(Extracted from an ISIS video message, “Strike [Their] Necks – Wilayat al Iraq”, May 2020)

On 21 January 2021, a double suicide bombing in Baghdad claimed the lives of more than thirty people. ISIS claimed responsibility for the attack, their first in Baghdad since 2018 and, as such, a deliberate statement of their resurgence in the region and renewed challenge to the international order in the 21st century. 21 January 2021 was, of course, also Joe Biden’s (b. 1942) first day in office as the 46th President of the United States. ISIS’s timing was intentional.

Following my previous OH ‘Weekly Briefing’ (‘Shifting Sands in the MENA Region a decade on from the Arab Spring’, 3 February 2021), this one examines ISIS’s appeal and assesses the potential impact on the region (and beyond) if ISIS is successful in its bid to reclaim territorial and ideological advantage.

To set our discussion in a brief historical context. The variously named ISIL (Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant), Daesh (its familiar Arabic acronym) and (from 2013) ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) emerged in 2004 from an Iraqi remnant of the radical Sunni jihadist movement, al Qaeda, which Osama bin Ladin (1988-2011), Abdullah Yusuf Azzam (1941-1989) and other Arab fighters in the Soviet-Afghan War (1979-1989) had formed in 1988. Led from 1999 by the Jordanian militant Abu Musab al-Zarqawi (1966-2006), who had run terrorist training camps in Afghanistan, the Iraqi off-shoot of al Qaeda (known originally as Jama’at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad, then as Tanzim-Qaidat al-Jihad fi Bilad al-Rafidayn), engaged in a violent campaign of bombings, hostage beheadings, and suicide attacks during the Iraq War (2003-2011), which it celebrated in grotesque videos and passionate on-line messages. Over time, al-Zarqawi turned the movement from an insurgency against the US military in Iraq into a bitter Shia-Sunni civil war, in the process gaining the infamous soubriquet ‘Sheikh of the slaughterers’ and ‘Emir of Al Qaeda in the Country of Two Rivers’.

Suppressed by the US military presence in Iraq from 2007, ISIS fed off instability in Iraq (and subsequently Syria) and re-emerged after 2011 as a violent, viable, socio-political, religiously motivated, military presence in MENA. In June 2014, the month in which its leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi (1971-2019) proclaimed a ‘Caliphate’ from Aleppo in Syria to Diyala in Eastern Iraq, (the newly named) ‘Islamic State’ launched a ‘Western Iraq’ offensive against Mosul and Tikrit. The US responded with ‘Operation Inherent Resolve’ (August 2014) and over the next year carried out more than 8,000 air attacks on ISIS strongholds in Iraq and Syria (where ISIS had established its capital in the northern city of Raqqa). Terrorist attacks by ISIS affiliates in Egypt (October 2015), Paris (November 2015) and Orlando, Florida (June 2016) stirred a fierce counterattack by Western allies, Syrian Kurds and Arabs. At the height of its power (in, perhaps, May 2015), Islamic State ruled 10m people and had an estimated 28-30,000 ‘foreign fighters’. After sustained pressure from coalition forces, when the newly appointed Iraqi PM Haider al-Abadi (b. 1952) finally claimed victory over Islamic State (9 December 2017), it had lost 95% of its territory, including the flag-ship cities Mosul and Raqqa. By 14 December 2018, when Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) captured Hajin in Eastern Syria, ISIS’s regional control had shrunk to a handful of villages along the Euphrates near the Iraqi border.

(Maya Alleruzzo, c.2019, The Associated Press)

So, what was ISIS’s appeal? To many outside, it seemingly offered little more than military hardship and an early death?

ISIS’s attractiveness to young Muslim men and women was, and is, to many observers both sobering and remarkable. The movement’s call to engage in violent jihad (Lit. Holy war) against infidel Western powers and complicit Islamic allies, drew ‘foreign fighters’ from all over the world. Many came from the MENA region, a sizeable number also came from Europe and N. America; with the largest groups from Tunisia (6,000) and Belgium (5,000), which had the highest % per capita of its population. Looking back there seem to have been three main elements in ISIS’s appeal.

