(Xinhua News Agency)

On Thursday 10 November 2021, in a closed-door meeting of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), 370 senior officials re-appointed President Xi Jinping (b. 1953; Pres. 2014-present) for an historic third term and enshrined him formally as an era-defining figure of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) alongside Mao Zedong (1893-1976), the nation’s founder, and Deng Xiaoping (1904-1997), chief architect of China’s ‘Period of Reform and Opening’ (from 1978) or, as it is now called its ‘Great Transformation’. In a series of articles (beginning on 1 November 2021), The People’s Daily hailed Xi as a ‘Marxist politician, thinker, [and] strategist’ with ‘immense political courage, intense sense of historical accountability and deep love of the people’. A man who embodied the party’s ideal of ‘not fearing a strong enemy, not fearing risks’ and ‘daring to fight and win’. What’s really going on here? Is Xi wanting to avoid being outshone by his erstwhile ‘best friend’ across the border, Vladimir Putin (b. 1952; Pres. 1999-2000, 2000-2008, 2012-present)? Perhaps.

In many ways this rebranding of Xi is appropriate, given his already cult like status, his unchallenged autocratic rule, his rejuvenation of the power and prestige of the CCP, and the unswerving loyalty he claims to have from China’s vast population. The move has left pundits and politicians in the West asking, however, whether Xi’s Maoist style is a return to China’s revolutionary ideological roots, or something new.

As in the Mao era, China is at odds with much of the political, legal, and economic system (and personnel) in the West. President Xi’s failure to attend COP26 outraged many. But, below the surface of the revival of political enthusiasm for ‘new era’ China’s revolutionary roots, Xi seems to be steering China in a decisively new direction. On closer examination, this is inspired less by Maoist ideology and more by the writings of the nowadays little-known German lawyer and political theorist, Carl Schmitt (1885-1985). Lauded by the Princeton political theorist Jan-Werner Müller (b. 1970) as ‘liberalism’s most brilliant enemy’ and ‘Crown Jurist of the Third Reich’, Schmitt isn’t everyone’s hero – except, it seems, Xi Jinping and the new cognoscenti in Beijing.

You will find few references to Mao, Lenin and Marx in the official rhetoric that surrounds President Xi: you will find numerous direct references and allusions to Carl Schmitt. Schmitt’s appeal, for Xi and his Beijing allies, lies in his critique of (what he sees as) the endemic political and legal weaknesses inherent in a Liberal Democracy. Schmitt argues for an alternative system of government – in line with what he calls ‘the true grain of human governance’ – which fuses totalitarian dictatorship, constitutional order, and a government-controlled legal system. In this conceptual and practical fusion, China’s political and intellectual elite today find material to support their view that this is the key to China’s unique form of government and its shining path to prosperity and hegemony.

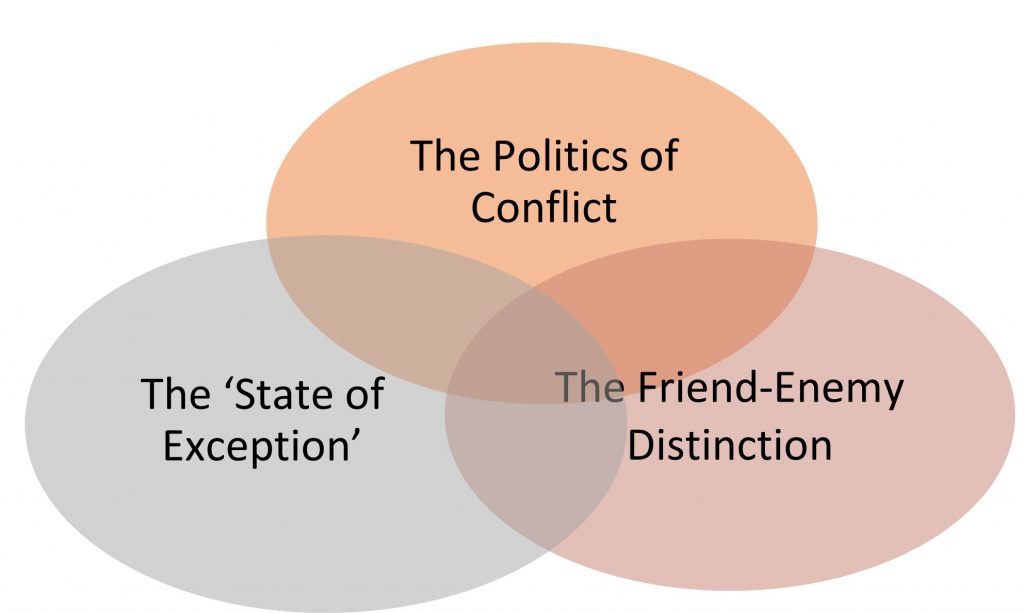

Schmitt’s theory of law and government is rooted in a convergent ‘trinity’ of principles, [1] which he identifies as the politics of conflict, the ‘state of exception’ and ‘the friend-enemy distinction’ (see below). These principles recur throughout his writings.

