Immediate issues have magnetic power. It can be hard to resist their pull. Pressing matters in international relations dominate minds and media coverage: North Korean missile tests, meetings between Xi Jinping and US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken (b. 1962), Vladimir Putin’s clash with Wagner Group leader Yevgeny Prigozhin (b. 1961), the catastrophic loss of migrant lives in a fishing boat accident in the Ionian Sea (June 14), G7 leaders’ meetings and discussion of the expansion of NATO (July 11/12). Significant issues, of course, but larger issues and broader questions are often neglected. In light of World Refugee Day (June 20), what of the 2062 (est.) migrants who drowned in the Mediterranean in 2022? What of the impact on the balance of geopolitical power and ecological crisis of the strengthening Sino-Russian axis? What of the reaccrediting (by some) of Bashar al-Assad’s (b. 1965; Pres. 2000-present) hold on Syria, or warm mood music from Beijing on China’s relationship with Iran, or America’s courting of India and Narendra Modi, or the faltering influence of the Roman Catholic Church in Latin America? And so one might go on. Vast mega-trends, some new some old, demanding attention, too often down-played.

To medics, symptoms are significant; more significant, are their underlying causes. Treating the former risks aiding and abetting the latter. Geopolitical analysis should never settle for headline news and symptoms: it must find and address root causes. In the words of a wise calendar on my desk, this comment on Proverbs 18.1 (‘He who is estranged seeks pretexts to break out against all sound judgement’): ‘Look for the reasons behind a friend’s harsh words not in the force of his argument but in the state of your relationship.’ In short, the presenting issue may not be the real issue. Simplistic commentary on the ‘health’ of a nation or state of the world, will not do. Deeper diagnostics are required. Thankfully, new resources are on hand to give depth and breadth to our understanding.

Two books with similar titles appeared at the start of this century; both, in different ways, anticipate later events. In September 2001, the US-based Canadian academic Andrew Price-Smith (1969-2019) published his inter-disciplinary study The Health of Nations: Infectious Disease, Environmental Change, and Their Effects on National Security and Development. As the title suggests, Price-Smith’s work is in the emerging fields of health and environmental security. He posits variables (of every kind) states must anticipate when facing a pandemic. Complex linkages create a new, fluid, state for states. Politicians, economists, and historians can learn much, belatedly, from Price-Smith’s prophetic work. The second work, by Harvard social epidemiologists Bruce P. Kennedy (d. 2006) and Professor Ichiro Kawachi (b. 1961), was The Health of Nations: Why Inequality is Harmful to Your Health (December 2002). This book also tracks linkages, now between social justice and physical and political ‘health’. If, or when, we are tempted to think of ‘the state of the union’ in purely political or economic terms, both books disabuse us of this limited and limiting notion. ‘The health of a nation’, and ‘the health of nations’, are far more complex, fluid, vulnerable, realities. Geopolitical analyses that focus on immediate risks miss ‘security’ threats of other, potentially far more serious, kinds. Of course, it is impossible to anticipate every threat and mitigate every risk, but projecting scenarios and modelling impacts are becoming easier with sophisticated modern technology – to say nothing of the role AI may play in futurology!

The Scottish Enlightenment philosopher-economist Adam Smith’s (1723-1790) seminal study An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations,otherwise known as The Wealth of Nations, was published in two volumes in 1776. This classical study of the dynamics of markets and the power of healthy competition, is not only evoked in the titles of Price-Smith’s and Kennedy & Kawachi’s work, it is also emulated in their careful quest for, and naming of, broader and deeper forces that shape and threaten the body politic. To Smith there is an ‘invisible hand’ in markets that acts ‘naturally’ to regulate the pricing, decision-making and competitiveness of production and producers. As often noted, Smith’s Wealth of Nations followed chronologically, and depended intellectually upon, his earlier study The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759). To Smith, economic projections that fail to reckon with the moral – and psychological – ‘nature’ of humanity, society, and economic activity, will be deficient. The ‘symptoms’ of human production and competition are to be explained by deeper motivational ‘causes’. This holistic approach is reflected in the inter-disciplinarity of Price-Smith, Kennedy and Kawachi. If ‘natural liberty’ (viz. ‘health’), on which a dynamic market (viz. ‘wealth’) depends, is compromised by what Smith calls ‘the mean rapacity’ and ‘the monopolizing spirit of merchants and manufacturers, who neither are, nor ought to be, the rulers of mankind’, disease (Price-Smith) and injustice (Kennedy & Kawachi) similarly threaten the health and wealth of states. Deep analysis of the ‘health of a nation’ will push out the boundaries of understanding and be ready to incorporate data that some may find unacceptable. Our systemic failure to anticipate a global pandemic or war in Ukraine should caution against over-confidence that all eventualities have been considered!

