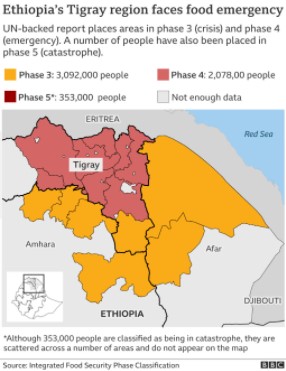

High in the remote mountains of northern Ethiopia a terrible war is waging. Out of sight from a COVID-stricken world and preoccupied media, brutality reigns. The conflict in Tigray, which began in early November 2020, is perhaps the most brutal and secretive anywhere. Initially a fight between Special Forces of the Tigray Regional Government and the Ethiopian National Defence Forces (ENDF) – with the support of Ethiopian Federal and Regional police, and gendarmerie from neighbouring Amhara and Afar – and the neighbouring Eritrean army, combatants have now been drawn in from Somalia and Sudan. There is little doubt about the threat and severity of the situation. The outcome could ruin and transform the region. An estimated 5.2m. Tigrayans are already in desperate need. A very recent United Nations report has ca. 350,000 currently living in famine conditions. Accounts of child soldiers being deployed by the Eritrean military and thousands of women brutally raped – many gang-raped over a prolonged period – are probably (and tragically) true. The word ‘war’ hardly captures the full horror unfolding in Tigray.

At the heart of this conflict is one simple, but in this case intensely complex, question: namely, how do you rule a nation that has many ethnicities? The question is not unique to Ethiopia, but Ethiopia has its own complex history of trying to answer it. And, crucially, in this instance the question is not only for Ethiopia: if it were, it might be soluble. The fact that politics and ethnicity spill over into neighbouring states means what is happening in Tigray has wider, regional consequences. Like an aggressive cancer, war spreads.

Understanding the origins of the present conflict is vital. The expansion of the Ethiopian (or ‘Abyssinian’) state under Emperor Menelik II (1844-1913; r. 1889-1913] saw the country transformed, with the modern state consolidated in 1898 after Ethiopian forces routed Italian troops at the historic Battle of Adwa (1 March 1896). But the shape of the country was transformed during the 1880s by the extension by Menelik of the power of the highland Christian nation over much of the lowlands until the emperor ruled what are today southern and eastern Ethiopia. Almost overnight, Ethiopia went from being a mainly Christian, highland nation into an empire with more than 80 distinct ethnic groups, many of which were Muslim. Historic conflict between Amhara and Tigrayans was now subsumed in a country in which they were a minority. The largest (and mainly Muslim) ethnic group in Ethiopia, the Cushitic Oromo, which still composes ca. 35% of the population (N.B. they are also in Kenya), were deemed inferior. Also designated from the early 15th century as Galla – a term now essentially derogatory – the Oromo (Lit. children of Orma, ‘sons of Men’, or a person or stranger) were habitually enslaved, even after formal abolition of slavery in Ethiopia in the 1940s.