To Schmitt, politics is forged by conflict and the need for survival. For him, order does not precede conflict, it flows from it. Humans seek common bonds, corporate identity, and an agreed order to survive and flourish. In time, social bonding, identity, and order evolve into codified systems of law and government with a primary purpose to secure national survival. In a national crisis, a ‘state of exception’ occurs in which law is legitimately set aside until order is restored. In a ‘state of exception’ a Sovereign has the right to define friends and enemies to defend one and destroy the other. In such a situation, law becomes intrusive and irrelevant. As Schmitt states, ‘[T]there exists no norm that is applicable to chaos. For a legal order to make sense a normal situation must exist, and he is sovereign who definitively decides whether this normal situation exists … Sovereign is he who decides on the exception.’[2] When the storm abates, law returns. That’s the promise.

Schmitt’s logic has gained traction in China under Xi. The West is represented there as weak because of its deference to due process and judicial review. Checks and balances are seen as rendering a Sovereign feeble in a crisis. Due process hides and shields them in shameful ways.

It is not difficult to see a practical application of Schmitt’s ‘state of exception’ in the way Xi has led China’s response to Covid 19, to confronting the Uyghur Muslim minority in Xinjiang (recasting their ‘identity’ as a terror threat), and to countering the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong (defining it as ‘splittism’[3] and insurrection). In each case, legality is subordinate to a perceived national emergency. Xi is cast as the sovereign defender of the State and of its uniquely Chinese form of Constitutional Democracy. When the crisis is past there will no longer be a need to act in this way. Meanwhile, China can protect her citizens and prosperity without the encumbrance of the judicialization that belabours Western nations.

But a question remains. Are appeals to Schmitt by Statist scholars merely obsequious window-dressing or do they reveal the ideological heart of Xi’s new vision for China? The widely reported crackdown and incarceration of Uyghur Muslims in the Western Province of Xinjiang, and imprisonment of pro-democracy activists in HK, provide clues.

Leaked documents from Xinjiang reveal that the treatment of the Uyghurs can be directly traced to President Xi or, at the least, to officials in his inner circle. As the award-winning documentary journalist James Milward has argued, China’s policy to incarcerate more than a million Uyghurs is unprecedented. He writes,

[T]his punishment … based on less than a handful of terrorist events is unprecedented even for China and meant setting aside of even the nominal formal Constitutional guarantees of freedom of Religion and religious practice by Muslims in China. The only comparable act would have been the Cultural Revolution when all religion was banned, but this is different in that it is targeted on a specific people and their religious practice. (Milward interview)

In light of Schmitt, Xi’s action was, as Milward presents it (and President Xi himself argued), legitimate in a ‘state of exception’. Constitutional guarantees could be – and were – set aside because of an imminent threat to China’s geographical and political integrity.

(Wikimedia Commons)

A change in approach can be seen here. Historically, China’s leaders have portrayed issues like Uyghur unrest (and other expressions of regional and ideological ‘splittism’) in terms of economics and societal progress. Xi’s speeches inside China on the Uyghur issue have struck a very different note. He has spoken of the ineffectiveness of material measures, and the need for collective punishment of a dissident community as ‘the enemy within’. The implications are clear: mass arrest, incarceration, re-education, deradicalization camps, and a raft of measures to effectively obliterate the alterity of Uyghur ethnicity. Uyghur culture, dress, appearance, language, and Islamic faith, have all been proscribed.

Xi’s response to the Uyghurs has echoes of another, even darker, theme in Schmitt: the need for national homogeneity. The elimination of alterity in China today is evident in recent changes to official terms for ‘ethnic minorities’. Hitherto, China’s fifty-five ‘ethnic minorities’ were classified as shaoshu minzu 少數民族 (Lit. minority nation) or zhonguo gezu renmin 中国各族人民 (Lit. Chinese people of different nationalities). The official term for minority people is now zhonghua minzu (中华民族) or ‘Chinafied people’. This reflects China’s broader policy of ‘sinification’ and Schmitt’s socio-political emphasis on national homogeneity. The religious and ethnic cleansing of the Muslim Uyghurs, that international analysis has identified in Xinjiang, is not an arbitrary act of despotic power: it is a deliberate expression of Xi’s new ideologically and racially cleansed China. Or, as Schmitt argued: ‘Every actual democracy rests on the principle that not only are equals equal but unequals will not be treated equally. Democracy requires, therefore, first homogeneity and second—if the need arises—elimination or eradication of heterogeneity.’[4] Schmitt’s ‘trinity’ is etched into Xi’s response to the Uyghurs of Xinjiang.