The ‘health’ of a nation is, I suggest, inseparable from its ability to communicate. Effective internal communication bolsters policy and the position of policymakers. The converse is also true: poor communication hobbles leaders and eviscerates their power. But effective external communication is also vital. Poor international PR and ill-informed diplomacy are the scourge of global harmony and intercultural understanding. The state of states is bound up with their ability to understand, to be understood, and to make themselves intelligible to others. Bully boy tactics do not make for good communication; nor does a will not to grasp what someone else is saying. To echo Adam Smith, the ‘relational economics’ of responsible societies will keep a close eye on the ‘nature’ of their internal and external communication, lest ‘mean rapacity’ and a ‘monopolizing spirit’ be permitted to hold sway. As noted above, the presenting issue may not be the real issue! Effective communication is inseparable from a strong grasp of the meaning and (potential) interpretation/s of words. It relies on sound study of the social freighting, technical use and gradual evolution of words, ideas, concepts, and phrases; indeed, the health and wealth of a nation are, I would argue, inseparable from its understanding of the multiple uses, and ever-expanding meaning, of one key word, ‘state’ (Lat. status; lit. condition, circumstance).[1]

In keeping with the interdisciplinary quest for deeper dynamics (‘linkages’) we have seen in Adam Smith, Price-Smith, Kennedy and Kawasi, I want for the remainder of this Briefing to consider the semantics of the word ‘state’ and propose ways a richer understanding may promote the ‘health’ and ‘wealth’ of nations. Central to my argument is that the ‘state’ of ‘states’ matters; that, if you like, the ‘health’ (and ‘wealth’) of nations is far too important to be left to chance – let alone to the supposed professionals!

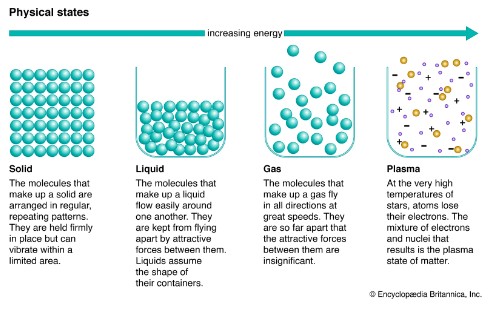

Physics identifies four ‘states’ of matter (viz. solid, liquid, gas and plasma) and, more recently, numerous intermediate states (i.e., liquid crystal) or ‘exotic’ states, i.e., ‘Bose-Einstein condensates’ in extreme cold and those associated with extreme density (neutron-degenerate matter) or energy (quark-gluon plasma). The number of listed states of matter has increased exponentially in the last few years with some studies listing no less than 22.[2] To use the word ‘state’ of matter is now an intensely complex, fluid – and interesting – issue.

The word ‘state’ is, of course, not only used by physicists or material scientists. Common parlance speaks of a ‘state of mind’, of a person on a bad day ‘getting into a state’, of the state of a given company or country’s finances and of the disheveled state of a person’s dress or appearance. Likewise, publishers speak of the number of states of an edition, cricketers of the state of a pitch, lawyers of a client stating their case and musicians of a composer’s introduction of a theme. Politically, ‘states’ impose rules, protect citizens, marshal resources, pay ‘state visits’, and respect deceased leaders with a ‘lying in state’.[3] Used as a verb when a person or a document ‘states’ something, they are heard to do so with clarity, authority, and intent. In short, whereas modern physics and material science use ‘state’ of a plurality of varied and variable phenomena, historic, every day, and institutional use connotes solidity and permanence, if not inflexibility and decisiveness. This contrasting usage warrants close attention, lest the problems and possibilities of an exchange of meanings be missed.

Why, you may ask, track the meaning and use of a word in this way? For a number of reasons.