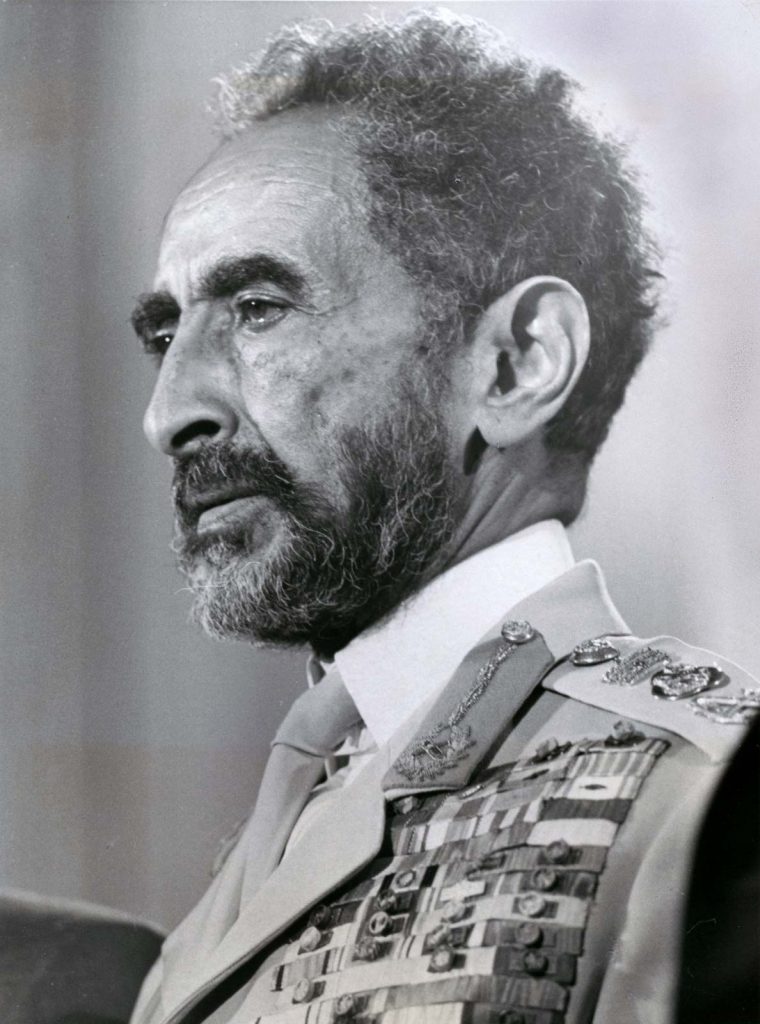

Twentieth century Ethiopia suffered from its 19th legacy. Civil strife was endemic. The Italians, who had invaded again in 1935 as part of Benito Mussolini’s (1883-1945; PM. 1922-1943) expansionist ambitions, were finally expelled by a British led force in 1941. The then Emperor Haile Selassie (1892-1975; r. 1930-1974) – a member of the ancient Solomonic dynasty that traced its roots to the 10th century BC ruler Menelik I – who had first come to prominence in 1916 as Regent Plenipotentiary of Ethiopia, was reinstated. But, in 1961 rebellion erupted in Eritrea, Ethiopia’s gateway to the Red Sea. This conflict rumbled on for thirty years. In 1974 Emperor Haile Selassie – who is now synonymous with modern Ethiopia’s fluctuating fortunes – was overthrown in a military coup, mainly for mismanagement during a famine. The military – or Derg, as they became known – seized power. Crucially, while the rebellion in Eritrea was under way, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) launched their own uprising in northern Ethiopia. Eritrean and Tigrayan forces clashed in the coming years for ideological and tactical reasons, but finally united in what proved to be a successful campaign to seize their respective capitals. On 24 May 1991 Eritrean forces took Asmara, while four days later – in a carefully co-ordinated campaign – Tigrayans troops took the capital Addis Ababa, with support from Eritrean troops and artillery.

For a brief spell peace prevailed. Eritreans ruled their own state (formally independent from 1993) while Tigrayans, in a loose set of ethnic and regional alliances (including with the Oromo) ruled Ethiopia. For a while, although only 7% of the population, the minority TPLF’s system of ‘ethnic federalism’ held strong. But the system was fragile, and the situation gradually deteriorated. A new constitution introduced in 1994 created nine regional states (defined by ethnicity) and two multi-ethnic metropoles. With international backing, the small, but powerful, TPLF, continued to pull the strings by controlling the regional parties behind the scenes. It could not last.

Over time, control the Tigrayans exercised through ‘ethnic federalism’ weakened as regional interests came to the fore. Regional loyalties, promoted by powerful ethnic leaders with paramilitary forces, displaced a sense of Ethiopian national identity with central government in Addis Ababa. Clashes between regions erupted. Ethnic groups sought the return of ancestral lands. Territorial disputes escalated across Ethiopia. By 2018, the Ethiopian populace were tired of Tigrayan minority rule, which they viewed as corrupt, self-serving and unrepresentative. Matters came to a head in early 2018 when demonstrations by Oromo youth led to an ousting of Tigrayan officials and the creation of a new government (2 April 2018) under Oromo Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali (b. 1976), fourth Prime Minister of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia.

The new Prime Minister moved quickly against ‘ethnic federalism’, his aim being to re-centralise control. Since coming to power, he has faced stiff opposition from some of the ethnically differentiated regions the Tigrayans created. Abiy also initiated a reform programme, the most significant being to end the ‘no-war, no-peace’ confrontation with Eritrea, which had continued since a bitter border war of 1998–2000. A visit to the Eritrean capital, Asmara, in July 2018 was reciprocated by a visit to Addis Ababa by the former head of the EPLF, Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki (b. 1946). Prime Minister Abiy was – it now seems precipitously – awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019 for his reform initiatives.

