I had a wonderfully astute assistant some years ago. When asked a question she couldn’t – or sometimes didn’t want to! – answer, she would shrug her shoulders, like the delightful (but very dumb!) Spanish waiter Manuel in the British comedy series Fawlty Towers, and say winsomely, ‘I know nerthing’. It always lightened the mood in the office: ability veiled is so much more attractive than confident conceit. And, of course, my colleague had ancient wisdom on her side. Her words echo the famous ‘Socratic paradox’ that Plato (ca. 425–ca. 347 BCE) cites in both the Apology (399 BCE) and Meno (ca. 402 BCE). A visit to an Oracle to find wisdom leads to the conclusion: ‘I seem … in just this little thing to be wiser than this man at any rate, that what I do not know I do not think I know either’ [H. Cary trans. 1897]. The knowledge of politicians, poets and craftsmen is, to Plato, likewise deficient by its presumption, scope and depth. Knowledge is always (to some irritatingly!) a cousin of virtue: the wise honestly admit ‘I know nerthing’, fools conceitedly say, or think, ‘I know it all.’ But the difference between them can be almost imperceptible. Close attention is needed.

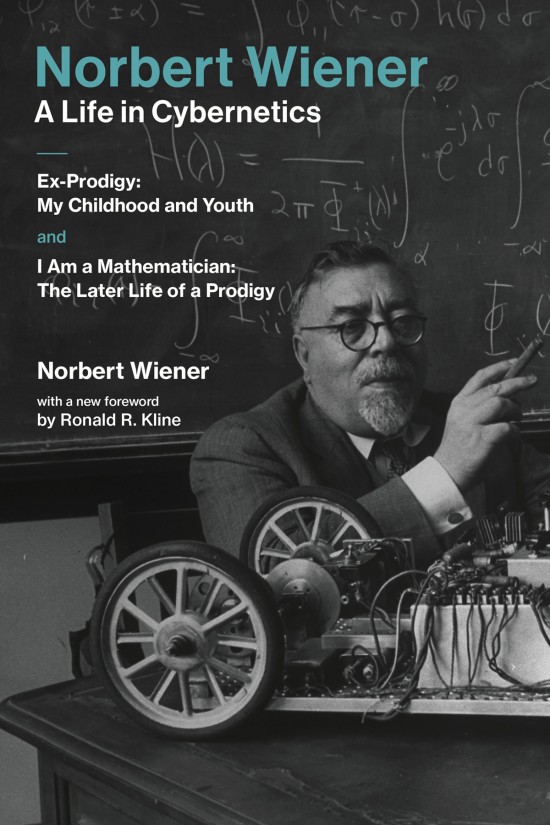

‘Knowledge’, it is often said, ‘is power’. Think of the world-changing impact of semiconductor technology and development of the integrated circuit chip and metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor. Knowledge – immense knowledge – made possible by a tiny processor. To some, the ‘Information Revolution’ of the 20th and early-21st century that this new, power-filled knowledge has unleashed is comparable to ‘matter’ and ‘energy’ as a new, constituent part of our Universe. The American philosopher-mathematician Norbert Wiener (1894-1964) anticipated this in his book Cybernetics (1948): ‘Information is information, not matter or energy.’ In this new tech world, it is not just ‘knowing’ that has power: it is the progressive evolution and institutionalization of machines and systems that define – and increasingly determine – the kind of people and world we are. It is no surprise information technology and cyber security are mainstream disciplines for countries, corporations, universities, and research bodies: information – in all its coded, sorted, compacted, processed forms – is the lifeblood of our postmodern world. And, as the ancient Jewish sacrificial system taught the world, ‘The life is in the blood’ (Leviticus 17.11). Tech-knowledgy has become now for many people life itself: its absence political, social, economic, and military disempowerment, parochial cultural desiccation, or that unnamed corpse by the roadside as the trucks of scientific and cybernetic progress hurtle by. Knowledge, as Plato saw, dangerously and illogically disengaged from virtue.

If the full impact of the ‘Information Revolution’ is still to be felt – and may not be for decades to come – it is not too early to cross-examine some of the potential (in some cases already actual) implications of it. The questions we ask here are crucial; indeed, they may directly affect humanity’s capacity to cope with the ‘information’ it generates or the new types of machines that ‘information’ creates. Like ‘matter’ and ‘energy’, ‘information’ belongs to a world of human enquiry that can, and should, dissect, process, harness and evaluate it. The full range of human interests and skills must be deployed here lest this new ‘information’ be privileged and unaccountable in ways ‘matter’ and ‘energy’ never have been – thank God!