First, because words consciously and unconsciously shape worlds. Use – as ‘political correctness’ has reminded us – must be monitored lest blurred and/or evolving meanings change or misrepresent reality.

Second, because in this instance the (habitually dominant) world of science is (unusually) subservient to the everyday and institutional. Of course, some commentators use the terms ‘solid’ and ‘fluid’ to expound and evaluate the strength and weakness of historic institutions like the church or political parties, but deeper reflection on the problems and possibilities of interfacing popular/institutional use and specialist scientific freighting of words such as ‘state’ or ‘states’, is surprisingly rare.

Third, following on from this, the academic discipline of International Relations has become increasingly conscious of the value of engaging the Social Sciences. Sociology, anthropology, psychology, ethnography, culture studies, and linguistics, for example, have shed invaluable light on East-West relations, terrorist motivation, minority identity, and the changing roles of women and girls at home and in the workplace. Reflection on the meaning of ‘state’ and ‘states’ is a further instance of wholesome interdisciplinarity.

Fourth, as we have seen, ‘state’ has an extraordinary breadth of meanings and applications. It takes us into a person’s persona and behaviour. It opens the door into the structure and priorities of the ‘corridors of power’. It inhabits and impacts culture and literature, pastimes, and pleasures. It summarizes a political system (viz. ‘the States’ of America or government of the island of Jersey) and a field of play. Few words have such reach.

Lastly, it is worth reflecting on the multiple meanings and uses of ‘state’ and ‘states’ because their psychological and behavioural connotations (viz., ‘state of mind’, or ‘to be in a state’) suggest important questions to ask about the impact of life and context on an individual and their society. The ‘state’ of a nation now becomes a bigger issue than its balance sheet or military strength. Psychological and behavioural associations of ‘state’ and ‘states’ intensify the warnings of Adam Smith, Price-Smith, Kennedy and Kawachi that the context and content of decisions must be broadly conceived and carefully cross-examined; that is, in today’s terms we might say, ‘deep reading’ is as important as ‘deep listening’.

So, what are the takeaways from all this? Let me suggest four things briefly, in light of recent events and on-going debate about outsider intervention in the affairs of sovereign nations.

First, though in common parlance a nation ‘state’ implies a solid institution and identifiable region, political ‘states’ are infinitely varied and fluid.[4] Boundary changes, border disputes and a ‘revolving door’ into and out of government suggest change is in many countries the only political constant. To those advocating a ‘solid state’ view of government and national life, such ‘fluidity’ is a source of concern and sign of weakness. The plurality of ‘states of matter’ that modern physics and material science recognize should, I suggest, encourage a more positive response, with a plurality of governmental systems not a sign of weakness but a potential source of strength and life. New materials with new ‘states of matter’ can be both incredibly flexible and phenomenally strong. Projecting – and expecting – one system of government to ‘fit all’ does not sit well with modern physics and material science; more than that, when culture, ethics and spirituality are factored into International Relations and diplomacy, we have other criteria to draw on in describing and developing the ‘health’ and ‘wealth’ of a nation. The imposition of ‘solid’ (but often palpably ‘unhealthy’) Western views of government on ‘fluid’ (but vibrant) young nations risks spreading infection and stunting growth. In political and diplomatic terms, a ‘state’ is not, and should rarely be, a ‘given’.

