The clamor around narrative building can be deafening – and seductive. ‘What do the majority say?’ has a healthy democratic ring to it. But care is needed. We can believe what is wrong. I am reminded of a poignant tale by the Lebanese American author Kahlil Gibran (1883-1931):

Once there ruled in the distant city of Wirani a king who was both mighty and wise. And he was feared for his might and loved for his wisdom. Now, in the heart of that city was a well, whose water was cool and crystalline, from which all the inhabitants drank, even the king and his courtiers; for there was no other well. One night when all were asleep, a witch entered the city, and poured seven drops of strange liquid into the well, and said, ‘From this hour he who drinks this water shall become mad.’ Next morning all the inhabitants, save the king and his lord chamberlain, drank from the well and became mad, even as the witch had foretold. And during that day the people in the narrow streets and in the marketplaces did naught but whisper to one another, ‘The king is mad. Our king and his lord chamberlain have lost their reason. Surely, we cannot be ruled by a mad king. We must dethrone him.’ That evening the king ordered a golden goblet to be filled from the well. And when it was brought to him, he drank deeply, and gave it to his lord chamberlain to drink. And there was great rejoicing in that distant city of Wirani, because its king and its lord chamberlain had regained their reason.

The story of this purportedly ‘wise’ king is both amusing and insightful. It exposes not only the threats and potential vulnerability of a leader, but also the guile and wiles of the people who follow him. Life and leadership, we know all too well, can be extremely complicated.

Like a wise sea captain, good leaders navigate carefully. They assess the ‘mood of the nation’, as a captain the weather. They trim the sails of policy to capture every breath of support and steer carefully by unpopular decisions. They adapt to succeed. Such is politics, the (in)famous ‘art of the possible’, in which a leader is always at risk from surrendering him/herself to another and forsaking ‘the good’ for the ‘mood’ of the nation. And, of course, they are not alone. As individuals, we are also victims of ‘the general mood’, avoiders of the unpopular, gullible readers of dastardly tales. Our ears – like the ‘goblet’ in Gibran’s story – risk being filled with ideas and impressions shaped by others, of believing as ‘truths’ lies forged in another’s kiln. Checking evidence is hard – especially in a world flooded with ‘fake news’, ‘political agendas’ and manipulative media marketing – but that doesn’t absolve us of the responsibility to check, investigate, suspend judgment and keep ‘an open mind’.

Framing a narrative is hard. Some degree of superimposition is inevitable. We are always tempted to ‘look for me in him’ or assume what I count preferable must be true! Perception and projection are near neighbours. Precipitous decisions and blind assumptions can, we know all too well, lead us astray. Hasty conclusions are as dangerous as blind convictions. The narrative we develop about a leader’s worldview needs effective checks and balances.

Let me illustrate. Soon after the brutal October 2020 Islamist attack in Nice, India’s PM Narendra Modi (b. 1950; PM fr. 2014) sent his condolences to French President Emmanuel Macron (b. 1977; Pres. Fr. 2017). India was the first non-Western nation to condemn the attack. The US, UK, Australia, and others were silent (to the dismay of many political and media observers). Senior French officials described India’s response as ‘very meaningful’. If we drill down into PM Modi’s action deeper, unexpected, and noteworthy, issues emerge.

First, though Modi is the self-styled guru, and advocate for, India as a revitalised Hindu nation, he and his BJP party govern a country that is home to 170m. Muslims and has close domestic and economic ties with Saudi Arabia, the Gulf States and the Middle East. Islamist violence is a live, local, political issue for PM Modi and his government. But notice how PM Modi’s message to President Macron was interpreted and presented by the media. A few commentators said it reflected a recent proximation of India and France: witness France’s support for India over Kashmir and terrorism at the UN Security Council, and the special invitation President Macron sent PM Modi to attend the G7 gathering in Biarritz last year. Rather more commentators, however, chose to present PM Modi’s expression of sympathy as a cynical, populist, political ruse to justify (Hindutva) repression at home, and entirely in keeping with his oppressive Citizens Amendment Act (2019). Projection and agenda skew interpretation. If we are not careful, the ‘goblet’ we are served is laced with social poison.

Second, set Modi’s message of condolence in a larger historical context. To a Hindu, India suffered Islamic violence for centuries. For six hundred years, from the destruction and looting of the sacred Somnath [Hindu] temple in Prabhas Patan (W. coast of Gujarat) by the first ruler of the Turkic Ghaznavid dynasty, Mahmud of Ghazni (971-1030; r. 999-1030), through to the sixth Mughal emperor Aurangzeb (1618-1707; r. 1658-1707), Hindus and their holy sites and shrines suffered grievously at the hands of their Islamic neighbours. This still colours perception. History does not justify retaliation, but it is a reminder that India’s narrative of Islamic terrorism is distinctive – and different from that of the west. It is easy to down the ‘8-minute’ article ‘PM Modi hates Muslims’, far harder to swallow the truth that in India 30m. Shia Muslims are among PM Modi’s most devout followers.