A further instance of Schmitt’s influence can be seen in Beijing’s response to the pro-democracy protest in Hong Kong. At the height of the crisis, Jiang Shigong (b. 1967), a law professor at Peking University and leading translator of Schmitt’s work, was sent to check ‘loyal’ Hong Kong Officials enacted the controversial new National Security Law (Article 23) passed on 30 June 2020. Following Schmitt, Jiang, a ‘conservative socialist’ devotee of Xi, warned officials that without this new law, HK (and PRC) would face a ‘life or death scenario’, an expression beloved of Schmitt. Without the law, he argued, they were unable to ‘distinguish friends from enemies’ and would render HK an insecure bastion of dissidence, confrontation, violence, and foreign meddling. Beijing would not permit this.

Jiang was not alone in invoking Schmitt. At the time, Chen Duanhuang, another Statist legal scholar, described the situation in HK as a ‘state of exception’ Following Schmitt, he argued that setting aside ‘One Country Two Systems’ was justified to restore peace and stability to HK and avert a national crisis. Following Schmitt, Chen interpreted Beijing’s intervention as the pragmatic prioritising of ‘one country’ over ‘two systems’. HKSAR had to be suspended pending restoration of a right relationship between ‘the Nation’ and HK: only then could HK’s law and courts be restored. For Xi and his apologists, a preference for Schmittian government efficiency, clarity and power is clear. The Sovereign has a right – no, an obligation – to invoke a ‘state of exception’, to set aside law, to distinguish friend and foe, to suppress dissent and manage the process himself until safety and security are restored. This is the driving idea behind Xi’s new vision of government. So, opponents are crushed, the press silenced, youth and dissidents ‘re-educated’, loyalty demanded; and all in the name of national strength and a prosperous imperial future.

The writing and example of Carl Schmitt are more than window dressing in Xi’s China. They underpin the practical legal and political structure of the regime. They fuel patriotic passion and justify presidential actions. They explain China’s internal political behaviour and its international bullishness. They inspire the threat she poses the rest of the world.

A few final points to conclude.

First, the recent re-invocation of ‘Cold War’ rhetoric by Western powers when speaking of China is mistaken. The issue is not a clash of Maoist-Marxism v. Liberal Democracy, nor totalitarianism v. a ‘free market economy’, but of Carl Schmitt v. a Hobbes, Rousseau, Smith and Lincoln. It is a battle of practical ideas and real politik. Schmitt is China’s path from restrictive Communism to fluid Imperialism and Chinese Capitalism. He is no friend of personal freedoms and blanket appeals to ‘human rights’. But, we must ask, what kind of world would we have if Schmitt’s ‘state of exception’ could be invoked when and wherever courts were deemed politically inconvenient and ‘enemies of the state’ were easily defined and swiftly detained? Orderly, may be, but oppressive and inhumane.

Second, Schmitt’s legal philosophy is yet to be fully tested and applied in China. The direction of travel is clear – as many international legal experts have already recognised. Of course, overuse of the term ‘state of exception’ (already?) by Beijing risks invalidating the claim that the crisis is an exception. But international markets thrive on stability and security, on sound constitutions and the application of the ‘rule of law’, on controlling corruption and safeguarding investment. Schmitt’s legal mind jars with economists.

Third, China-watchers fear the present appeal to a ‘state of exception’ may become a long-term justification for repression callously validated by appeal to China as an exceptional State. The risk of losing public trust and legal stability is real, with serious economic and diplomatic side-effects. Under Schmitt, short-term benefits can become long-term debts.

Last, though rarely registered externally, Schmitt has given Xi and the PRC leadership an intellectual frame of reference. It is no surprise Xi has extrapolated from Schmitt nine taboo topics for scholars and public discussion: these include talk of ‘universal values’, ‘civil society’, ‘independence of the judiciary’ and ‘errors of the Party’. Though this restraint is regrettable, it reminds us of China’s ancient tradition of scholar leadership and honouring ideas. While this tradition lives, so does freedom, questioning and change. Despite monitoring. there is still a lively academic culture in China: it will find much in Schmitt to chew on … and, I hope, spew out. Beijing beware!

Tom Harvey, Associate

[1] The iconic image of a ‘trinity’ fits the distinctions yet mutuality inherent in Schmitt’s three categories.

[2] Schmitt, Carl. Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty. Trans. G. Schwab. (Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press, [1985] 2005), p. 13.

[3] A classic Communist term for political separatism and dissent.

[4] Schmitt, Carl. The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy. Translated by Ellen Kennedy. (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. 1985.) p. 9.