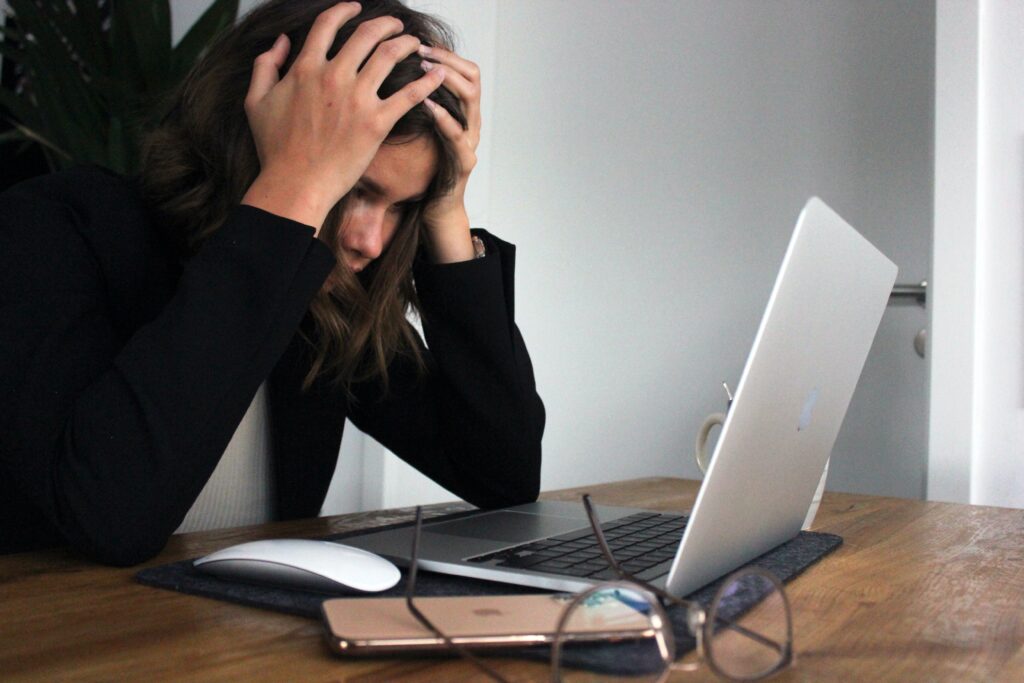

Second, if physics and material science push out the meaning of ‘state’ in one direction, the behavioural and psychological sciences suggest another. They remind us that the ‘state of a state’ involves its spirit and mindset, its culture and well-being, its self-esteem and sense of vulnerability, its social harmony or lack of it. Nations can be psychologically ‘in a state’ and ‘get into a state’ in a political scandal or in the run-up to a presidential or national election. Nations possess a persona and a psyche. A mind and (sometimes tortured) soul inhabit the flesh and bones of their historic institutions. The ‘state of states’ affects leaders, residents and outsiders. National optimism or its obverse, a depressed state, impact investment and vision, coherence and self-confidence. As the Book of Proverbs warns, singing songs to the depressed is to pour salt on open wounds. Likewise, a leader like President J. F. Kennedy (1917-1963; Pres. 1961-63), who captured the spirit of a nation on the ascendant, can ride the tide of popular support. More questions might, I believe, be rightly asked of aspirant leaders, ‘Do they understand the state of our nation?’ and ‘What state will they leave our state in?’ Emotional intelligence in leaders helps them discern the heart and soul of their followers. Shallow, ambitious, bureaucratic national leaders have little concern for such.

Third, following on from the previous point, concern for the ‘health’ and ‘wealth’ of a nation will be expressed in attending to its ‘body’ and its ‘soul’, its institutions and its psychological well-being. Alas, current sensitivity to ‘mental health’ rarely goes beyond the individual to the corporate, from a person to the ‘system’ they inhabit; when, of course, ‘mental ill health’ often has some kind of institutional cause. But let’s be clear, ineffective government, self-interested leadership, fiscal pressure, corporate mismanagement, social inequality, and long-term unemployment, are more than ‘institutional’ problems: they affect the ‘health’ and ‘wealth’ of a nation per se. Read in this way, close study of ‘the state of a state’ will look at its ‘system’ of government and its social, psychological, and moral welfare. Sick countries and cultures don’t happen by chance: they reflect a consistent – often willful – failure by leaders and led, to ask the right questions. Adam Smith was right to focus attention on the psychology of markets and on the potential of ‘mean rapacity’ and ‘the monopolizing spirit of merchants and manufacturers’ to corrupt and corrode them. Critical reflection on the ‘state of a nation’ as a whole requires a similar focus and a readiness to confront mistakes.

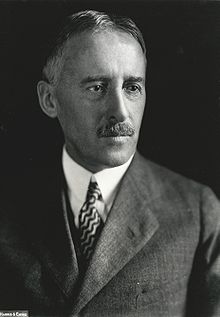

Lastly, lest the preceding point suggests the ‘state of a state’ be reduced to its ‘state of mind’ or ‘state of heart’, a state is also a statement of intent and an act of will. Put simply, a state is rightly stated to be ‘X’ and not ‘Y’, as a deliberate decision and indication of direction. The importance of recognizing this principle maps on to a theme alluded to earlier; namely, the degree to which a country has the right – or, indeed, a responsibility – to intervene in the affairs of another sovereign state. This is not a new issue.