Take another example. During the March Covid-19 lockdown, EU President Ursula von de Leyen announced an EU-wide export ban on (some) PPE to safeguard local need. An acute ‘Intelligence Squared’ podcast (www.intelligencesquared.com) asked rhetorically, ‘What if President Donald Trump had made that same announcement?’ Critics of his ‘America First’ stance would have raged. Paradoxically, then, the 2020 presidential election saw a sharp increase in ethnic support for the President. To be sure, media-savvy President Trump has been all too aware that ‘goblets’ of popular perception have both poisoned and refreshed his electoral base. Reading and reporting this complex figure – like every global leader – was, and is, always going to be hard. The risks of projection and misperception abound. Heightened self-awareness in leader and lead may help to minimize the threat this poses international harmony and personal integrity, but risks, it seems, are ever present. We have been reminded in recent ‘Weekly Briefings’ that, thankfully, ancient wisdom holds true.

So, to end, a caution and an encouragement.

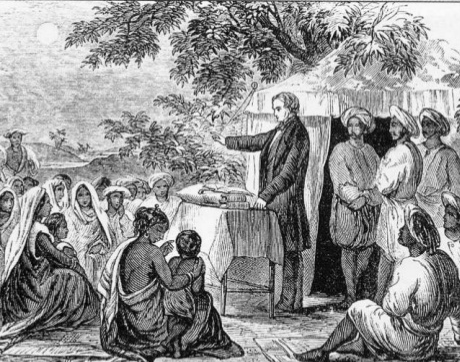

First, the caution. Christian mission brought riches many in India deny and problems many in the West miss. Culture clashes abound. The expectation that East or West will adjust to the other without error or regret is misplaced. Take, the post Enlightenment, empirical (if not Imperial!) Western predisposition to ‘categorize’: the atomic structure of a substance is defined, the language and thought forms of a race are specified, the class, ethnicity and religion of a group are identified. But how ill-fitting such methodology for the Indian sub-continent where ‘caste’ cuts across class, where the Western form of ‘religion’ doesn’t fit ‘Hinduism’ (as a cultural, moral, social and spiritual hybrid) and where identity is a fragile, regional, generational construct borne of two hundred and twenty languages and a five thousand year history. The seemingly simple question posed by missionaries of old and businessman today, ‘What do I call you?’ was, and is, almost impossible to answer! When categorization blurs subtle distinctions it becomes an enemy and not a friend of effective cross-cultural analysis. However, categorization that admits mystery, discovery, and risk may enrich how we read and represent leaders and lead more wisely around the world.

Second, an encouragement. The first Vice-President and second President of India was the gifted philosopher and statesman Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (1888-1975; VP 1952-62; Pres. 1962-67), who was also, incidentally, the first Indian to hold a professorial chair at Oxford University (1936-52). Commenting on the Hindu Upanishads, Radhakrishnan states on one occasion: ‘It is by a strictly personal effort that one can reach the truth.’ This is fascinating. It is an idea as alien to Western views of divine ‘grace’ as it is to Buddhist notions of Karma or Hindu attitudes towards enlightenment (‘Personal effort’ is far too much or far too little to these!). What’s more, to postmodern cultures attuned to ‘easy’ knowledge and engulfed in internet data and social media, where it is quicker to re-tweet another’s ideas than think for oneself, Radhakrishnan elevates the power and potential of our own ‘personal effort’. Elusive ‘truth’ can be found. Complexity can be unraveled. My perception can be changed. Bolting food is bad for you, quaffing a ‘goblet’ of uncritical opinion equally so. Wiser, surely, to check what we are eating and drinking lest the health of our minds be poisoned like that of Gilbran’s king and misguided people. Singular stories build momentum. Diversity is often painful, but a healthy diet is always a balanced mixture of ingredients.

When the captain of a mighty oil tanker (cruising at ca. 20 knots) decides to stop, it’s said it can take more than 2 miles to halt the vessel. ‘Emergency stops’ are impossible! The engine is turned off 15 miles before docking! Changing opinions is difficult. The ‘mood of a nation’, like the ‘climate of opinion’ or a ‘prevailing view’, is not easily changed. Better to attempt the hard task of change than letting tankers of error pile into our fragile global harmony.

Rahil Patel, Associate