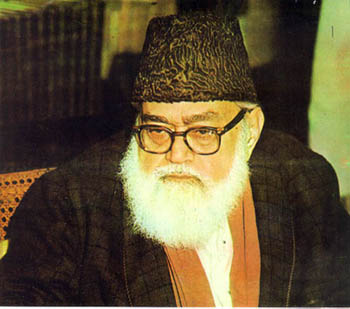

First, a doctrinal re-envisioning of Jihadism. Many ‘foreign fighters’ who were captured and later repatriated spoke of ISIS’s allure, wrapped as it was in a legitimating cloak of evocative Islamic titles and explicit scriptural appeal to the Qur’an, Sunnah and Sirat. Young people educated in – some would say groomed by – salafi groups were targeted by recruiters. In this process, radical movements like the political Hizb-ut Tahrir (fr. 1953), the Sunni missionary Tablighi Jama’at or ‘Society of Preachers’ (fr. 1926), the ‘Muslim Brotherhood’ (formed in 1928 by the Egyptian scholar-teacher Hassan al-Banna [1906-1949]), the ‘ultra-conservative’ Wahabis, and the late-19th century ‘revivalist’ Deobandis, all played a part. To those seeking a vision and life that was ‘pure’ in ethos and expression, ISIS offered an ideology (the so-called Ahl al–Ḥadith, Lit. the people of tradition) sourced from a literalist read of classical Islamic texts and doctrines originating from the 2nd/3rd (Islamic) century, or Abbasid Caliphate (ca. 750-1258 AD). This tradition – mediated through men like the ascetic Islamic jurist and theologian Ahmad Ibn Hanbal (780-855), hadith scholar-jurist Ibn Taymiyya (1263-1328) pious polymath Shah Waliullah Dehlawi (1703-1762), central Arabian reformist thinker Muḥammad ibn‘Abd al-Wahhab (1703-1792), itinerant political activist and Islamic ideologist Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani (1838/9-1897), radical Egyptian theorist and poet Sayyid Qutb (1906-66) and Indian/Pakistani Islamist Abdul A’la Maududi (1903-1979) – envisioned modern jihadism. But ISIS not only proclaimed the spiritual and military ‘obligation’ of jihad (with Paradise promised to martyrs), it prophesied a tangible new reality, a proto-state ‘Caliphate’.

(by Makhzan-e-Tasaweer)

Since the abolition in 1924 of the Ottoman Sunni Caliphate by the secularising reformist Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1881-1938), some Muslims had dreamed of a new Caliphate to reverse, symbolically and spiritually, the ‘humiliation’ Islam had suffered historically at the hands of the ‘infidel’ West. Some saw the creation of Muslim Pakistan in 1947 as a step towards a Muslim superstate and thence a global Caliphate. The Taliban used such imagery during the Afghan wars, when their leader Mullah Omar (1960-2013) appeared on a house balcony in Kandahar wrapped like Mohammad in a cloak, a dramatic symbol of Caliphal legitimacy.

Second, ISIS invoked apocalyptic texts and images. Simply put, joining ISIS in its Sunni jihad was presented to recruits as expediting the ‘end times’ battle of Armageddon. The Iranian expert on politico-religious radicalism Farhad Khosrokhavar (b. 1948) has shown how two events increased eschatological awareness throughout MENA. First, the growth of utopianism in European jihadism, as an ideological escape from the grinding poverty and social degradation of European Muslims in the late-19th and early 20th centuries. In this period, the ‘White Minaret’ prophecy gained traction. Greater Syria (al-Shams) is presented here as the location for the final battle between ‘true’ believers and infidel ‘heretics’. During this grand finale, Jesus (Isa in Muslim tradition) ‘returns’ to Damascus’s ancient White Mosque. This vivid prophecy, which held out the prospect of final victory and end to a life of struggle, retained its potency over time. Indeed, when Belgium farm-labourer convert – and arch-jihadi recruiter – Jean-Louis Denis (NB. sentenced to ten years in prison in 2016 for his activities) sent a dozen of his protégés to Syria, it was with this apocalyptic ‘White Minaret’ prophecy in their ideological rucksacks. This prophecy gained renewed traction, says Khosrokhavar, after the second event; namely, the ‘Six Day War’ (June 1967). Over time, the plight of Arab forces during that conflict, and the chaos that ensued, began to be linked (via the ‘White Minaret’ prophecy) with the Coalition invasion of Iraq (2003) and the ‘Arab Spring’ (2010-2012). As American Arabist David Cook charts in his book Contemporary Muslim Apocalyptic Literature (2008), such ‘end times’ apocalyptic thinking sold strikingly well on Middle Eastern and Asian market stalls.