Modern debate traces its roots to the 1931/2 Stimson Doctrine; named for the then US Secretary of State Henry L. Stimson (1867-1950; Sec. of State 1929-33; Sec. of War 1911-14, 1940-45), who joined international denunciation of Japan’s invasion of Manchuria (part of China) and articulated the principle that the US would not recognize territories acquired by force. His argument, based in a key tenet of international law, Ex injuria jus non oritur (Law/right does not arise from injustice), has continued to inform international affairs ever since.[5] But Stimson’s position has not been uniformly supported, despite the UN Charter being read by many international lawyers to mean states are required by law not to recognize annexed territories. Other opinions claim politics, self-interest, and a willful disregard for Human Rights, may as readily guide appeals to non-intervention as intervention, which renders the Stimson Doctrine merely another tool to do a country’s dirty work. What the Stimson Doctrine underlines for us is, however, that identification and recognition of a ‘state’ must reckon with the will or intention that determined and determines its formation, boundaries, ethos, and continuation. The integrity of a state is compromised when the ‘resident’ will of the majority is subject to ‘alien’ pressure and/or when its citizens are denied the freedoms outside intervention legitimately seeks. Meddlesome states that hypocritically appeal to a non-interventionist position (i.e., China) choose to forget that we exist as never before in a symbiotic global community in which (claimed) disengagement can be as dangerous and disruptive as (veiled) engagement. How ironic that US-China relations that birthed the Stimson Doctrine are now embroiled in tacet debate about its contemporary applicability. The world must hope and pray they find a way to reconcile their very different interpretations of the Doctrine’s meaning and significance.

‘What’s in a name?’ the English playwright William Shakespeare (1564-1616) poignantly asks in Romeo and Juliet (1597). ‘What’s in a state?’ we can and should legitimately echo?

Christopher Hancock – Director

[1] N.B. developing usage of ‘state’ (+ ‘estates’) from the Roman philosopher-statesman Cicero’s (106-43BCE) study of the ‘status rei publicae’ (Lit. Condition of public affairs), through medieval application of the term/s to the role or ‘status’ of an individual in society, to later consolidation of the modern meaning of ‘state’ as a political entity by the Italian political theorist Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527) in The Prince (1513/1532), suggest revisiting the core meaning of the term ‘state’ may yield rich fruit.

[2] Cf. In addition to the four ‘states of matter’ (viz. Solid, liquid, gas, plasma), some scientists add to their number (more and less plausibily): Excitonium, electron degenerate matter, neutron degenerate matter, strange matter, Photonic matter, Quantum spin Hall state, Bose-Einstein condensate, Fermionic condensate, superconductivity, superfluid, supersolid, Quantum spin liquid, string net liquid, Dropleton, time crystal, Rydberg polarons, quark gluons plasma, Rydberg matter.

[3] Cf. The German sociologist, historian, jurist and political economist Max Weber’s (1864-1920) oft cited definition of a state, viz. ‘a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory’ (Max Weber: Essays in Sociology [1991], 78).

[4] Political science usually differentiates between a ‘state’ (with a sovereign system of controls over a given region), a ‘nation’ (with political, cultural and historical distinctives), and a ‘government’ (that enables a ‘state’ to control and a ‘nation’ to flourish). With an eye to Africa, Benyamin Neuberger intriguingly conflates these three key terms, maintaining a state is ‘a primordial, essential, and permanent expression of the genius of a specific [nation]’ (cf. ‘State and Nation in African Thought’, Journal of African Studies 4.2 [1977]: 199–205). Commentators often link a state’s weakness to poor military control, a nation’s fragility to an unclear identity, and a government’s impotence to its perceived partiality or ineffectiveness. But stasis in such matters (both in reality and interpretation) are rare!

[5] Cf. The doctrine lay behind, for example, US non-recognition of Soviet annexation and incorporation of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania (cf. The Welles Declaration, 23 July 1940) and subsequently the non-recognition resolution (662/1990) of the UN Security Council after Iraq’s annexation of Kuwait in August 1990.