What appeared to be a smooth transfer of power hid deeper issues. On one question the Eritrean President Isaias and Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy were united: the Tigrayans had to be removed. Isaias’s loathing of the Tigrayan leadership went back to disputes in the 1970’s and ‘80’s. He saw them now as impeding his influence over Abiy, whom he considered young and compliant. For Abiy, the Tigrayans embodied the ‘ethnic federalist’ ethic he was determined to purge from a divided nation. Abiy and Isaias drew the Somali leader Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed aka ‘Farmaajo’ (b. 1962; PM 2010-2011; President and Acting Pres. 2017-present) into their scheme. By September 2020 they had had three trilateral meetings. Though never made public, it soon became clear they believed that by uniting their forces they could remove the Tigrayans and re-configure the balance of people and power in the Horn of Africa.

Somali President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed aka Farmaajo (b. 1962)

Briefed by the Ethiopian military and security services that they had previously controlled, the Tigrayans were aware of what was transpiring. In response, they blocked transfers of heavy weapons from the Eritrean border, refused to accept replacement officers for the army’s Northern Command (based in Tigray) and made preparation for the impending clash. In the early hours of 4 November 2020 conflict erupted with fighting in the Northern Command headquarters in the Tigrayan capital, Mekelle. Ethiopian troops and Amhara militia stormed Tigray from the South and East. Almost simultaneously Eritrean and Somali forces attacked from the North. Their first objective was to cut Tigray’s links to neighbouring Sudan, which was a possible conduit for supplies and a safe-haven for refugees. The attacks were successful. On 29 November 2020, the Tigrayan regional capital was encircled and within hours fell. Prime Minister Abiy was triumphant: military operations in the Tigray region were, he boldly tweeted, ‘completed and ceased.’ Events would prove his confidence misplaced.

Over the coming months, the TPLF returned to its roots as a guerrilla organisation. It set up camps in Tigray’s remote mountain region from where it has continued to launch surprise attacks. It will, a spokesperson said, fight on until the ‘invaders’ are expelled. In April 2021, Prime Minister Abiy admitted the war was far from ‘over’, with his forces bogged down in ‘difficult and tiresome’ fighting on no less than eight different fronts. Since then, it has become clear much of the fighting – and many of the atrocities – have been committed by Eritrean troops, many forcibly conscripted by the ageing President Isaias. Some of these conscripts are very young, with little or no military training. Mass killings of civilians in or near Adigrat, Hagere Selam, and in Humera, Mai Kadra, Debre, Aksum and Hitsats refugee camp, have been reported. Details of such are hard to obtain since access to large parts of Tigray has been denied to journalists, but reports by Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have concluded that most of the atrocities were carried out by Ethiopian or Eritrean forces.

While the fighting has continued there has been limited access to large parts of Tigray even for the international aid agencies. Humanitarian organisations complain they cannot reach vast numbers of people who are now on the edge of starvation. The EU and US have introduced limited sanctions against Ethiopia and Eritrea, but these have so far had little impact. The African Union, which has sought to send mediators, was blocked by Prime Minister Abiy, claiming the conflict is an internal issue. The problem for the Premier is that if this conflict drags on it could become entangled in wider regional issues. As noted earlier, Eritrea and Somalia have already been involved, while Eritrean and Ethiopian forces have also clashed with Sudanese forces in a disputed border region, the al-Fashaga triangle. The dam on the Blue Nile that Ethiopia constructed (and proudly termed the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam) is also a contentious issue for Cairo and Khartoum. Egypt (which relies on the Nile for over 95% of its water supplies) fears that the dam will reduce the river’s flow, even though it is only for hydro-electric purposes. Sudan is concerned that any rapid release of water could sweep away farms situated on the Nile’s banks. Egypt and Sudan have conducted joint military operations in the area and made repeated appeals to the international community to prevent the dam from becoming operational until there is a binding treaty governing the dam’s operation. Any of these issues could exacerbate the current situation. For the moment, the war in Tigray appears set to continue. Thousands have already been killed, injured, and raped: now even more face death by starvation as famine and failed relief efforts take hold. The fact we forget wars doesn’t mean they don’t happen, or that people don’t die: they do.

Martin Plaut, Guest Author[1]

[1] Martin Plaut was the BBC World Service Africa News Editor, reporting on the Horn of Africa for over 30 years. Since his retirement he has written several books including ‘Understanding Eritrea: Inside Africa’s Most Repressive State.’ He is currently a Senior Research Fellow, at Kings College, London