Beware. If ever left alone in your study while you answer the door, take a call, or brew us a pot of tea, I am likely to betake myself to your bookshelves, often the best loved (and surely most interesting) part of many a home. Here you express yourself, reveal your passions and longings, and, if your ‘To be read’ pile is as tall as mine, admit interest outstrips efficiency if not spare time! Books, after all, reveal, laying bare the soul of a reader just as much as their theme. And in the randomness in which they sit astride our shelves mirroring lives thrown together in haste, tossed about in the maelstrom of postmodern culture, too rarely finding a way to name and order this new primordial ‘chaos’. Why, I ask myself, do American Robert Caro’s Working (2019), a fine volume of James Woodforde’s classic diary A Country Parson (fr. 1759), two books on Albania, and Miranda Seymour’s excellent study of ‘the turbulent lives of Lord’s Byron’s wife and daughter’, In Byron’s Wake (2018), sit beside one another on my window ledge? Not, I hasten to add, because they wait to be read! They lie like bands of sedimentary rock laid down in the passage of recent (reading) time. If we are what we eat, we are also, surely, in no small measure what we read … or nearly get around to reading. And this isn’t some esoteric Western thing: reading (even for those who sadly cannot) lies embedded in the cultural, political, spiritual and psychological substratum of life. All of us are – now as never before – what we read for good and ill, for leisure or work, by choice or by another’s dark design.