So, where do we begin? It is not easy or obvious. How do we get a handle on the ‘Information Revolution’ when by design it quarries the frontiers of human knowledge and does not want, or intend, to be shackled? How do you dance with this bear, who isn’t worried about treading on your toes and is more interested in his next dinner than having a conversation with you? Let me suggest three strategies: none, I assure you, extend the already strained bear analogy!

i. History. The postmodern ‘Information Revolution’, though known for its new technologies and human possibilities, is not without precedent. It sits within the ‘History of Ideas’. It is part of an evolutionary process of human discovery on a well-charted path of cultural and intellectual development. It has historical antecedents; claims to ‘breaking new ground’ to be viewed with the wary eye of the historically alert and, if Plato is right, morally sensitive. After all, knowledge per se doesn’t have an impeccable record. Humans have learned – and tried to learn – better ways to kill and destroy, to manipulate and control, to lie and deceive. Scientific advances have been impressive, humanity’s progress to self-understanding less so.

The historical roots of the post-industrial ‘Information Revolution’ run deep; to the complex interaction of knowledge with culture, tribe, and cultivation in the development of primitive agrarian communities, through the great schools of human learning and inquiry in classical antiquity (viz. the 4th-century BC Platonic Academy and Aristotelian Peripatetic School, the creation of the great Library and Museum in Alexandria in the 3rd century BC and the system of ‘schools’ or Lyceums they spawned across Europe) that categorized ideas and framed traditions of thought for millennia, to the burgeoning of technical skills that drove the urbanizing energy of 18th and 19th century ‘Industrial Revolution’. Humanity’s hunger to learn is striking, as are the twists and turns, reverses, and rejections, in our story of learning. Who now really believes the once influential Marxist reading of British crystallographer J.D. Bernal’s (1901-1971) The Social Function of Science (1939), or Czech philosopher Radovan Richta’s (1924-1983) Civilization and the Crossroads (1969), and sees socialism as the safest home for science and technology? And anyway, the ‘post-industrial society’, the American sociologist Daniel Bell (1919-2011) foresaw, in his The End of Ideology (1960), The Coming of Post-Industrial Society (1973) and The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism (1976), is more akin to the ‘service economy’ we associate with the ‘Information Revolution’ in the West than the authoritarian technocracies of the former USSR or presently aggressive China. In short, we get a handle on the ‘Information Revolution’ when we set it in an historical context and work to evaluate and use it as judiciously as we have ‘energy’ and ‘matter’. Why? Because, surely, wisdom sees these as elemental forces that can make or break our world.

ii. Universities. A second way to get a handle on the ‘Information Revolution’ is via the idea of a university. Knowledge is after all their shared currency, culture, politics, and society their common habitat. But we must tread with care. Other bears live here! So, three simple points.

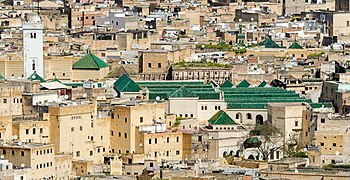

First, the history and diverse ethos of universities are a reminder that knowledge is culturally conditioned. Though Bologna is traditionally the oldest university in Europe (ca. 1088), other institutions of higher learning existed centuries prior to this in Greece, Rome, China, India, Africa, Byzantium and throughout Persia and the Islamic world. According to UNESCO, the Islamic University of al-Qarawiyyin in Fez, Morocco, which was founded between 857-859 CE by the young Fatima Al-Fahri (ca. 800-ca. 880 CE) and joined the state system in 1963, is the oldest in the world. In Europe from the 6th century onwards, Roman Catholic monastic and cathedral ‘schools’ laid a foundation for later universities like Oxford (ca. 1200-1214), Cambridge (ca. 1209-1225), Salamanca (ca. 1218-1219), Padua (1222), and Naples (1224). Faith and culture shaped these institutions. Mind, body, and soul were integrated in their pedagogy. But let’s be clear, information is never – as humanists and empiricists might want or hope – culturally or rationally ‘pure’: it is affected and infected by those who seek it and by those claiming to find it. The ‘Information Revolution’ is no exception. It is full of prejudice and bias, aggression and greed, ambition and distortion. It rarely admits with Manuel, Plato, and generations of devout academicians who filled the first universities, ‘I know nerthing’.