To be clear: apocalypticism (among other ideological and doctrinal differences) set/s ISIS apart from al Qaeda. In its quest to create a proto-state Caliphate, it engineered conflict at Dabiq, Syria, according to a Hadith attributed to Muhammad the site of Armageddon. So, too, British terrorist Muhammed Emwazi (1988-2015), so-called ‘Jihadi John’, chose to stand outside Dabiq brandishing the head of American aid worker Peter [Adbul-Rahman] Kassig (1988-c. 16 November 2014) to evoke jihadi apocalyptic tradition – and, yes, to signal ISIS’s brutal disregard for the lives of its infidel enemies.

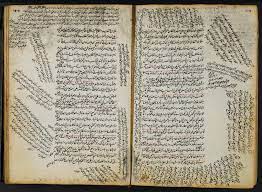

by Sadr Al-Shari’a (d. 1346 AD)

Thirdly, and most uncomfortably, though ISIS’s methods have limited appeal, elements of its core ideology have been embraced by Muslims at large. There has been broad support, for example, for an increased ‘constitutionalisation’ of shari’a (Islamic law and practice). In this process, shari’a is extended from personal and communal guidance to regulated state laws. A 2017 Pew Research survey of 38 predominantly Muslim countries (as well as Russia) showed over 75% of respondents wanted shari’a as their country’s legal system. This is not as surprising as it may seem. For more than a century, the issue of the relation between shari’a and state power has been debated, particularly among Muslims living in democratic, pluralistic countries. It was in part the lack of pre-eminence accorded shari’a in MENA, or the perceived idolatrous fusion of shari’a with other (usually Western) civil law codes, that enflamed jihadist passion and activity long before ISIS. Crucially, to salafis any fusion of shari’a de-legitimises a state. Even in Saudi Arabia, which admits many hudud (Lit. limits or prohibitions, viz. punishments in the Quran and hadith for crimes against God) excluded in other Islamic countries (e.g. Malaysia), shari’a is still deemed insufficiently implemented to fully legitimise the ruling family. The issue isn’t only, though, about the degree to which shari’a is implemented, but which of the four shari’a ‘schools’ (mahaddab) are honoured. In salafiyya tradition, schools other than 9th century Ibn Hanbal are illegitimate. Why? because they do not follow his Koranic literalism and have greater doctrinal distance from their ideological understanding of the teachings of Muhammad.

Yet, despite its ideological and military successes, in March 2019 the last ISIS stronghold fell to the SDF. This is (still) symbolically, militarily, and socio-politically significant. It frames talk of ISIS’s resurrection and assessment of the threat it currently poses. ISIS’s vision of a new Sunni Caliphate has been severely undermined. Militarily, it is incapable of conquering and holding territory as it once did, but it still represents an engaging ideology (for some) and a significant, albeit vastly reduced, terror group worthy of close global monitoring. Furthermore, the ‘franchising’ of ISIS by groups like ‘Boko Haram’ in Nigeria has perpetuated its ideological and military reach, while the terror attacks in France (April and December 2020) and Austria (November 2020) are a reminder that some will still take the bay’at (oath of allegiance) and carry out operations. As Catherine Zimmerman states on the ‘Critical Threats’ website (18 June 2020) ISIS continues to be ‘resilient’.

So, whilst the threat of ISIS remains substantial, it should not be exaggerated. Nor should the recent bombing in Baghdad cause panic. Though ‘resilient’, military defeat sits ill with ISIS’s salafi ideology. Victory signals divine blessing: defeat suggests disfavour – and, with it, popular de-legitimisation. Read in this light, recruitment may suffer, and the movement shrivel. Contrariwise, recovery of ground lost or another 9/11 might reignite old passions and attract new recruits. What’s more, as Chloe Cornish pointed out recently in the Financial Times (online, 22 January 2021), the ‘distraction’ of the pandemic has given ISIS time to re-build and re-organise. Whether they can convert this into effective action, time will tell. More probably, ISIS will be a thorn in the side of MENA – perhaps also of W. Africa and parts of Europe – for some time, eviscerated by internal power struggles and effective monitoring and suppression by security services worldwide. That is not to say jihadism per se will die. No. ISIS’s success confirms the potency of that old viral ideology, which another group with another name may contract again in time. Meanwhile, past failures and present threats – not least, Iran’s ideological independence and the signing of the ‘Abraham Accords’ by Israel, the UEA and the USA (13 August 2020) – suggest talk of ISIS’s resurrection may be premature.

Dr Sean Oliver Dee, Associate