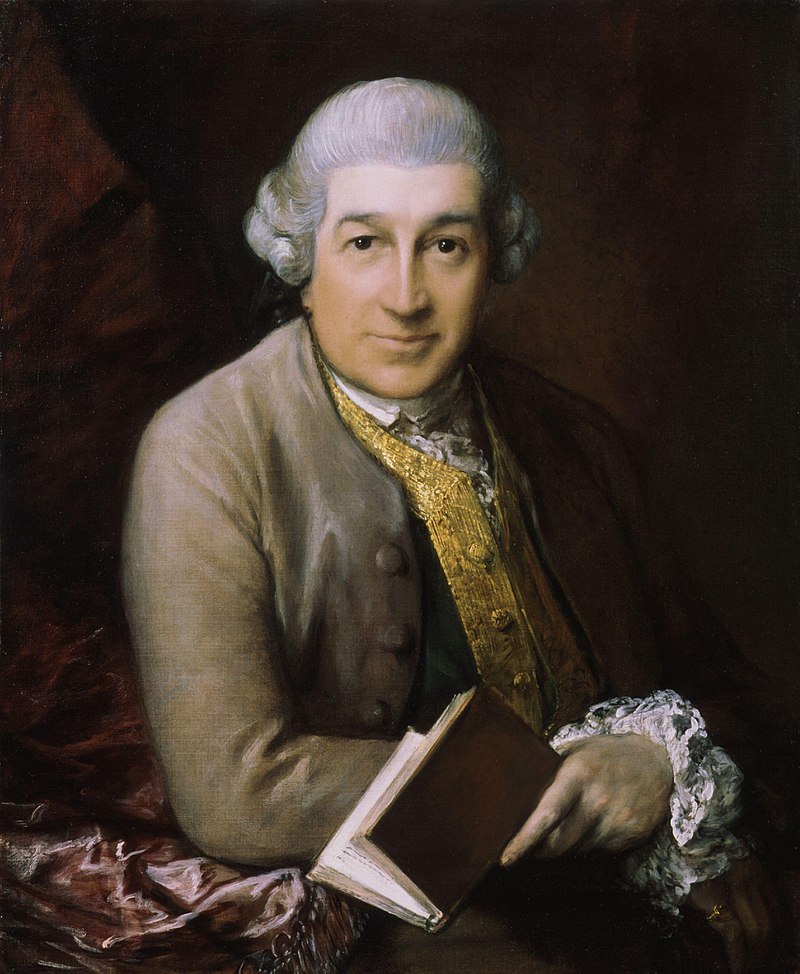

In the bookcase behind me, in which I unashamedly house books ‘To be read’ (!), I found a mint-condition copy of Richard Hough’s The Ace of Clubs: A History of the Garrick (1986). I cannot remember buying it and am not a member of that most delightful of London clubs (founded in 1831), historically for patrons and practitioners of drama, but now serving an eclectic community of interested and interesting people in London’s West End. But there the book sits on my shelves between Niall Ferguson’s brilliant The Pity of War: 1914-1918 (1999; which I have read), Christopher de Hamel’s Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts (2016; which I have not yet!), a recently purchased Chinese-English New Testament and Alfred Regnery’s stimulating narrative of his ‘spiritual travels’, Unlikely Pilgrim (2019; which I read in draft). Books, like lives today, seemingly ‘thrown together in haste’ – but not, like many of our book purchases, without some deeper rationale in the depths of our psyche. The 18th century Shakespearean actor, playwright, and impresario David Garrick (1717-1779) – whose birthday was yesterday – put Stratford-upon-Avon on the map: perhaps for this alone he deserves to be named in a London club (and theatre)! But, like the books on my shelves, Garrick lived an eclectic life that I have always found fascinating. I will come back to him in a moment. The other reason Hough’s book The Ace of Clubs is on my shelves, is to know more of the place where I have lunched (lavishly) with a dear friend many times over the years. For, as good books and friends remind us, ‘Man does not live by bread alone’ (Deuteronomy 8.3; Matthew 4.4). There is more, far more, to life than that.

