be to deescalate tension and active threat/s by increased reporting to the police and/or security service at an early stage. This is beginning to happen.

Second, MPs and other public servants (and their staff) need training in self-protection, and, as importantly, in self-awareness of threat. Much can be done in this area that would safeguard access and protect the public figure. Again, this is beginning to happen. After the murder of Jo Cox, additional advice was offered to MPs. My sense is, though, this may not have been taken sufficiently seriously – including, I must admit, by me.

Third, public rhetoric should be more muted. To my mind, politicians and other public figures have a duty to protect free speech by not abusing it. In short, they should be more careful with their language. Calling an opponent ‘scum’, or ‘vermin’, is not only rude and dehumanising it also sets a dreadful example for society.[1] In the run up to the Brexit vote (23 June 2016), talk of ‘treason’, ‘treachery’, ‘surrender’ and ‘sabotage’ was sadly not uncommon among politicians and pundits. Little thought was given to their impact on public perception and society’s well-being. Such language was, and is, entirely out of place in public life. It almost certainly poisoned debate over Britain’s departure from the EU and stirred animus towards MPs. Calls at the time for a ‘kinder, gentler politics’ in Britain were soon forgotten. Sir David Amess was an exceptional practitioner of a kinder, gentler – and note, no less effective – politics. Robust debate is integral to a vibrant democracy, but, as in the gentle sun of Aesop’s fable, persuasion is often more effective than windy bluster.

Fourth, the issue of social media anonymity needs to be closely scrutinised. Mouthing off without any kind of accountability cannot be right. I admit the issue is complex. Freedom of speech is a precious gift in a democracy. But there must be a way to protect free speech whilst clamping down on criminal abuse and inciting violence. There is a feeling among MPs and the wider public – in my view justified – that the giant tech companies who own and control social media outlets are still in dereliction of their duty when they deny there is a problem and that they are, at least in part, responsible for it.

Finally, we should not avoid – as, it seems, we are often at risk of doing – a proper national (and international) debate about the power of an ‘ideology’ to inspire violence and terrorist attacks, whether that ideology be religious (as in radical Islamism, Hinduism, Buddhism, or various politicised forms of fundamentalist Christianity) political (as in far-right nationalist movements) or any number of other extremist -isms. It is not enough to say, ‘This violence shouldn’t be happening.’ We need to understand, critique, and correct such behaviour as a responsible body politic.

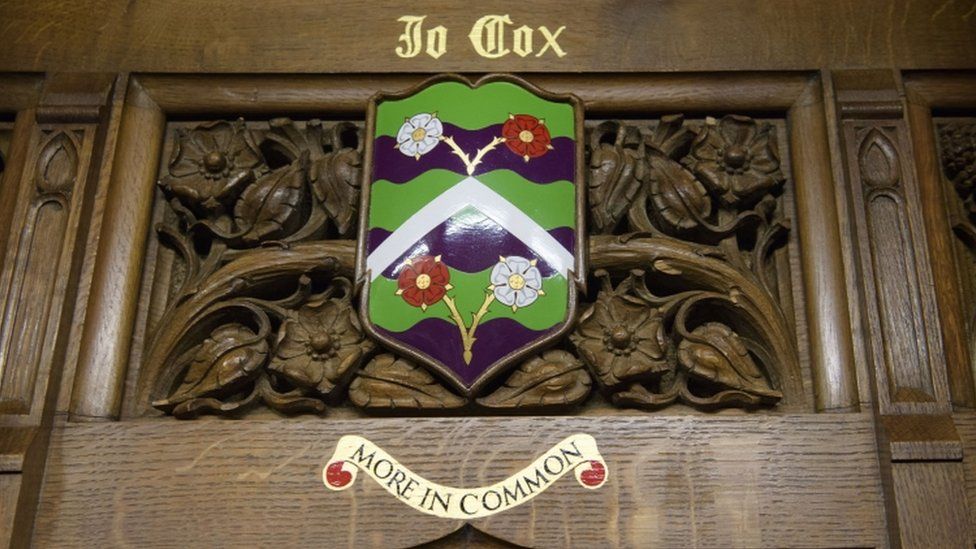

A shield commemorating Sir David Amess will be fixed to the wall of the chamber of the House of Commons. It will join others honouring MPs who were killed in the two World Wars, or, as we have seen, have been murdered more recently in the course of their public service. The shields are a constant reminder to those sitting in the chamber that their service comes at a price and with personal risk. It is a risk the public at large, who benefit from their work, must help to mitigate, and in such a way that MPs can continue to serve their constituents and country ‘without fear or favouritism’. Yes, there will always be some degree of risk in public life. In my experience MPs understand that risk and accept it.

Jeremy Lefroy, Associate

[1] The Deputy Leader of the opposition Labour Party, Angela Rayner (MP for Ashton-under-Lyne since 2015), with characteristic courage, offered on 29/10/21 an ‘unreserved’ apology for remarks made at the recent Conservative Party conference, when she called the Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, and other members of the Conservative Party ‘scum’. In an encouraging change of tone in political discourse, the Conservative Education Secretary, Nadhim Zahawi (MP for Stratford-upon-Avon since 2010) also welcomed the apology, tweeting: ‘Thank you for a message from the heart.’