Scholars – and not a few wits – have debated for decades the definition (and importance) of a literary ‘classic’. In a 1900 lecture, ‘Disappearance of Literature’, the American author Mark Twain (1835-1900), who was always ready with an incisive quip, quoted a contemporary academic’s view that a classic is ‘something that everybody wants to have read and nobody wants to read’! As acute is the English playwright and ‘realist’ author Alan Bennett (b. 1934): ‘Definition of a classic: a book everyone is assumed to have read and often thinks they have read themselves.’ Humour, as we know, can make points sobriety avoids. Important things can, and must, sometimes be said directly: the doctor gives her blunt diagnosis, the accountant cites the balance sheet, the crew reports damage to the hull. But truth, like wisdom and love, is often as effectively conveyed indirectly; through a compelling image, with an evocative story, in a belly-shaking joke. Hard truths ingested by Mary Poppins’s delightful ‘spoonful of sugar’. After all, even Jesus commends godly guile (Matthew 10.16)!

Irish author – and erstwhile busker and apothecary’s assistant – Oliver Goldsmith’s (1728-74) play She Stoops to Conquer (1st perf. 15 March 1773), with its suggestive subtitle ‘Mistakes of a Night’, is both humorous and a ‘classic’. It also makes an important point in an indirect way. If we accept Columbia University professor Mark Van Doren’s (1894-1972), perhaps overly inclusive, definition of a ‘classic’ as ‘any book that stays in print’, Goldsmith’s play is certainly a candidate. Performed on stages across the English-speaking world in the 19th and 20th centuries (most notably, with actors Lionel Brough [1836-1909] and Lillie Langtry [1853-1929] in the 1860s and 1880s, and at the Garrick Theatre, London [1969] and in Sir Peter Hall’s 1993 version), made into films (1914, 1923) and famously set for television in 1971 (with Sir Ralph Richardson, Tom Courtenay and Juliet Mills), She Stoops to Conquer has like other ‘classics’ transcended time and culture to reach and teach audiences young and old. Few English literature students in the UK have eluded its grasp. The 1971 BBC production joined twelve others as ‘Classic Theatre’, which the US National Endowment for the Humanities funded for use in thousands of American schools. Here is high quality literature and humour meeting educational needs and communicating timeless truths. It has, as American poet Ezra Pound (1885-1972) said of a ‘classic’ in his ABC of Reading (1934), ‘a certain eternal and irrepressible freshness’; or, as Italo Calvino (1923-85) puts it in Why Read the Classics? (1991), ‘it has never finished saying what it has to say’.

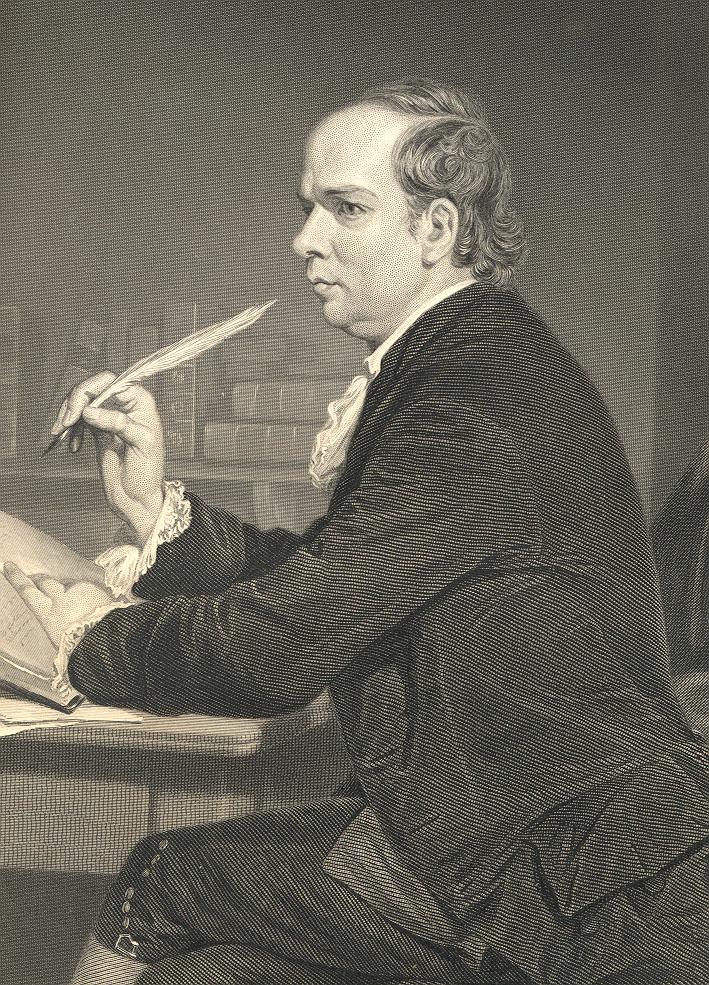

So, what does Goldsmith say, and how does he say it? Otherwise best known for his poignant novel The Vicar of Wakefield (1766) and searing caricature of a ‘Chinaman’ in The Citizen of the World (1762), Goldsmith’s She Stoops to Conquer set out to be funny. To his friend, the diarist Dr Samuel Johnson (1709-1784), the play was not a traditional ‘sentimental (viz. gently serious) comedy’, it rejuvenated so-called ‘laughing comedy’, like Richard Sheridan’s (1751-1816) plays The Rivals (1775) and The School for Scandal (1777). As Johnson’s gloomy secretary James Boswell (1740-95) quotes him as saying: ‘I know of no comedy for many years that has so much exhilarated an audience that it has answered so much the great end of comedy – making an audience merry.’ Here is laughter for laughter’s sake, humour for the sake of being funny. The late-18th century needed this wholesome therapy as much as the early 21st century. Our world may not be the flat Cambridgeshire Fens near Wisbech, where She Stoops to Conquer is set, nor our relations as brash, lecherous, scheming, mischievous, manipulative, or quirky as Goldsmith’s characters Charles Marlow, Tony Lumpkin, George Hastings, Constance Neville, Mr and Mrs Hardcastle and their daughter (who ‘stoops to conquer’) Kate, but we live as a singular persona amid other unique characters whose lives we can enrich with laughter or scourge with bitterness. But this is not Goldsmith’s point.