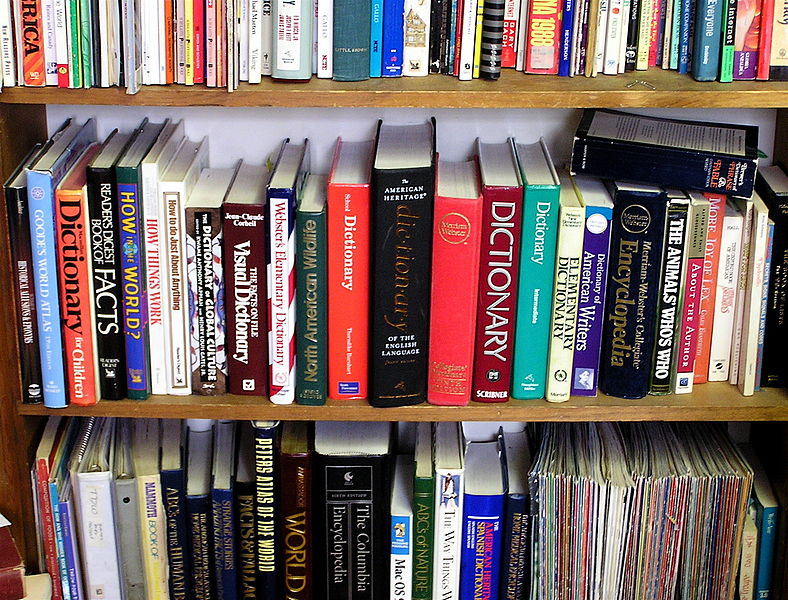

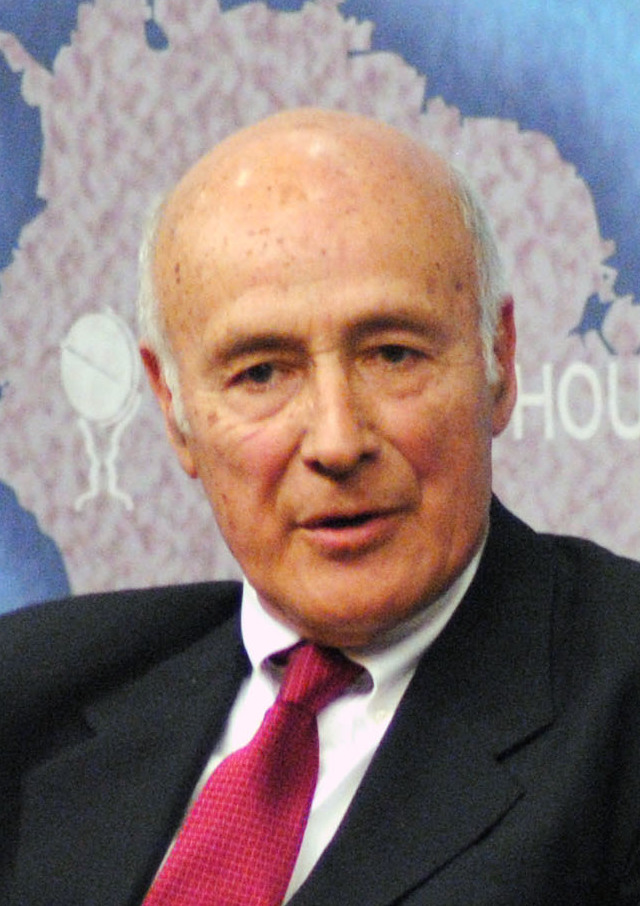

In the late 1980s, the American political scientist Joseph Nye (b. 1937), who served under President Bill Clinton (b. 1946) as Chair of the National Intelligence Council (1993-4) and Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security (1994-5) and was subsequently Dean of the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University (1995-2004), introduced the term ‘soft power’ into political and diplomatic discourse. Prior to this Nye and his colleague Robert Keohane (b. 1941) had begun to speak of ‘neoliberalism’ and the complex, asymmetrical ‘interdependence’ of state systems and human institutions; notably in their book Power and Interdependence (1977). In 2004 Nye gathered his thoughts in his book Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. He followed this, in part reacting to criticisms leveled against his earlier work, with The Future of Power (2011). Nye’s work has a place on many shelves, and rightly so. In terms many have grasped and owned, Soft Power distinguished – to critics, weaponized – the difference between a politics and diplomacy (indeed, comprehensive way of relating to others) based on ‘hard power’ coercion and ‘soft power’ co-option. The end is the same (viz. getting someone to do what I want), the means quite different (encouragement rather than enforcement). As Nye unpacks what makes for a state’s ‘soft power’ in his later work: ‘its culture (in places where it is attractive to others), its political values (when it lives up to them at home and abroad), and its foreign policies (when others see them as legitimate and having moral authority)’ (The Future of Power, p. 84). In other words, attractiveness leads to amenability which leads to accomplishment. Here is Nye in an article ‘Public Diplomacy and Soft Power’ (Annals 616, March 2008: 94):

A country may obtain the outcomes it wants in world politics because other countries – admiring its values, emulating its example, aspiring to its level of prosperity and openness – want to follow it. In this sense, it is also important to set the agenda and attract others in world politics, and not only to force them to change by threatening military force or economic sanctions. This soft power – getting others to want the outcomes that you want – co-opts people rather than coerces them.

Or, as he says in Soft Power, ‘Seduction is always more effective than coercion, and many values like democracy, human rights, and individual opportunities are deeply seductive’(p. x.). In other words, enviable culture, estimable political ‘values’ and effective policies can be as, if not more potent than bullying words, brandishing arms and b-minded belligerence.

The idea and use of ‘soft power’ have been subject to close scrutiny and sustained criticism. Two issues stand out for comment. First, by its very nature ‘soft power’ is more difficult for a government to ‘manage’, either as its ‘proponent’ (relying on the full range of unofficial, informal, and personal cultural and humanitarian ‘assets’ to advance its agenda) or as its ‘object’ (being faced by forces and inducements that lure, lull and secure good will inside and outside government, viz. US AID in conflict regions, African hospitals built with Chinese money, Bollywood films with an enculturated political message). In short, ‘soft power’ is, to some, making the ‘virtue’ of diplomatic, or cross-cultural, understanding out of the ‘vice’ of the way the intersecting, mutually conditioning, world of culture and politics has been and always will be. Second, naming and claiming ‘soft power’ strategies is either diplomatically naïve or strategically dangerous. It tips the ‘proponents’ hand: it educates an aggressive foe. What’s more, as Nye himself admits, ‘Hitler, Stalin and Mao all possessed a great deal of soft power in the eyes of their acolytes, but that did not make it good. It is not necessarily better to twist minds than to twist arms’ (The Future of Power, p. 81). Let’s be clear, ‘soft power’ is not per se moral. Lacking direct accountability to public or democratic scrutiny, seduction, inducement, spin, biased PR, shady quid pro quos and whispered promises, may all corrode and not enhance diplomacy and trust. The globalizing of ‘soft power’ strategies in the early 20th century may have had this effect; indeed, served to fuel the ‘hard power’ ‘strong man’ style of a Trump, Putin, Xi, Macron and Erdogan. The Book of Proverbs is again surely right, ‘Better open rebuke than hidden love’ (27.5). Let’s not doubt, openness also works.