(By Lithographie von Friedrich Oldermann nach einem Gemälde von Franz Krüger)

Second, the history and variety of universities are a reminder, in the midst of the ‘Information Revolution’, that knowledge is contested. Marked differences emerged in the early 19th century between the holistic formation of social and professional elites trained in age-old disciplines, characteristic of the Oxbridge model, and the ideas embodied in the new University of Berlin (founded in 1810) by the philosopher, linguist, diplomat, and bureaucrat Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767-1835). The ‘Humboldtian’ idea, which subsequently dominated European and N. American thinking, was of a ‘union of teaching and research’ in which scholars and students would share a common quest for truth and knowledge. Serious work done by serious people. Though not immune to political pressure, social elitism, and intellectual fads, it was this idea that shaped leading universities around the world until a vision for mass higher education, at the end of the 20th century, challenged and refined it. Lack of uniformity in the idea of a university is a tangible, intellectual reminder that knowledge and information transfer have not been – and never are – above criticism and correction. A neo-fundamentalist notion that the ‘Information Revolution’ is generating knowledge that is, or should be, uncontested, is palpably balmy – and dangerous. Like ‘energy’ and ‘matter’, ‘information’ has raw elemental power. Knowledge is what you find and what you make of it: in the process, all kinds of societal, philosophical, political, and ideological ‘interference’ occurs … for good and bad.

Third, the ‘Information Revolution’ is reminded by the history and evolution of universities that knowledge is holistic. It requires (self-)understanding and technical ability, rationality and relationality, data accumulation and honest discovery. In 1963 the UK Government commissioned ‘Robbins Report’ subjected the Oxbridge model to critical scrutiny. Radical changes to Britain’s vision for its universities emerged. The so-called ‘Robbins Principle’ set about democratizing higher education (as a broad, open path to productive citizenship) and technocratizing it (with ‘instruction in skills’ to match ‘intellectual discovery’). Over time, research acquired pivotal prominence (not least, for the funding and evaluation it attracted) and ‘residence’ became a pedagogical (and moral) principle and priority, not the right of the privileged. Red brick universities were squeezed, new universities born, old technical colleges renamed. The seeds of the ‘Information Revolution’ were sown in the soil of this new vision for mass learning and open enquiry. As Robbins saw, pedagogy shapes professions.

iii. Inquiry. Hegemonic claims by ‘Information Sciences’ sit ill with a holistic vision of a ‘Liberal Arts’ education and a rich ‘campus experience’. Indeed, as the doyen of ‘the idea of a university’, Cardinal John Henry Newman (1801-1890), argued first in five lectures he delivered in Dublin in 1852, universities should reflect the nature of knowledge (in which ‘tradition’ is critically examined), the priority of the ‘soul’ (as central to true ‘understanding’) and the sovereignty of ‘truth’ (which is strong in the face of scrutiny). As Newman memorably wrote: ‘[T]he very name of University is inconsistent with restrictions of any kind’. And again, ‘What I would urge upon everyone, whatever may be his particular line of research – what I would urge upon men of Science in their thoughts of Theology, what I would venture to recommend to theologians, when their attention is drawn to the subject of scientific investigations – is a great and firm belief in the sovereignty of Truth’. To Newman, and the many who have heard wisdom in his words, there is no ‘university’ without multi-disciplinarity, a sense of community, and a humble, honest quest for knowledge and truth. The ‘Information Revolution’ is, surely, rightly critiqued by this holistic idea for a university and open view of human inquiry – just as ‘energy’ and ‘matter’ are to academic multi-disciplinarity (including ethics and ecology) and moral responsibility (including to privacy and human rights). Data is insecure when pilfered by governments, corporations, and pesky hackers, yes: it is also at risk fromunfettered application and immoral usage. ‘Information’ is not a moral ‘free zone’ where every use and every discovery, is unambiguous.

Last, and here I return to my title, ‘The conceit of learning’. Academic excellence is built on fine margins and clear distinctions. The clarity with which Plato rumbled the inadequacy of the Oracle’s view of knowledge is inspiring. To specialists, it reflects the kind of sensitivity needed to distinguish between ‘conceit’ (as in character description) as the height of hubris and ‘conceit’ (as used in historic literary analysis) as the essence, or essential (albeit veiled) meaning, of a poem – or, we might say now, with Newman in mind, the soul of an institution. Too often, alas, in the midst of the ‘Intellectual Revolution’, the ‘conceit of learning’ is more often aptly applied to pride in technological discovery than principled humility that can say – with Manuel of Fawlty Towers and my fine, winsome assistant – ‘I know nerthing’, in the face of new information’s raw, elemental power. Here, too, through sacrifice comes life.

Christopher Hancock, Director