To critics, She Stoops to Conquer is a ‘comedy of manners’: it pokes and prods popular mores to highlight their lunacy and expose hypocrisy and inconsistency in their practice. Class, accent, clothing, money, aspiration and connections all come in for surgical scrutiny in Goldsmith’s play, set over one night within an amusing array of deliberate and accidental ‘mistakes’ of societal convention. All ends well when the young couples (George Hastings-Constance Neville; Charles Marlow-Kate Hardcastle) pledge to wed, but risks and ruses aplenty precede this happy outcome. Perceptions of social superiority should not, to Goldsmith, be given the respect we accord them: that is his point. So, Kate Hardcastle’s ploy (‘stoop’) to secure (‘conquer’) the affections of the mercurial Charles Marlow by passing herself off as a barmaid makes a mockery of the elegance and decorum her family hold dear. Such a ‘conquest’ is not worthy of the name: it is ‘a mistake of the night’. And there is a sharp, two-edged, rhetorical thrust to Goldsmith’s engaging comedy that has struck audiences and readers for 250 years: namely, how worthy are the conventions we hold dear? And how far will we go (in surrendering them and manipulating people) to attain our goals? We may laugh, but not all guile is godly and not all politics or diplomacy worthy.

The title of the play She Stoops to Conquer is worth pondering in conclusion. First, evidence suggests Goldsmith struggled to decide what to call his new play. On the ninth night of Arthur Murphy’s (1727-1805) play Alzuma (13 March 1773), Covent Garden Theatre’s playbill announced: ‘On Monday, (Never Performed) a New Comedy call’d The Mistakes of a Night.’ Before its first performance, Goldsmith had opted for the title She Stoops to Conquer; a phrase found on the lips of Kate Hardcastle in one version of the text: ‘I’ll still preserve the Character in which I conquer’d [1st ed. ‘stoop’d to conquer’].’ However, as literary critics point out, behind this lies an adapted, or corrupted, quotation from poet John Dryden’s (1631-1700) Amphitryon III, ‘The prostrate lion, when he lowest lies, / But kneels to conquer, and but stoops to rise’ (orig. ‘The offending lover, when he lowest lies, / Submits, to conquer; and but Kneels to rise’). Why on earth is this important; let alone interesting?! Because Goldsmith had been clearly captured by an idea – ‘stooping’ or submitting as a pathway to power and victory – and did not want to lose it. It is a good and worthy idea, too; although not one, we might imagine, on the front page of (re-) Election Manifestos or ‘Good Management’ manuals. Interestingly, a 2009 Harvard Business Review article by Jim Collins, entitled ‘Level 5 Leadership: The Triumph of Humility and Fierce Resolve’ (https://web.archive.org/web/20091229150239/http://www.hr-newcorp.com/articles/Level5%20Leadership_Jim%20Collins.pdf: accessed 28 October 2020) disagrees. Controlled self-abasement (like Kate Hardcastle) has, the article argues, demonstrable power in corporate affairs. It makes sense: the brash breed enemies, the lowly build respect and teams. Who ‘stoops to conquer’ anymore? The wise and effective leader, it seems. Ancient wisdom concurs: ‘Humility comes before honour’ (Proverbs 15.33, 18.12).

Second, the title She Stoops to Conquer is a fine reminder of the inherent power of the ‘classic’ virtue of ‘humility’ (Lat. humus; lit. ground, soil) found in all the major religions of the world. ‘Virtues’ and ‘classics’ share a common identity. They are both ‘classical’, as Charles Sainte-Beuve (1804-69) wrote in his famous 1850 essay ‘What is a Classic?’, ‘not because they are old, but because they are powerful, fresh and healthy’. In other words, just as age has not withered the play, She Stoops to Conquer, neither can age shrivel the value and power of virtue/s. Though Buddhism, Judaism, Christianity, Islam (lit. from the root S-L-M, surrender or humility), Sikhism and Daoism all interpret humility slightly differently, in each we find a consistent sense that ‘self’ is rightly displaced to a subordinate (not necessarily demeaning) role by God, another, the Spirit and the (spiritual) ‘Law’. This act of conscious subordination assists management of inclinations that interfere with good ends and God-inspired actions. It is not surprising the humble ‘conquer’: they have, in religious terms, faced and fought the greatest foe, themselves. Of course, as Goldsmith’s play makes clear, guile may have a soft (and amusing!) self-interested face, that doesn’t mean it cannot also have a granite disposition to aspire to the highest ideals and thence attain with humility the highest offices.

But, let me give the last word on this to the English scholar and writer C. S. Lewis (1898-1963), who writes in his own ‘classic’ Mere Christianity (1952):

Do not imagine that if you meet a really humble man he will be what most people call ‘humble’ nowadays: he will not be a sort of greasy, smarmy person, who is always telling you that, of course, he is nobody. Probably all you will think about him is that he seemed a cheerful, intelligent chap who took a real interest in what you said to him. If you do dislike him it will be because you feel a little envious of anyone who seems to enjoy life so easily. He will not be thinking about humility: he will not be thinking about himself at all.

Christopher Hancock, Director