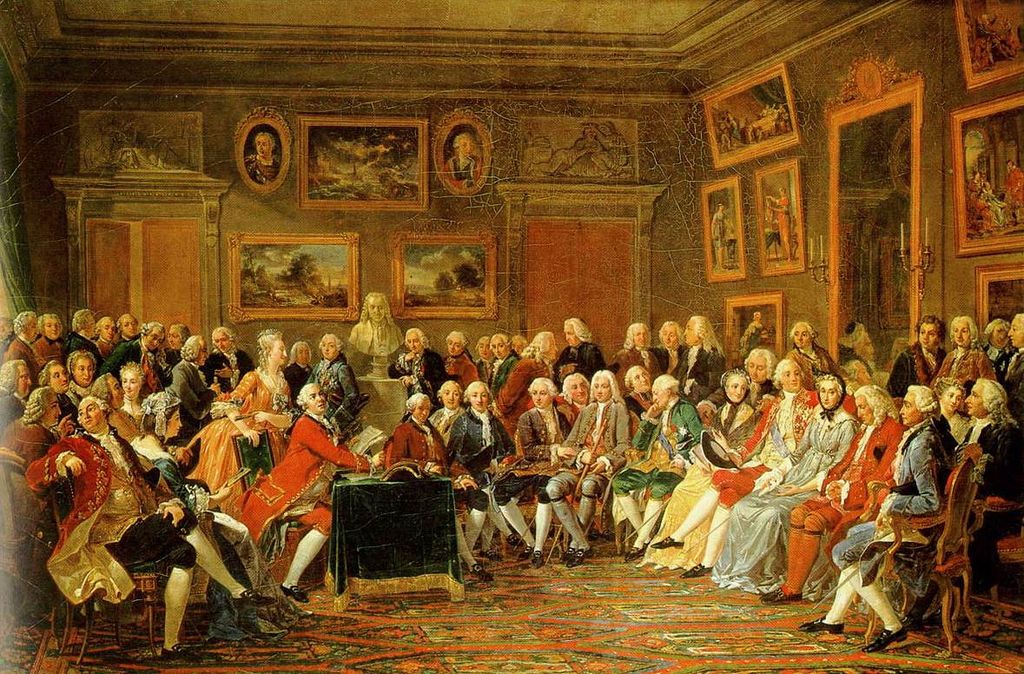

(By Anicet Charles Gabriel Lemonnier – Web Gallery of Art)

Come back to Garrick. I don’t want despair at contemporary manifestations of ‘hard power’, or cynicism at the proliferating use of ‘soft power’, to compromise his reviews. He is, to my mind, a gifted exemplar of ‘soft power’ diplomacy of the most enlightened and engaging kind. Few of us would not enjoy dining with him at his club, or wherever else his extensive travels took him. Here was a pupil and friend of the learned literary and cultural icon Dr Samuel Johnson (1709-84), who said of Garrick (to the dismay of impoverished thespians ever after!), ‘His profession made him rich and he made his profession respectable.’ Though reckoned a poor playwright himself, here was the reviver of Shakespeare and confounder of Georgian melodramatics, the recoverer of late-17th century ‘Restoration’ theatre and manager (for almost 30 years) of the Drury Lane theatre company. Here, too, was a regular visitor to the ‘enlightened’ salons of Parisian ‘high society’, where (as in London) he rubbed shoulders with the likes of François-Marie Arouet (aka Voltaire; 1694-1778) and Baron d’Holbach (1723-89), Baron Charles-Louis de Secondat (aka Montesquieu; 1689-1755) and Benjamin Franklin (1706-90), and literary and political luminaries David Hume (1711-76) and Adam Smith (1723-90), John Wilkes (1725-97), Horace Walpole (1717-97), historian of the decline of Rome Edward Gibbon (1737-94) and Anglo-Irish novelist Rev. Laurence Sterne (1713-68). Though professionally inhabitant of one ‘world’, Garrick culturally and intellectually inhabited many ‘worlds’, and thereby united them. As his mind, work and reputation grew, the Channel and Atlantic contracted. Such was his exercise of ‘soft power’, played out on arguably the fiercest stage of socio-political unrest the West has ever seen.

A quiet lunch in the Garrick Club with a mouthful of tender beef and splash of fine red wine, can seem a million miles from the life and world of John Garrick himself. Not so, of course. For to me, as for so many, a meal there is a reminder again that ‘Man does not live by bread alone’, but by friendship and conversation, listening and learning, mutual stimulus and bracing dialogue, art and theatre, the quest for truth and love and ‘charity’. In the face of such ‘goods’, the exercise of ‘hard power’ and trickery of ‘soft power’ pale into insignificance. Remember Garrick next time you tuck your napkin under your chin, sit down to a play, or shimmy books along your over-full shelves. It is at times in the unexpected and eclectic, in the over-looked and under-valued we find and, perchance even exercise, ‘true power’. Such a ‘read’, like any good book, changes the way we see life, our life; and, dare I say, play it out on the small stage of our own little world.

Christopher Hancock, Director